A Dork's Confession

Some fragmented thoughts on stamp collecting, the postal service, gardening missteps, blueberry-lemon bread, and calming music

The 78th Day after Coronatide*

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Hello, friend.

An incredibly dorky thing about me: I collect postage stamps. When I was a kid, my great-uncle and uncle ran a stamp shop in Hong Kong, and that tiny space was my version of a candy store. (I’ve never had much of a sweet tooth.) Another uncle was an avid philatelist and regularly sent additions to my collection.

Stamps are miniature artworks and tiny tickets to other places and cultures. Every time I opened one of my albums or sifted through a new dispatch from my uncle, I’d be transported to a far-off land that I hoped someday to visit in person. The names just entranced me, all the more so if I could barely pronounce them: Nagaland, Dahomey, Djibouti, Bophuthatswana.

Stamps tell stories of colonization and nationhood. You can trace the British Empire’s decline by the gradual disappearance of the silhouette of Queen Elizabeth II from postage all over the world. And across the map, territories have traded colonial-era names for new ones: Nyasaland became Malawi, Portuguese Timor became East Timor, and Ruanda-Urundi became separate countries, Rwanda and Burundi.

Stamps reveal something about what a nation values; almost all countries like flowers and animals and dead celebrities. But only China has issued a stamp backed with adhesive meant to taste like sweet and sour pork; this was for the Year of the Pig in 2007, and, thankfully, I do not believe China has done this with the zodiac’s other creatures. And only the fishing-dependent Faroe Islands have produced stamps made from codskin.

Stamps record social change. The only woman to appear on a U.S. stamp before the turn of the 20th century was Spain’s Queen Isabella, in an 1893 set marking the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the Western Hemisphere. Martha Washington got a stamp in 1902, followed by Pocahontas, the first Native American ever featured, in 1907. The first Black American to be so honored was Booker T. Washington, in 1940.

The remarkable equity of the postal service is a story we don’t often consider. In the U.S., that 55-cent sticker will get an ordinary letter wherever it needs to go in the country. It costs no less to send it down the street than it does to get it all the way to Supai, Arizona, where all mail is delivered by mule; or to ZIP code 48222, which serves ships on the Detroit River via the tugboat J.W. Westcott II; or the Aleutian island of Adak, Alaska, the westernmost post office in the fifty states, reachable only by plane and closer to Petropavlovsk, the largest city in Kamchatka (that’s for you, Risk fans), than to Anchorage.

All this trivia fascinates me. I used to read the almanac for fun. I told you I was a dork.

My family, like much of the Chinese diaspora, has long benefited from the public service that postal agencies provide. After my mother immigrated to the U.S. from Hong Kong in 1971, phone calls were largely cost-prohibitive, and flights were even more so; she didn’t return for a visit for 12 years. Letters were her main link to her family back home, and though I struggled to read the Chinese characters, I always thrilled to the arrival of correspondence from my grandfather, whose tidy script filled pages of thin, crisp, slightly crinkly airmail paper. And the summer after I graduated from college, I spent a month in Ghana. Internet time was expensive, so I’d bang out short emails just to let my parents know that I wasn’t dead. Postcards and aerogrammes carried fuller accounts of what I was doing and learning and seeing.

While I love hearing from friends or family via text or email, a letter or a postcard still brings its own particular cheer. Not everyone agrees. An acquaintance once told me that postcards were rude, because they flaunted trips that the recipient did not get to take. I found this argument odd. To me, it seemed nice to be remembered. A postcard physically represents thought, time, and investment. But hey, that’s one person off my postcard list!

A law enacted in 1970 specifies that the Postal Service’s job is “to bind the Nation together through the personal, educational, literary, and business correspondence of the people.” We’ve heard much in recent days about the U.S. Postal Service’s struggles to do that as effectively as it has in the past, especially with cuts ordered by the new postmaster general—though amidst the ensuing uproar, he temporarily halted implementation. Post offices in multiple states had reduced their operating hours. Letter boxes and automatic sorting machines were removed. Postal workers were ordered to clock out even if their work wasn’t done. And people all across the country have reported severe slowdowns in receiving mail.

These operational changes came ahead of the most contentious presidential election in memory, being held amidst a pandemic. I’ve tried to balance my own worries against my confidence in postal workers. Just before Christmas, the Postal Service processes some 800 million pieces of mail per day. Even if every single voter decided to vote by mail this year—that’s roughly 230 million people—and did so on the same day, we’d be at about a quarter of a peak-season mail day. For now, the capacity is there.

But any slowdown risks far more than just this election. The postal service is a lifeline. It brings connection to those who are housebound. It delivers prescription medication to thousands upon thousands of people, many of whom have no other option. Hundreds of thousands of Americans still receive their Social Security checks in the mail. A few communities even rely on the mail for food and other essential supplies. Zero tax dollars go to support this public service.

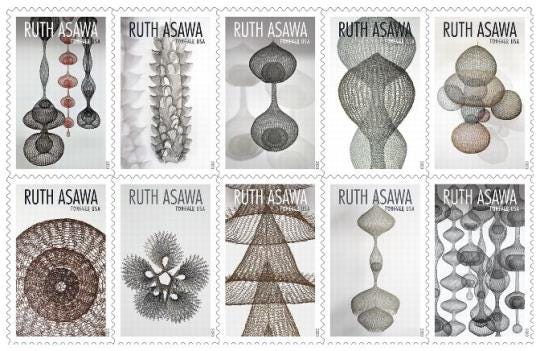

Last week, I went online and bought some beautiful stamps. Of course I chose the ones featuring fruits and vegetables as well as another set celebrating botanic gardens. And a gorgeous recent issue honors the Japanese-American artist Ruth Asawa. I’ll save some for my collection, and I’ll use some to send letters to people I love.

I never thought that buying and using postage stamps could be an act of resistance. But in this topsy-turvy time, maybe it is. To write a letter pushes back ever so gently against our culture of instant gratification. With every sentence scrawled, the ache of my out-of-shape hand reminding me that it’s still very different from electronic communication. And to send a letter honors and supports the Postal Service, something that we have too easily taken for granted.

Other people have concocted creative ways to boost awareness of the postal service. Artist Christina Massey created the USPS Art Project. The idea: One artist begins a work, then mails it to another artist to finish. Collaborative works made for the project are now on show at the Pelham Art Center in Pelham, N.Y. (different iterations of the exhibition will travel to New Haven, Conn.; Dallas; and Denver this fall).

Shortly after I started this newsletter, early in Coronatide, I made an offer that it’s time to renew: If a loved one of yours could use a word of encouragement from a random stranger, send me a note (jeff@byjeffchu.com) or just reply to this if you received it via email. There’s so much grief, loss, and uncertainty right now. Send me their name and address and perhaps a line or two about what’s going on with them—without violating confidences, of course. I’d be glad to pop something in the mail to them.

What I’m Growing: People think I’m being falsely modest when I say I don’t know what I’m doing. Ahem. Earlier this season, my friend Hana sent some long-bean seeds. She warned that they were from last season. I planted them. Something grew. I put bamboo stakes in to support two seedlings that emerged in roughly the right places. I have no long beans. I am sure this is a weed. Such pretty flowers, though! I hope they felt my (misplaced, disordered) affection. Now they shall die.

What I’m Cooking: Our approach to appreciating the seasonality of the farmers’ market is to eat our favorite things until we’re sick of them. There are still blueberries at the market, and we’re re-watching the Great British Baking Show, so though dessert is a rare treat in our home, I decided to make a blueberry-lemon cake last weekend. I used this as my base recipe, with two tweaks: I doubled the amount of lemon zest, and I cut the sugar to 3/4 c, because nearly every recipe is too sweet for us and I’ve rarely found it problematic to slash the amount of sugar. Almost all recipes for glaze call for confectioners’ sugar, which I don’t keep on hand. So I combined 3/4 c granulated sugar, 1/4 c of lemon juice, and 2 T of butter in a saucepan and warmed it over low heat until the sugar was dissolved, and it worked just fine.

What I’m Reading: A friend of mine linked to this Smithsonian story about kudzu. It’s a few years old, but in light of how stories grow and sprawl like our fantastical notions of that vine, it has new resonance. The power of the imagination is strong. So is the effect of our failure to see how narrow our perspective might be.

Another reason I’m semi-secretly a doddering old man puttering about and talking to his plants: I love reading gardening columns and coverage. Here’s an interview with Marcus Bridgewater, the TikTok gardener (if you had told me a year ago that such a phrase would ever emit from my keyboard....). It just begins to hint at the healing power of planting, tending, and harvesting, but it’s good to see more and more writing in the mainstream media about growing things.

What I’m Listening to: Lately, I’ve craved music that calms and encourages. My friend Wes, who has excellent, eclectic taste in music, introduced me to the late Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson, whose absorbing electronica has been described as “post-classical,” whatever that means. “Flight from the City,” from his album Orphée, is especially stunning, but I love (almost) the whole album.

Last Sunday, I led a Sunday-school class about the story of Hannah, from the Book of I Samuel. The English composer James Whitbourn has set Hannah’s prayer (I Samuel 2) to music. The prayer, a precursor to Mary’s Magnificat, is beautiful to read; it’s even more moving when heard in this setting.

Thanks for indulging my dorkiness. I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Best,

Jeff

*I’m counting the days from June 1, when my governor, Gretchen Whitmer, one of the finalists for the Democratic nomination for VP (!), ended Michigan’s stay-at-home order. Why are we making this so hard? Why do rights matter more than responsibilities? For the love of God and the sake of our neighbors, please wear your masks. Stay safe.