A Big Spirit

Some fragmented thoughts on a journey to Ecuador, an encounter with an Indigenous shaman, and a flashback to a fundamentalist me

Thursday, February 2

Grand Rapids, Mich.

My Spanish, dear reader, has always been no bueno. I took just a year of it in high school, and with heartfelt apologies to Señora Fraser, who was very entusiasta, I don’t remember much. (I googled “enthusiastic in Spanish.”) As a teenager in Miami, I did pick up a few very important words and phrases outside the classroom—pastelitos de guayaba y queso, arroz con pollo, yuca frita, lechón. But beyond that? No mucho.

In May, Travel+Leisure sent me on assignment to Ecuador—specifically, to write about a new, lovely, mercifully small cruise ship called the Kontiki Wayra. (Sorry, the story is not online yet, but you can find it in the print magazine’s February issue, which is on newsstands now.)

If you are conversant in the Spanglish that’s commonly spoken in Miami, you might say, “Ay, que nice!” My job isn’t terrible. Except that I am the last person I would ever assign to review a cruise, especially one that boasts about its jet skis (I don’t ride them); its diving and snorkeling excursions (I’m not a great swimmer); and its giant inflatable waterslide (nope).

When the cruise director nagged me about going down that waterslide, I told him, “Absolutely not.”

“It’s fun!” he said.

“No,” I said.

“Nobody has ever said no,” he said. “It’s fun.”

Later, at dinner, when another passenger asked me about the incident, I explained, “I’m opposed to mandatory fun.”

It’s a miracle that anyone sat next to me at a meal after that.

Those of us who have worked as religion reporters will occasionally say that every story can be a religion story. Every story can in some way be a religion story because, tucked within nearly every narrative, one can find some attempt to seek significance beyond humanity, to search beyond our quotidian existence, to sustain ourselves with something beyond our daily bread (or rice or cassava). Whether it’s a story about partisan politics or a profile of a newsmaker or an analysis of some international conflagration, almost always, one can find a religious thread. Humans are meaning-makers. Since time immemorial, we’ve tried to make sense of a world that so often seems nonsensical.

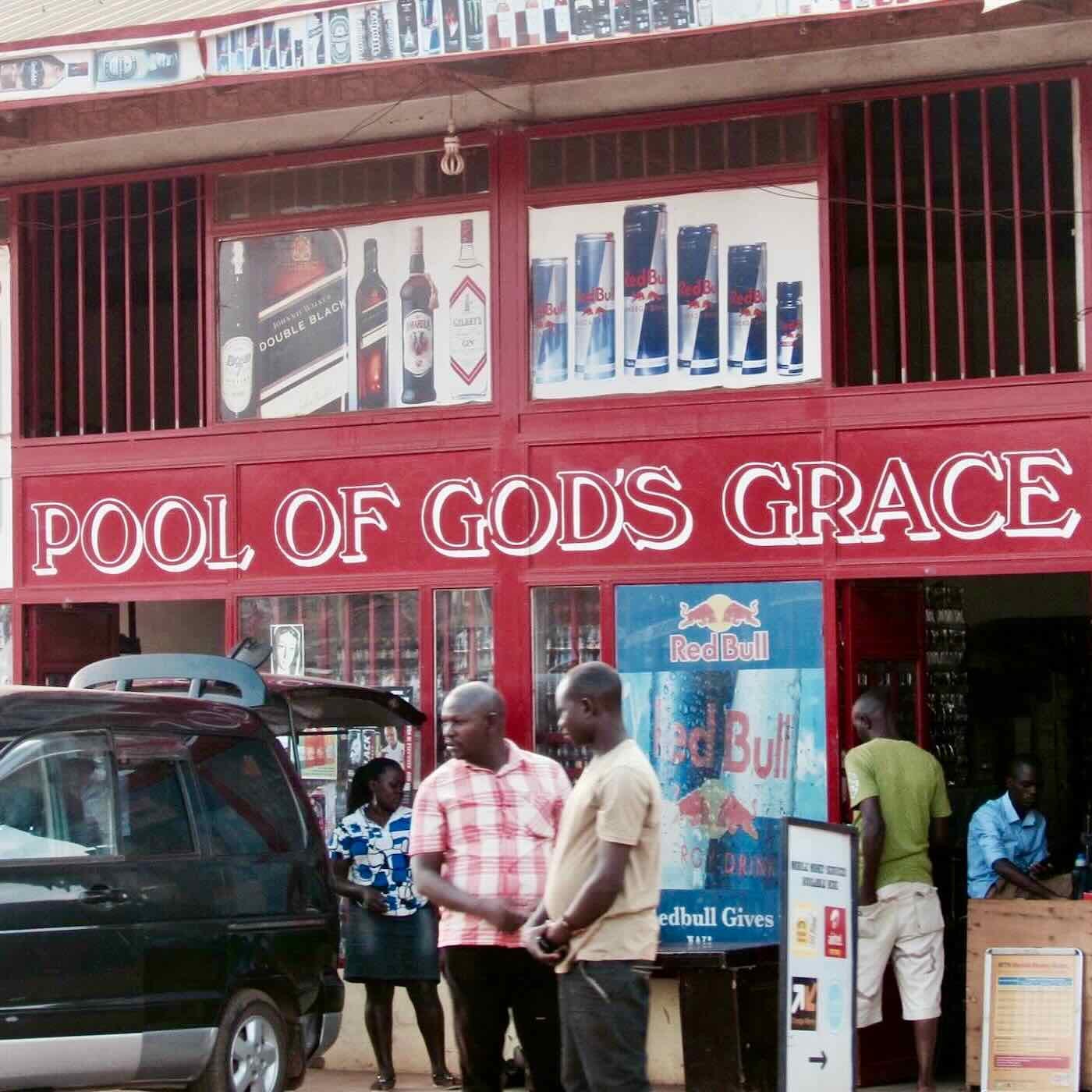

Most of my journalism is travel writing nowadays, and even on these trips, evidence of spirituality surfaces everywhere. Churches and cathedrals are unavoidable if you visit Europe. Eat in a Chinese restaurant—not just in Asia but also in Chinatowns around the world—and you’ll often see altars tucked in the back corners of restaurants and shops. Across sub-Saharan Africa, confessions of faith festoon minibuses and shops; my favorite was a liquor store in Kampala, Uganda, called Pool of God’s Grace.

As much as I believe in the ubiquity of spirituality, though, I still sometimes forget.

One day in Ecuador, we visited a village called Agua Blanca, which is home to a few dozen families descended from ancient Indigenous peoples known as the Manteño-Huancavilca. Agua Blanca is best known for its hot springs, but we were told that we wouldn’t have time to take a dip, because a surprise had been planned.

After a short hike through the woods, we came to a clearing shaded by a grand, sprawling ficus. We were told that we’d been invited into an experience never before shared with outsiders: a ceremony of prayer and blessing led by the village’s head shaman, Plinio Merchán.

Merchán, who wore a grass skirt and a headband featuring the feathers of a grey-backed hawk and whose body was painted with achiote ink, had set up a small altar in the center of the clearing. In the surrounding dirt, he had drawn lines with sawdust to make something of a labyrinth. As he instructed the men to enter the labyrinth through one portal and the women to enter through another, I wasn’t sure what to do. I was a bit curious, yes, but more than anything, I felt fear.

There are moments as reporters when one’s personal histories flare up—we are human, after all. That’s why I don’t believe that any reporter can be objective. We can be fair, but never objective. Our own baggage, our own values, our own biases—these all shape how we experience any event, absorb any happening, receive any story.

In that moment, I suddenly felt the return of Evangelical Jeff—some version of the adolescent me, some devout and pious thing who feared doing wrong. I wondered: Would it be unfaithful to participate? To whom were we even praying? I shudder even as I confess this to you—I am a little bit ashamed!—but I really did think: What would Jesus do?

After a few conflicted moments and no small amount of self-directed incredulity—WWJD? Seriously, Jeff?!—I decided that I was not Jesus, I was here to do a job, and I was not out to prove my piety. I told myself that the most faithful thing I could do was to honor our hosts by participating. So I trailed the others into the labyrinth, accepted the candle and the stick of palo-santo wood that Merchán handed me, and set about taking notes.

Merchán offered his prayers and blessings in Spanish. He greeted the four winds in turn—the east, then the south, then the west, then the north, offering blessings to all in each direction. When he greeted the Fourth Wind, for instance, he hailed “the towns of the north, the cold regions, the countries of the snow, the sons of the white corn. The summer. The youth with their enthusiasm and conscience.” Then he knelt to pay his respects to the fifth direction—the earth—before rising again to hail the sixth—the sky: “Father Sun! Grandmother Moon! To those who have departed already and left us our inheritances! To our fathers and grandfathers, our teachers and heroes! May our prayers meet the heart of hearts and may the light of the universe always warm us!” Then he offered his greetings to the seventh direction—“the point where all the winds cross.”

We had been instructed to echo Merchán after each greeting. The men were to say, “Aho!” The women, “Aha!” This was his version, I suppose, of an amen. But one of my fellow travelers kept saying, “Ahoy!”, like some wayward pirate.

As the shaman’s litany neared its end, Merchán extended his hands toward us in benediction, and he turned slowly around the circle: “From my heart, I salute you all and ask blessings on your families, your friendships, your towns, your nations. May there be peace on earth.”

Merchán kept praying as he wielded a bouquet of West Indian milkberry leaves, dousing us with holy water. But our guides, who had been translating, seemed to lose interest in the words. I tried my best to listen, tried my best to summon Señora Fraser’s lessons—and I swear I heard a familiar phrase:

Padre, Hijo, y Espíritu Santo.

The sudden appearance of the Holy Trinity surprised me, and immediately, I wondered whether I had misheard. I repeated them to myself. After all, I had gone to a Christian school.

Padre, Hijo, y Espíritu Santo.

After the ceremony ended with the sounding of a conch shell, I went up to Merchán, with one of the guides to help me translate. “Did you really say Father, Son, and Holy Spirit?” I asked. “I thought I heard that, but my Spanish is bad.”

He smiled.

“We are all Catholics here,” he replied. “That’s the heritage the Spanish brought us. That’s our heritage too.”

He said that he saw no conflict between his Christian faith and his community’s traditional beliefs. Besides, his people have long learned from and integrated aspects of others’ faiths. In ancient times, the Manteño-Huancavilca boarded balsa-and-bamboo rafts and sailed up and down the Pacific coast, trading with peoples as far north as what is now Mexico. Merchán believes that some of the rituals still practiced in Agua Blanca have Indigenous Mexican roots. “Maya? Aztec? I don’t know.” It didn’t particularly matter to him: “I believe in one God, but that God is represented in many ways in creation.” When he regards the energy in fire, for instance, he sees the power of the Holy Spirit. “The Holy Spirit,” he said, “is a big spirit, no?”

As we left Agua Blanca, I kept turning one of Merchán’s final blessings over in my heart and mind: “May peace settle in all our hearts and spill over to all others.”

Perhaps the heartfelt peace that he spoke of includes the willingness to find evidence of God’s story in a forest clearing far from home. Perhaps it can open us to others’ ways of sharing God’s inclusion and love. Perhaps it can summon the warmth of a spirit-filled fire. Perhaps it can turn us toward grace so abundant that it can cover even the shame and the shards of our past selves. Perhaps it can stir us to embrace the surprising gifts of an unexpected blessing.

Perhaps it’s the opportunity simply to say, “Perhaps.”

Where have you been surprised by grace or met by unexpected blessing? And how’s your Spanish? I’d love to know.

Next week, I will be in Athens, Georgia, visiting the University of Georgia’s Presbyterian Student Center. I will be preaching on I Corinthians 12:12-13:13 (yeah, it’s a lot) at the PSC’s Tuesday-evening worship service. All are welcome. I’d be delighted to see you there! All the relevant information can be found here.

Then, on Sunday, I’ll be preaching at my beloved Crosspointe Church in Cary, N.C. Because I somehow never make things easy on myself, my text for that day will be Hebrews 10:23-11:1. Join us, either in person or online, at 10 a.m. ET.

That’s all I’ve got for this week. As always, I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

With gratitude,

Jeff

p.s. If you want to read more about the Ecuador trip, I wrote last May about chef Rodrigo Pacheco and the best meal I had on that journey.

Where William James left off, Jeff Chu resumes.

I like this a lot.