Beyond the Dailiness

Some fragmented thoughts on Min Jin Lee's novel "Pachinko," waiting and longing, pears, our favorite new-to-us podcast, and the parsley in my backyard

The 185th Day after Coronatide*

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Hello, friendly reader!

I meant to get this letter to you on Thursday. Then Thursday became Friday, and Friday morphed into Saturday, and like so much of 2020, I had to ask whether time even mattered anymore.

The blinking cursor and the blank page have vexed me for the past several days. Some of it might have to do with an intentional choice to change things up over recent weeks. I’ve largely avoided the words that regularly bombard me: tweets, Facebook posts, CNN breaking news that might indeed be broken but hardly registers as news anymore. Instead, I spent lots of time at the stove instead of at my laptop, and I read recipes, seed catalogs, and even a work of fiction.

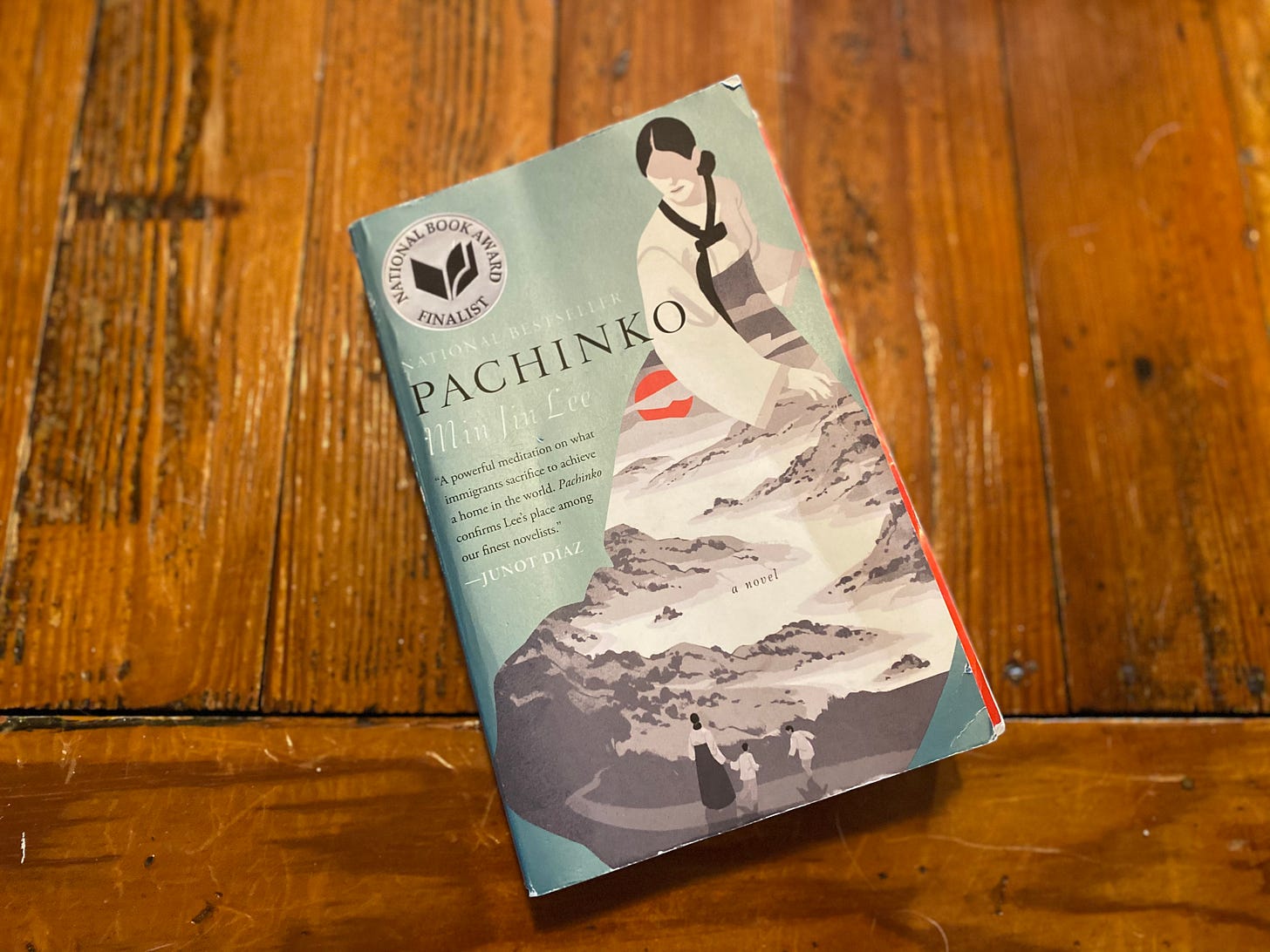

Pachinko, the acclaimed 2017 novel by Min Jin Lee, has been atop my to-read stack for a couple of years, slowly becoming a physical representation of my shrinking attention span and my growing pile of unmet expectations. If the stylized woman on the front cover had eyes—she does not—I imagine she would have glared at me with all the shame-inducing power of an Asian mom. Honestly, the firm set of her unsmiling lips was enough to do the job. And the mountains on her hanbok seemed to grow larger and larger, forbidding but beautiful terrain that I didn’t have the energy to explore.

Eventually, I got over myself and my incessant overthinking, and I just started reading. As I entered the world of a disabled fisherman named Hoonie and traveled with him and his descendants through the twentieth century, it struck me that Pachinko is about waiting. Miscarriage after miscarriage, death after death—the characters wait for children, who embody hope. House after makeshift house, they wait for home. Season after uncertain season, they wait for stability and security, and the comfort and rest that, theoretically at least, are their byproducts. Loss after loss, they wait for peace.

The waiting in Pachinko is anything but passive. Its characters wait by feeding others and offering them shelter. They wait by re-papering the walls and savoring the rare luxury of white rice. They wait by trying to discern what call and claim God might have on their lives; one of the most intriguing characters is a young, sickly Protestant pastor named Isak, who was born in what is now North Korea. They wait by trying to build possibility for their children that they can’t imagine for themselves—the possibility of education, the possibility of safety, the possibility of a different kind of life. They wait by seeking solace—in stories, in dreams, in relationships temporary and enduring, in other people. Of two characters who manage to forge something resembling love, Lee writes: “Neither had realized the loneliness each had lived with for such a long time until the loneliness was interrupted by genuine affection.”

Though Lee’s prose is elegant and fluid, Pachinko is not an easy book. At many moments, you can feel the back-breaking, breathtaking weight of carrying so much grief but also such hopeful expectation. You can also sense the openheartedness with which Lee portrays her characters and the deep compassion she brings to the mapping of the patriarchal limitations faced by Korean women, the daily discrimination against Koreans living in Japan, and the layers and layers of shame that shroud them all.

Pachinko is about purpose and meaning too, not just for yourself but also for those whom you love, and the perseverance it can take to fulfill—or discern—your call. In a world that often prioritizes instant gratification and quick wins, I’m grateful for reminders, fictional and non, that good work is so often slow work. Elsewhere, Lee has written with rare, lovely vulnerability about her own long, difficult path to publication, which she walked even as she dealt with debilitating, chronic liver disease.

In a 2019 interview with Alexis Cheung in The Believer—a conversation worth reading for all the rich insights about the redemption we seek in books, about representation, about purpose and patience—Lee explained one motivation behind Pachinko. “I wanted to understand what it means for people to decide they’re home at last,” she said. “It’s always been important to me, this sense of belonging and not belonging.”

By the time I reached the book’s end, I’d concluded that Pachinko was entirely appropriate to read at the beginning of Advent. Isn’t Advent a season about precisely that kind of longing—longing for home and longing for belonging?

Those of us who believe that Jesus was and is both God and man also believe that he came to make home for those who did not have home, not in the truest and least superficial sense, not in the most embodied and soulful and in-your-very-marrow sense. Those of us who believe in some form of the Jesus story as it has been handed down to us also believe that he came to offer us belonging that we crave yet cannot otherwise find—and purpose and meaning beyond our limited selves.

Forgive me if that’s too Jesus-jukey; I don’t mean it to be. But reading is contextual. We encounter every book, every story, with the baggage and the background of our own, which inevitably color our interactions with new characters and tales. Indeed, I wonder whether readers also always become characters whenever they engage a text, the memories and experiences they bring from the rest of their life ricocheting off those of the people they meets in their reading. And the best stories ground us in the reality that there are forces at work in the world much more powerful than any one individual—evil forces but also good ones, discord and division but also togetherness and solidarity, hatred but also love.

I entered Pachinko as I’ve wrestled in recent weeks with my own desire to find and make home, my own chronic questions of belonging, my own doubts about my calling. Much as I’d like to say otherwise, these seem to be constant companions. Of course they’re not the only ones. As Lee writes, “beyond the dailiness,” one can find “moments of shimmering beauty and some glory, too.... Even if no one knew, it was true.” And maybe there’s shimmer and glimmer not just beyond the dailiness, but also within the mundane. I have to hope that’s true, too.

What I’m Cooking (and Eating and Drinking): Every Thanksgiving, my in-laws send us a box of Harry & David pears. We’d never buy them for ourselves, so maybe that makes us love them even more. Amidst all the holiday’s heavy but delicious decadence, I did something we rarely do in our household, because my people traditionally frown on uncooked vegetables: I made salad—baby spinach; a finely sliced shallot; for crunch and spicy sweetness, pecans candied with maple syrup and sriracha; a few crumbles of blue cheese; a quick vinaigrette with maple and whole-grain mustard; and some slices of that beautiful pear.

My sister-in-law also sent us an Advent calendar, which is something I didn’t grow up with, and this one has little bottles of wine, which is another thing I didn’t grow up with. Pear, stilton, walnuts, wine... Yum. But I have to ask, Are we missing the point of Advent? [Picture my omnipresent grimace emoji here.]

What I’m Listening to: Tristan and I don’t listen to many podcasts, but we have found delight in the audible hospitality of Samin Nosrat and Hrishikesh Hriway. Their Home Cooking series makes you feel as if you’re standing in the warmest of kitchens, helping to prepare a great meal among friends. Each episode is infused with welcome and generosity. And every time I listen, I want to cook something new—and I miss even more sitting at a table surrounded by loved ones.

What I’m Growing: Though the weather has turned cold here in West Michigan, the backyard bok choy and parsley don’t seem to mind the frost at all. The parsley, in particular, is making me think that I ought to make meatballs this week; the bright herbaceousness goes so well with the fatty pork.

On a sad note, I send my thoughts, prayers, and love to my friends at New York City’s Middle Collegiate Church, a longtime witness to God’s love and justice and a refuge and a sanctuary to so many. The Collegiate Churches are the oldest congregations in my denomination, dating to 1628, when Dutch settlers began worshipping together in what was then New Amsterdam. This morning, a devastating fire engulfed Middle’s building in the East Village. The Tiffany windows, the gorgeous woodwork, the roof—all gone. But I know the resilient spirit of this family of faith will endure. If you feel called to support its rebuilding work, you can join me in donating here.

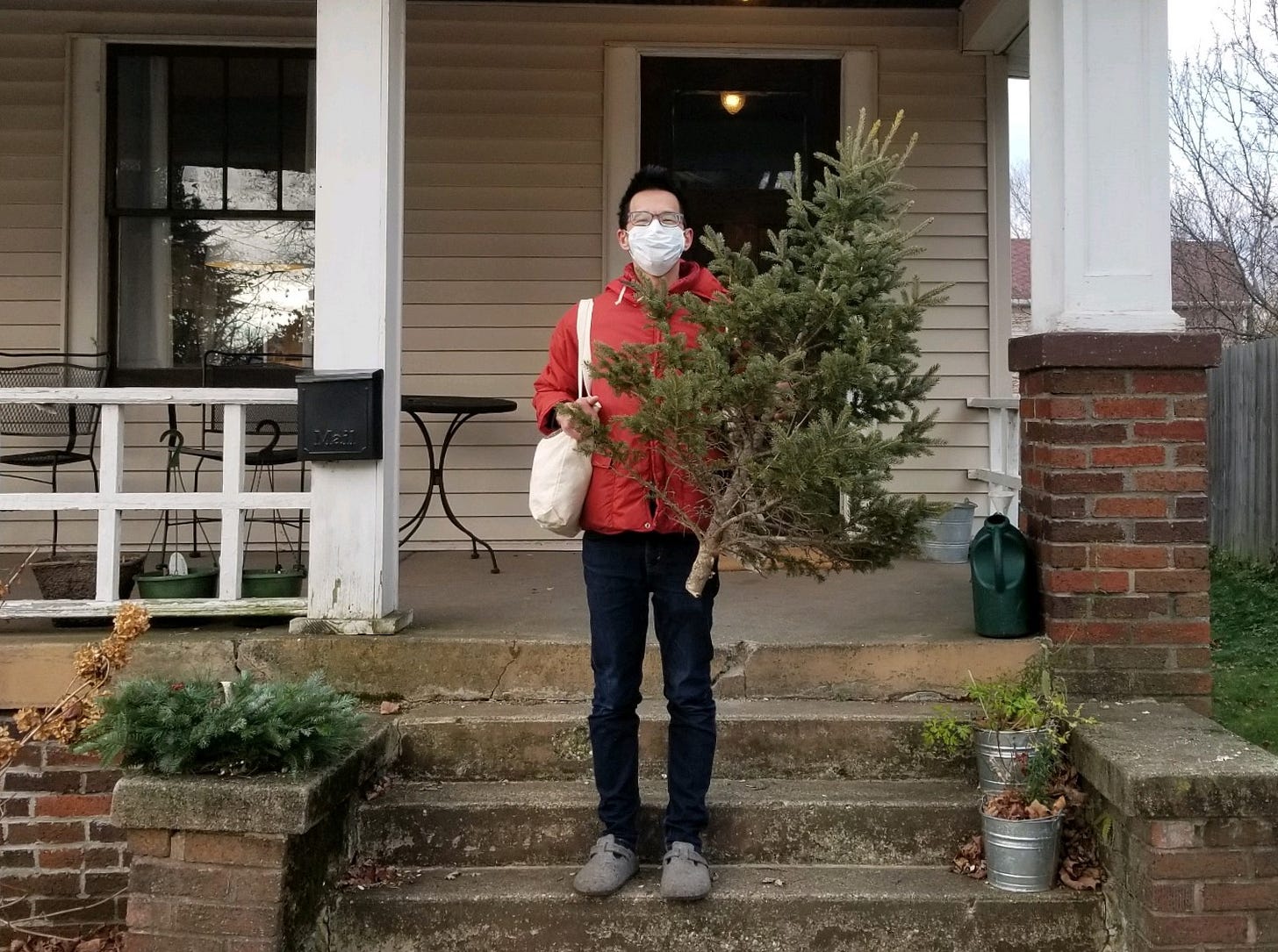

That’s it for this week. Time to go downstairs and decorate our little runt of a tree, which we bought at the farmers’ market this morning. Fozzie barked at it when it came through the front door. We just hope he doesn’t pee on it next.

I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Yours,

Jeff

*I’m still counting my days from June 1, when my governor, Gretchen Whitmer, lifted Michigan’s stay-at-home order. I would not be averse to another stay-at-home order, even if the people of this country aren’t very good at following orders. But if we can’t manage to make wise and reasonable choices on our own, choices that help keep one another not just safe but also alive, perhaps we can’t handle freedom as well as we like to imagine. For the sake of yourselves and your neighbor, please keep wearing your masks when you go out, please go out only when you have to, and please stay safe.