A Letter from Lviv

Some fragmented thoughts on the work of the Ukrainian icon painter Ivanka Demchuk, the ongoing toll of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and hoping for peace

Monday, March 21

Cary, North Carolina*

Hello, kind reader.

I don’t usually write to you on Mondays. But over the weekend, I exchanged messages with the Ukrainian artist Ivanka Demchuk, who lives with her family in Lviv, the largest city in Western Ukraine. With her blessing, I wanted to share with you some of what she had to say.

“It’s more or less safe at the moment,” she wrote. Which isn’t to say that life is exactly normal. On Friday, Russia sent missiles flying toward Lviv for the first time, attacking a military facility at the city’s airport. “Almost every night, we are waking up because of the alarms informing about possible air attacks,” Demchuk said. Despite the sleep-interrupted nights, daytime in Lviv has still remained relatively peaceful and stable compared with other major Ukrainian cities: “The city is functioning quite well... We have access to all the necessary things we may need.”

With so much of the rest of the country under assault by Russian forces, Lviv has become something of a safe haven. Auditoriums, gymnasiums, conference rooms, and theaters have been turned into shelters for the displaced. Its population has swelled by nearly 30% as it has welcomed more than 200,000 refugees from other parts of Ukraine: “Our city at the moment is kind of a Noah’s ark,” Demchuk said. “People from all over the country are coming here in search of safety, with their cats, dogs, birds.”

Demchuk was born and reared in Lviv. The city has long been one of Ukraine’s cultural capitals. At various points in its eventful history, Lviv has had significant Polish, Jewish, and Armenian populations, and its old town, a Unesco World Heritage Site, bears the diverse architectural fingerprints of empires past. A painter who specializes in modern icons, Demchuk has built her career here in part because she considers Lviv a central location “for the development of the modern icon, both because of its location on the border of Western and Eastern Christian traditions and also because of its rich cultural heritage.”

As she goes about her daily business, Ivanka has seen increasing efforts to prepare for an attack on a city with an abundance of history and art. What can be moved is being moved: “Museums and galleries are trying to hide all the collections of art,” she said. What can’t be moved is being given all manner of unusual armor. “People are trying to protect sculptures, paintings, and stained glass that cannot be hidden in the bomb shelters.” Workers have been using cherry pickers to mount plywood and metal sheeting over the ancient windows of Lviv’s many historic churches. Statues that cannot be moved have been wrapped in padding and duct tape and even surrounded by cages of metal scaffolding.

The churches, from Greek Catholic to Roman, Ukrainian Orthodox to Armenian Apostolic, boast a particularly rich variety of iconography. As a young person, Demchuk was drawn particularly to locally produced icons from the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. She noticed the ways in which those icons would incorporate unusual details. “The Western Ukrainian icon has always fascinated me with its nonstandard nature. Sometimes it was not entirely canonical,” she told me. “It was influenced by Western painting or folk art. Folk motifs were moved into traditional iconographic scenes, and new, striking images emerged.”

Such cultural and temporal interplay inspired her, and the boldness with which other iconographers borrowed and explored felt like an invitation to Demchuk to do the same. When she dives into Scripture looking for inspiration, she most often finds it in stories that tell us something about particular archetypes—“victory and loss, life and death, motherhood, sacrifice, human transformation,” she said. While tradition clearly matters to her, she also sees value in challenging it. For instance, iconography customarily has a gold background, but most often, Demchuk’s icons are set against a field of white. Gold and white “both symbolize light,” she explained to me. “But gold is still identical with wealth and power, while white embodies order, purity, and simplicity.”

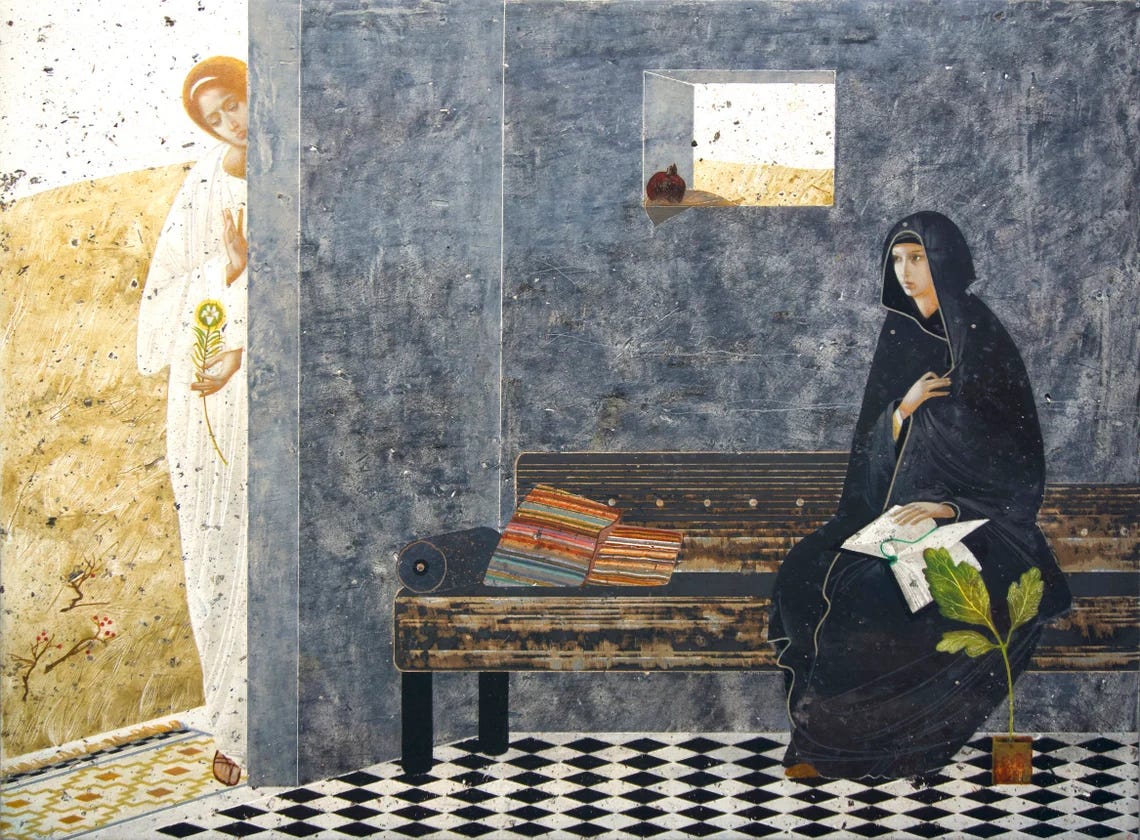

That de-emphasis of exaltation reflects Demchuk’s desire to minimize any gap between the viewer and her icons; she wants you to be able to relate. So she sometimes chooses to place her featured saints “in modern interiors or imaginary landscapes—in some ways unreal and remote, and in some ways close to the humans of our days,” she said. She occasionally tweaks traditional characters, giving them nontraditional characteristics. For instance, in her icons of the Annunciation, the angels are wingless. “This is based on the desire to bring them as close as possible to human,” Demchuk explained. “In general, in my works, I want to reduce the distance between the Creator and the creation, to point to the divine origin in man. The main aim of these works is to contact us and to be among us. So we can look at the icon, but see there the people around us, the people who were once, or will be, with recurring circumstances, goals, and oppressions—people involved in their stories.”

It was striking to me to read Demchuk’s sentiments in the context of what’s happening in and to Ukraine now. As an artist, she hopes to create connection, cultivate an ethos of belonging, and stir a sense of spiritual solidarity. And the same timeless themes that enliven Demchuk’s paintings are so present in her country’s story today. When I asked her where she is finding hope right now, she replied that she—“and also many of our people”—was “taking solace and inspiration” from the biblical story of David and Goliath. When I wondered whether the Russian invasion was causing her to see any of her icons in a different light or if she was finding new meaning in any of them, she named three works.

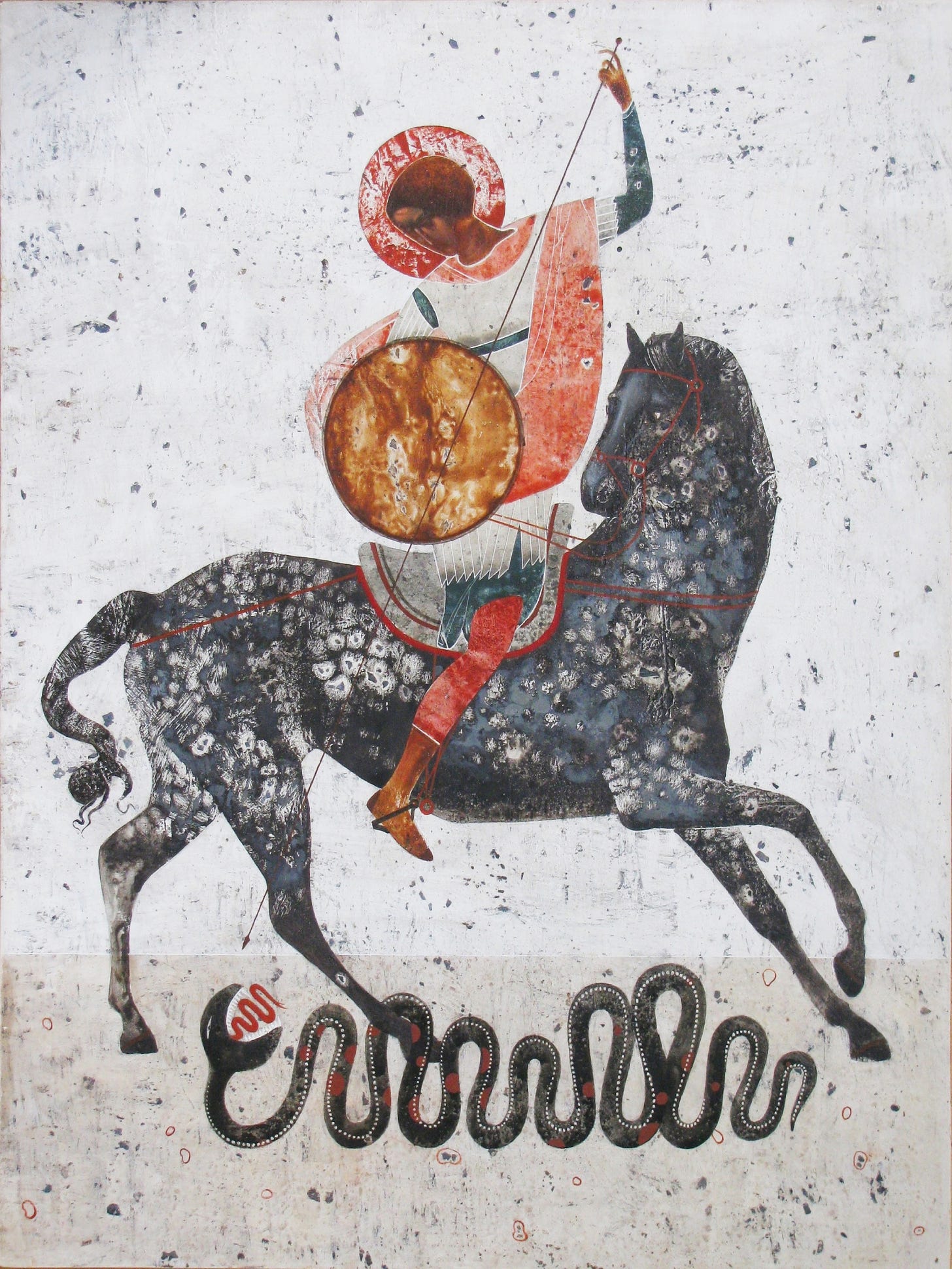

It did not surprise me that the first one she mentioned was her icon of St. George, who famously slayed a dragon. Demchuk’s depiction, in which a more familiar snake replaces the mythical dragon, helps her to believe that evil will eventually be defeated.

Her choice of “The Shroud of Christ” was somewhat more surprising to me. Demchuk told me that she draws strength from it because it is “a symbol of the life that was given for truth and love, but will be resurrected.”

Finally, she named an icon called “Hidden Life in Nazareth.” This is one of my favorite Demchuk pieces, because of its vibrant warmth and its gorgeous scene of household intimacy.

Before I saw it, I’d never before thought of Jesus as a toddler, running toward the outstretched arms of Mother Mary. Nor had I ever imagined the quotidian reality of life in the Holy Family’s home, which Demchuk suggests with the laundry hanging on the line. “It’s an example of the calm and peaceful life that we had—and that we hope will return to our land,” she explained. “Also, understanding that people in other countries are living this peaceful life now is giving me happiness—and the belief that we will have this again.”

When I asked if she had anything else she wanted to share with people outside of Ukraine, Demchuk added this: “Ukraine and Ukrainian people are so very grateful to all those who are supporting us during these difficult times. So many people all over the world are helping with what they can and praying for us.... It’s so great to feel that we are united in our spirit. We will never forget this!”

If you would like to support Ivanka Demchuk and her family, her Etsy shop is still operating. You’ll need to be patient, because they aren’t able to ship as quickly as normal, given the conditions on the ground: “We are trying to process everything as soon as we are physically able to.”

That’s it from me today, other than to ask you to please join me in continuing to pray not just for Ukraine but also for all the other lands and peoples around the world who continue to live amidst the violence of war and the specter of oppression.

I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Yours,

Jeff

*Tristan and I have been in North Carolina the last few days visiting with the good people of Crosspointe Church, where I serve as teacher-in-residence. If you happen to be in or near Asheville tomorrow evening (Tuesday, March 22nd), I’ll be speaking on Wholehearted Faith at 7 p.m. at the First Baptist Church of Asheville. Please come! (If you’re not in Asheville, I’m told a link to the livestream will be available on Tuesday evening here.)

Thank you for sharing Ivanka, her paintings are so inspiring.

What beautiful artist, in word and deed. Thanks for sharing!