A Contradiction of Sandpipers

Some fragmented thoughts on smoky skies, degraded ecosystems, the resurrection of Tulare Lake, cooking for a friend, and reflections on a pilgrimage

Thursday, June 29

Grand Rapids, Mich.

Drenching, much-needed storms arrived at our house over the weekend, complete with rolling thunder. I don’t recall ever experiencing rolling thunder before; I thought it was just an overly dramatic word picture (“I see the stars, I hear the rolling thunder...”) in the hymn “How Great Thou Art.” But there it was, like the sustained rumble of kettle drums from the sky—so weird that folks in our neighborhood Facebook group posted questions about what was making that noise.

Then, on Tuesday, the skies over West Michigan turned thick and gray. From inside our house, it seemed like just another foggy summer morning. But the second we stepped outside for Fozzie’s morning constitutional, we could smell the difference: Shifting winds in the wake of the thunderstorms had brought smoke from the wildfires in Quebec. I confess that I’d forgotten about those wildfires. The news cycle has moved on. The novelty-obsessed media has turned its attention to other stories. Yet here is the hazy evidence that the forests are still burning a thousand miles away.

The air-quality index in Grand Rapids on Tuesday afternoon was a dismal 251, firmly in the “very unhealthy” range. (50 is considered “good.”) The sun struggled to pierce the smoke, because the air pollution in West Michigan was worse that day than in any major city in the world.

The fires have reminded me yet again about the lies we sometimes tell ourselves: lies about borders, lies about boundaries, sweet and tempting lies about the possibility of independence. Here in the air that smells like a hundred campfires, we get the truth and the rebuke: Our lives are deeply intertwined with those of our neighbors near and far, with those of the trees and the forests, with those of the good, if fragile, earth.

A couple of weeks ago, I read about a growing water crisis in the southeastern corner of Iran. For centuries, snowmelt from the mountains across the border in Afghanistan and spring rains would feed Lake Hamun and the surrounding wetlands. Today, thanks to persistent drought as well as diversion of water for agriculture and human consumption, the flourishing wetlands have turned into desolate salt flats. The lake is no more. What was once a regional oasis is drying out. Drinking water must be trucked into many communities. Fishermen have nothing left to catch. Dust storms now plague the area for dozens of days each year.

I’ve been thinking too of a lake in my native California, no more than a few hours’ drive from where I grew up. I can’t find this lake on Google Maps, because according to Google Maps, it doesn’t exist. Yet the folks who once lived in the 180 square miles now covered by Tulare Lake’s waters can tell you that it is very much real. They can testify to how those waters have swallowed their crops, their farmland, their homes, their livelihoods. And the lake? The lake, which humans thought they had tamed, might say: But I was here first, until you tried to make me go away.

Tulare Lake was once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi. Thick stands of tule, a type of bulrush, marked its shores, growing five, seven, ten feet tall and feeding a species of elk that lives only in California. The ecosystem that included the lake and the rivers that fed it sustained the Yokut people, who fished for salmon and trout, gathered clams, trapped crayfish, and foraged for acorns, seeds, and berries. They called the lake Pa’ashi (“big water”).

According to one Yokut myth, in time immemorial, a great flood had destroyed all the land, leaving only a giant expanse of water. In the midst of that water rose a single oak stump. Eagle and Crow, who had both survived the flood, shared this remnant stump, but it was an uncomfortably small home. Both noticed that, when Duck went fishing beneath the water, it would resurface not just with fish but also with mud. So Eagle and Crow hatched a plan to encourage Duck to bring more mud up: If Duck brought them mud, they would reward Duck with fish on the stump. Slowly, they began to build an island around that stump, which became the world the people inhabited.

The lake remained. And Duck was eventually joined by other birds—cormorants and sandhill cranes, dowitchers and avocets, western grebes and cinnamon teals—which found feasting and rest here. Guided by two Yokut children, a famed mountain man named John Adams made his way to Tulare Lake in 1854. “There were birds in almost incredible numbers—ducks, geese, swans, cranes, curlews, snipes and various other kinds, in all stages of growth, and eggs by the thousands among the grass and Tules,” he wrote. “There were also beavers’ works in almost every direction; and we saw also elk in numbers, which fled into the tules at our approach.”

To most settlers, though, the marshlands that spread like an apron around the lake’s edges were little more than a malarial nuisance. In the 1800s, they grew determined to make the land “useful.” They evicted the Indigenous inhabitants and began draining the wetlands and then Tulare Lake itself. “As water is the chief boon to be desired by all the colonists, the very existence of the lake is threatened, and the peace of its denizens is already wellnigh at an end,” the Scottish travel writer Constance Gordon-Cumming wrote in her book Granite Crags of California, after visiting what remained of Tulare Lake in the late 1870s. “The poor lakes have simply been left to starve—the rivers, whose surplus waters hitherto fed them, having now been bridled and led away in ditches and canals to feed the great wheat-fields.”

Twice in the first half of the 20th century, the lake re-emerged after heavy winter rains and snows, reminding the settlers of what once was. So they simply redoubled their efforts, building higher dams and stronger levees. It happened again in 1969 and 1983, when the waters didn’t recede for nearly two full years. As industry grew, though, drought and overproduction meant that the diverted rivers couldn’t provide enough water for these large-scale farms. So farmers relied on ever more sophisticated pump systems to extract groundwater from ancient aquifers. The perverse result: the old lakebed sank, making it even more vulnerable to flooding.

After the inundations of this past winter, Tulare Lake is back. Already, it has become the second-biggest freshwater lake in California, after Tahoe, covering more than 180 square miles. It’s remarkable how quickly life has returned as the lake has resurrected. Fishermen have caught carp, bass, and catfish, and birders have spotted clouds of blackbirds, flights of swallows, and congregations of ibises.

Groups of sandpipers have been seen on the shores of Tulare Lake too. I love that a group of sandpipers is called a “contradiction,” so apt to describe their survival even in a degraded environment. These sandpipers feed on insects and crustaceans found in mudflats and wetlands and on the edges of lakes. But what’s in and around Tulare Lake now is heavily polluted by agricultural chemicals, chicken manure from massive poultry farms, fuel, and other markers of human activity. The very thing that should give them life might now endanger them.

Humans had a hand in all these crises. While the wildfires in Quebec are believed to have been lit by a lightning strike, the unusual dryness of the forests is connected to climate change. In Iran as well as in California, agriculture’s thirst has played an enormous part in the devastation of the ecosystem. Again and again, we have sought to impose ourselves onto the land, fighting nature rather than working with it.

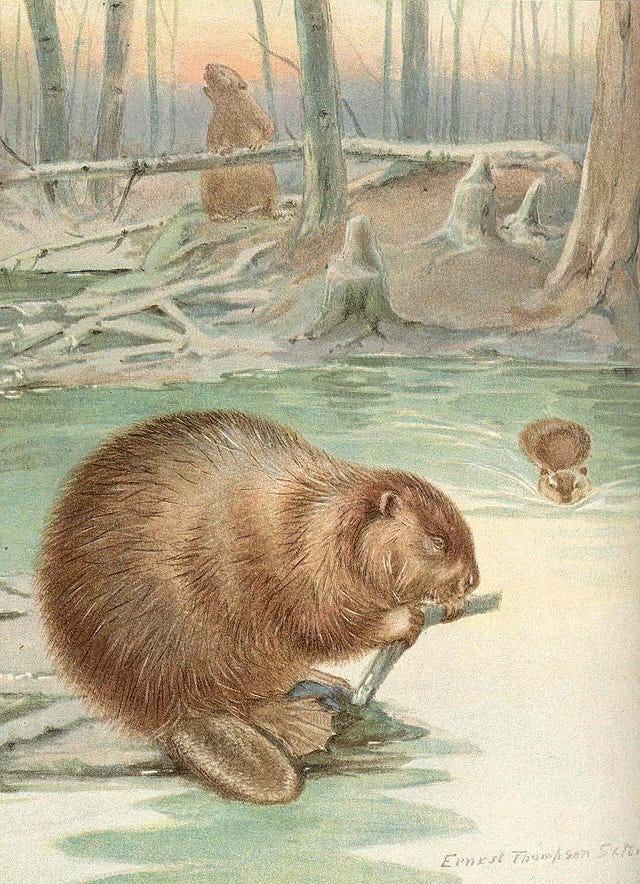

Last fall, I read an intriguing New York Times story about a rancher in Nevada who was trying a different strategy. Instead of killing beavers, as his father had, Horace Smith decided to let them do their thing. As the beavers dammed creeks on Smith’s land, the watercourses began to meander more. The wetlands expanded. When drought came, the pools created by the beavers became a source of sustenance for Smith’s cattle. When rains returned, the beavers’ innate landscape engineering helped slow and distribute the deluge.

Scientific research has begun to uncover the truth that the resilience of nature’s systems might offer bountiful wisdom, especially as the earth continues to cry out. Biologists have found, for instance, that, when beavers are left to do their thing, they help build natural fireproofing. Trees in the well-watered areas on either side of a beaver-dammed creek have a much better chance of surviving wildfires than those where the creatures have been eliminated and their engineering replaced by the human version. “Ultimately, the scale of changes that need to occur are beyond what we can accomplish and maintain on our own,” the authors of one paper wrote. “We must acknowledge the critical role that biological components play.”

In other words, perhaps rather than seeking to tame or conquer nature, we might try learning from it and coexisting with it. We’ve done such a poor job of caring for creation. We’ve been bad neighbors. What might happen if we instead honored the rest of creation? And what if we paid attention to how the other parts of creation, just by doing what they know how to do, might also be able to help care for us?

What I’m Cooking: Our friend Kenji came to visit for a day and a night earlier this week. Before he came, I texted him to ask if there was anything in particular he wanted me to cook. “I love your fish,” he wrote back. “With the ginger and scallion?” I asked. “And the sweet, sweet oil,” he replied.

My fish dish is a variation on the traditional Cantonese steamed fish, which is bathed in soy and what seems like a startling amount of oil. But rather than using whole fish, I usually use filets—a concession to those of my friends and loved ones (not naming names) who have told me that they don’t really like the eyes of the fish looking at them while they eat. Choose a flaky white fish; my favorite is halibut, which is what I made for Kenji, but that tends to be expensive. Flounder works well. I often use cod. I get about a pound of fish for four people. You’ll also need a tablespoon or two of finely chopped fresh ginger root (depends on how much you like ginger), two green onions, neutral oil (canola or avocado, definitely not olive), and light soy sauce (Kimlan is best).

Preheat the oven to 400°F/200°C. Chop the scallions finely and put the white parts on the bottom of a baking dish. Then put the fish on top of that, and the minced ginger on top of that. In a pan, heat some oil—here is where my measurements get fuzzy, but maybe 1/8 to 1/4 of a cup, depending on how much fish you have and how thick the fillets are—and toss the rest of the green onions in when the oil is hot. (It should sizzle) Swirl it all around for a little bit, for no more than 20 seconds, and then pour the hot oil and the green onions all over the fish. Pop it into the oven for about 10 minutes; if the fillets are really thick, it might take 12 or 14. You'll know it's done when it's all just opaque and the fish flakes easily. Pull it out of the oven and drizzle soy sauce over all of it.

On Monday, I served this with white rice (absolutely necessary for soaking up all the soy oil from the fish); bok choy, simply sautéed with some garlic; braised mushrooms and garlic scapes from the backyard along with abalone that my aunt recently sent from Hong Kong, atop blanched lettuce; and spicy tofu. The next day, I told Tristan that I thought it had been one of my better meals recently—and I thought I cooked more freely because I knew what Kenji wanted and because, as I cooked, I felt the good company of a longtime friend. Food always tastes better when it’s cooked with love—and when the cook feels loved too.

What I’m Reading: Four years ago, I met up with my friend Cari for a very hard day of hiking as she made her way up the Appalachian Trail. That one day was incredibly humbling: For the first time in my life, I felt the reality of all the moving parts in my knee, which, by nightfall, were screaming at me for the burden I’d placed on them.

Cari had been on the path for four months by that point, trekking her way northward from Georgia. A few days later, she fell, breaking her ankle and tearing ligaments and tendons, which put a premature end to her hike. But earlier this month, she set out on the trail again and I so admire both her perseverance and her thoughtfulness. She’s a lovely writer, and she’s sharing reflections as she makes her way, now with her dog, Ollie, by her side (or up ahead). In her latest post, she reflects on how she’s doing what she’s doing: “I didn’t come out here to break speed records. I didn’t come out here to prove I could finish what I started. I came, in large part, as a pilgrim: one walking an established route, with fellow sojourners, toward a goal both geographical and spiritual,” she writes. “I came to discover delight along the way. I came to heed the original AT purpose set out by co-founder Benton MacKaye: ‘To walk, to see, and to see what you see.’ And you can only really see what you see, when you walk slow.”

Here’s to the pilgrim’s life, to discovering delight, and to long, slow walks, wherever they might take you.

We always say that Fozzie is a fighter. He seems mostly to be doing better. One of the symptoms of his old age is increased anxiety, which expresses itself mainly in whining, whimpering, and poop. Maybe not so different from some humans? The vet has him on canine Prozac, which we have learned is exactly the same as human Prozac, except that it’s not called Prozac: It’s called Reconcile. I’m still trying to grapple with the philosophical, psychological, and branding implications of that.

That’s all for this week. As always, I’d love to know what’s going on with you.

I’m so grateful we can stumble through all this together. I’ll try to write again soon.

Yours,

Jeff

Jeff,

Reading your letters feels like the adult version of a visit with my childhood best friend, Fred Rogers.

The way you share what is going on in your heart and in your life and connect it back to the world and history...it's beautiful. Thank you for making each day special just by being you.

How long, O Lord...just how long will it take us to learn that we were created to be in community. Together. To co-exist and trust in the gifts of our differences. As always, I am deeply grateful for you and your writing Jeff.