Doing Our Best

Some fragmented thoughts on the best we can manage, pear-zucchini bread, stories that complicate, and Max Richter's "On the Nature of Daylight"

The 148th Day after Coronatide

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Greetings, dear reader.

We’re less than a week out from Election Day, having stumbled through the most hideous campaign season and indeed presidency of my lifetime. People are still shouting uselessly at one another on social media. The grief of losses great and small and the continued toll of uncertainty have piled up day after day, month after month, throughout this pandemic. I’ve received and read story after story of anguish and shame, quiet sorrow and hidden despair.

As I’ve said before, I’m not optimistic, but I am hopeful.

At Barack Obama’s first inauguration, the writer Elizabeth Alexander read her poem “Praise Song for the Day.” What a different time it was. Yet the words of her poem are no less true, no less important, even if the light in which we understand them has shifted. “We need to find a place where we are safe,” the poem says. “We walk into that which we cannot yet see.”

Such a journey can feel so frightening because most of us like to know things. We want solidity beneath our feet and clarity on the horizon. If I have no fear that my crops will fail, it’s only because I am convinced that someone else is tending crops that will thrive. If some of us delight in braving the high wire of the unknown, it’s only because we know that there will almost always be some safety net to catch us if we fall. And if some of us like surprises, it’s only because we trust that those surprises will please us.

As I’ve said before, I’m not optimistic, but I am hopeful.

I’m hopeful because we aren’t the first to walk the way of uncertainty and we aren’t the first to fight for survival. Hopeful because we aren’t the first to lament inhumanity. Hopeful because we aren’t the first to ask bold questions. Hopeful because we aren’t the first to dare to love.

In recent days, I’ve returned repeatedly to my friend Kenji Kuramitsu’s words from Evolving Faith: “We have actually already survived the end of the world many times over. Wasn't it doomsday when the land wept in pain, when our ancestors lost everything they had? Wasn't it the end of the world when that relationship ended, when we got that news, that diagnosis, when Jesus hung there and died, didn't the world end?”

Framed like that, one might be tempted to think that we’re just stuck in an endless cycle of loss and despair—or we could summon the great cloud of witnesses that the letter to the Hebrews speaks of, witnesses who testify that there is life after death, sunshine after rain, springtime after winter, and a loving God who accompanies us through it all. “A faith that equips us to face the challenges of the present is actually a faith that will do some time traveling and ask us to go back in time,” Kenji said. “Maybe there are things that we can go back and get and bring forward into how we are living today. There is sacred wisdom in that trove of inheritance from our elders.”

Kenji’s cyclical understanding of time compels me to remember the small eschatons that have come before, the ends of others’ worlds that they had to face and endure and grieve but also survive and build upon and transcend. My grandparents shepherded not only their young family but also a bunch of Bible-college students through life on the refugee road during World War II and who then confronted a Communist revolution that ultimately ended my grandfather’s ministry in mainland China. My dad, who came to the U.S. from Hong Kong on a ship, because he was too poor to buy a plane ticket, and then was flown back across the Pacific, to Vietnam, to fight a war for a country that wasn’t even yet his own. Many endured humiliation and exile so that Tristan and I might have the life, marriage, and possibility that we have. Railroad builders and migrant workers, writers and journalists, activists and advocates—the indignities they suffered and the work they did have enabled people like me to have a more secure place in this society.

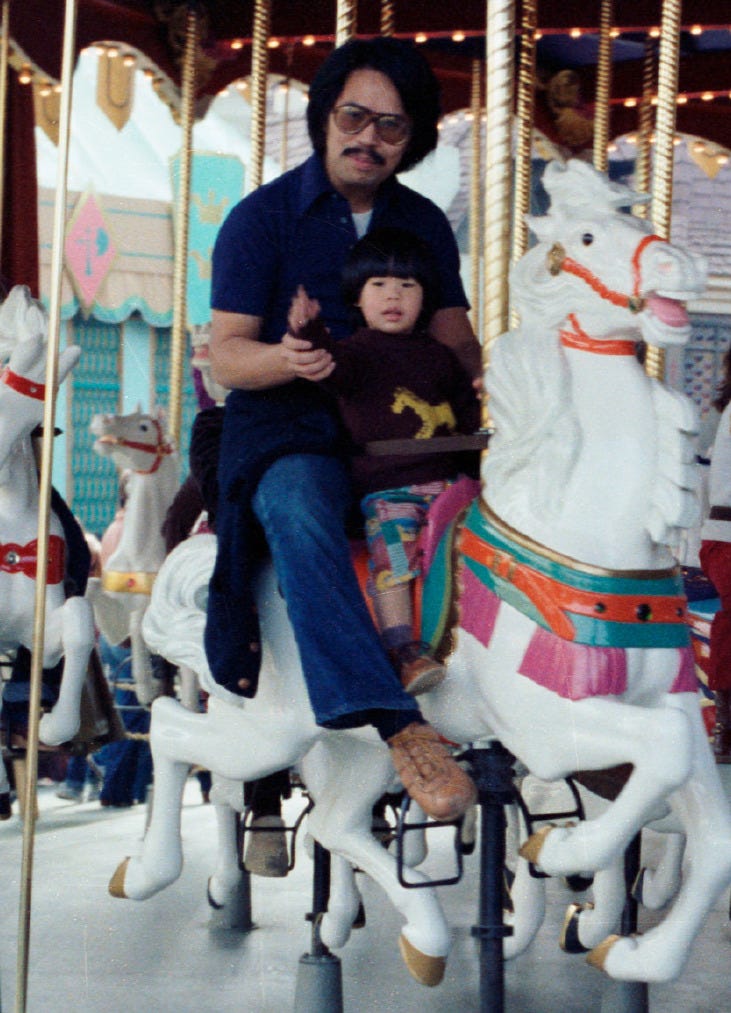

I had no other photos for this so here’s one my mom sent me recently of my dad and me. I wish I had that giraffe sweater in my current size. [Image: little Jeff with bowl-cut hair, giraffe sweater, and absurd patchwork-quilt pants, and his dad, riding a carousel horse together]

We know so much work remains to be done, and it won’t be completed in our lifetimes. One hard truth, too, is that not all of our ancestors made it—not if by “made it” we mean longevity or happiness, never-ending comfort or endless delight. It is right and good for us to grieve the costs, to lament the losses, to name the dead, and to honor the sacrifices. It is also right and good for us to honor their love by recognizing that they did make it, because we’re still here.

We’re still here because they did their best.

Full disclosure: Sometimes I’ve seen folks post on social media calling for compassion, because “we’re all just doing our best.” And my gut immediately screams, “Really?” I’ve found this line super-irritating at times, especially over the past year. If we’ve really done our best, why have 230,000 Americans died of COVID-19—a rate far higher than in nearly every other wealthy country? If we’ve really done our best, why are so many people so lonely and so hungry and so lacking in community? If we’ve really done our best, why is there still so much war and violence and recrimination and discrimination? If this really is our best, maybe we’re not as great as some would have us believe. (Cue the requisite mention of depravity—a gift for my friend Sarah Bessey.)

I sometimes claim to be a realist, but in my heart, I’m more idealistic than I like to admit. Grace and reality, though, require me to acknowledge that “our best” can be constrained by our circumstances, our sense of possibility, our limited imaginations, and our contexts. So sometimes “our best” means “the best we can manage in that moment” or “the best our limited minds can access” or “the best on a much smaller scale,” because the magnitude of more is just beyond us. A tree in drought isn’t primed for optimal growth; it just seeks survival.

So your best might be ordering takeout, because you can’t cook another meal.

Your best might be cooking another meal, because you need to escape into creation amidst destruction and you need the transcendence of something that tastes good and you need to know that you have the power to nourish yourself and others.

Your best might be letting yourself sink into the fantasy world of a good piece of fiction or the absurd parallel universe of Schitt’s Creek or the gentle comfort of the Great British Baking Show.

Your best might be locking yourself in the bathroom for a minute so that you can endure the next hour with your screaming, screen-frazzled kids.

Your best might be gazing out the window at the changing leaves of an autumn tree to tell yourself the story of the seasons.

Your best might be to double-check your properly completed ballot and drive it to the local dropbox.

Your best might be whispering a prayer or reading a psalm of lament because you have no good prayers left of your own.

Your best might be meditating for a few moments on the truth of the compost pile—life and death are realities, yes, but so is new life after death.

Your best might be stretching just a bit farther than you think you can, because your best, I’m pretty sure, isn’t just about maintaining your comfort.

Your best might be pausing for 30 seconds to text a friend to let them you love them.

Your best might be scrolling through Spotify to choose a song that gives you strength and then sharing that song with someone who could also use sung encouragement.

Your best might be an act of service to someone in your community, because you need to remember that we all belong to one another.

Your best might be to post something not about your latest outrage but about your most recent encouragement or a word that gave you hope.

Your best might be deleting Twitter and Facebook from your phone, which I just did recently and it is a good thing, because it helped to nurture that least-popular fruit of the Spirit, self-control.

Your best might be preaching a tiny sermon to yourself that everyone around you matters to God, no matter how awful or deplorable they might seem—and you matter to God too.

Your best might be any other thing that points you beyond yourself and back to love—God’s love above all, and the love that springs from that, watering new life even in the most unexpected, seemingly forsaken places.

There are a million and one ways to do your best. Maybe find just one for today.

I confess that as I was writing this, Melania Trump kept popping into my head, saying, “Be best!” Oh well. Maybe doing my best in this moment means just laughing at that, whispering a blessing upon her post-White House life, and moving on.

Let me close by quoting another snippet of “Praise Song for the Day”: “What if the mightiest word is love?” she writes. “Love beyond marital, filial, national,/ love that casts a widening pool of light,/ love with no need to pre-empt grievance.”

What if?

What I’m Growing: Not a lot, honestly. I still have to clear some stuff from my garden plot and bring in my bok-choy seeds. Sometimes your best—my best—might be admitting that I can’t do it all, taking a deep breath, and filing a task under “later.”

What I’m Cooking: We came back from northern Michigan with about 12 pounds of apples and a few pounds of pears. I baked an apple-and-cranberry pie on Saturday and canned a few pints of applesauce on Sunday. Then I made a couple of loaves of pear-zucchini bread; a toasted slice, slathered with butter—always, always, always salted butter—is the perfect mid-morning snack with a cup of black coffee. My recipe is below. Oops, I forgot to take a picture until just now, and this is all that’s left.

What I’m Reading: I’m still working through Marilyn Chandler McEntyre’s Caring for Words in a Culture of Lies with my book group. It’s so good. Here’s a snippet from this week’s reading that’s worth pondering: “But the stories that matter also complicate our lives. Good stories are always slightly precarious places to go, because even those that are deeply familiar retain the ability to surprise, challenge, and disconcert. They remind us of mysteries we have to live with and dwell in without ever arriving at conclusive or exclusive understanding.” May we remain open to such stories, to such complications, to such mysterious dwelling.

What I’m Listening to: I’d never heard Max Richter’s “On the Nature of Daylight” before this week, but once again, I’ll credit my friend Wes. Over the past several days, I’ve listened to and watched version after version. My favorite might be the NPR Tiny Desk Concert that Richter did earlier this year. I’ll always be a sucker for emotionally manipulative—a nicer way to say it might be “moving” or “stirring”—perambulations of bow across strings, seeing as I played violin and viola for years and years, and Richter’s piece does this with gorgeous effect. He wrote “On the Nature of Daylight” in the midst of the Iraq war. “I had the sense that politics was fusing with fiction,” he said. “I wanted to make a piece of music which allowed me to think about that situation.” In another interview, he explained that he was inspired in part by “the idea of trying to make something luminous out of the darkest possible elements.” He describes this work and the 2004 album that includes it, The Blue Notebooks, as “protest music.” Which got me to thinking about how creating and finding beauty in the midst of ugliness is a powerful and worthy form of protest.

That’s all I have for you this week, friends.

Oh, wait, I almost forgot. Two other things: This week, we released the last episode of Season 1 of the Evolving Faith Podcast, offering a benediction to our listeners. And I got to be the guest host on the We Wonder Podcast, which is for kids of all ages, offering a reflection on that time Jesus cooked breakfast on the beach for his friends. If you have time, let me know what you think!

May you create and find beauty in the midst of all the present ugliness. I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Yours,

Jeff

*I’m counting my days from June 1, when my governor, Gretchen Whitmer, ended Michigan’s stay-at-home order. We might be looking at another lockdown soon, though, given that cases are once again at a high—though, thankfully, mortality rates have fallen as doctors have figured out better ways to treat COVID-19. Please, please, please continue to stay safe and love your neighbor by wearing masks and physically distancing.

Pear-zucchini bread

2 c whole wheat flour, 1 c all-purpose flour, 1 t nutmeg, 1 t cinnamon, 1 t baking soda, 1.5 t baking power, 0.5 t salt, 2 c peeled and chopped pears (that’s 3-4 medium-sized pears), 0.5 c light brown sugar, 0.5 c granulated sugar, 1 c shredded zucchini (you can leave it unpeeled—this is about 1 medium zucchini), 1 c neutral oil (canola, avocado, etc.), 3 eggs, 1 T vanilla, 1/2 c walnuts or pecans (optional)

Pre-heat oven to 350 degrees and grease two 8x4x2 loaf pans. In a mixing bowl, combine flours, spices, baking soda, baking powder, salt, and nuts (if you’re using them). In another bowl, combine pears, sugars, zucchini, oil, eggs, and vanilla, and mix well. Add the wet ingredients to the dry and gently mix until everything is just combined and there aren’t any more dry spots. Divide the batter between the two pans. Bake for about an hour, or until a tester comes out clean. Cool on a rack. We usually eat one loaf right away; you can wrap and freeze the other—or give it to a friend.

Note that we don’t like our baked goods particularly sweet. If you prefer something sweeter, you can up the sugar; the original recipe I adapted used double the amounts listed above.