Falling—and Rising Again

Some fragmented thoughts about a moving new book on disability, the cultivation of compassion, eating my way through Southern California, exvangelicals, and peace

Wednesday, March 20

Grand Rapids, Mich.

None of us is immune to magical thinking: If I just did x, perhaps my problems might go away. If I just thought y, perhaps all would be well.

The British writer Polly Atkin imagined that her healing might come by swimming in the waters of Grasmere. Oswald, warrior king and preaching saint, had died in battle nearby in A.D. 642; soon, the site of his death became a place of pilgrimage for those seeking healing, but it was also said that pilgrims could be cured simply by touching whatever Oswald had touched, including the English lake. Centuries later, William Wordsworth sat on Grasmere’s shores and wrote: “If unholy deeds ravage the world, tranquillity is here!”

“I fell for the impossible lie,” Atkin told me when we spoke recently. “I did think you could dunk yourself enough and everything would be okay. I did think, I will swim and I will get better and I will be strong and not weak anymore.”

Atkin chronicles her lifelong struggle with her body in her beautifully moving book Some of Us Just Fall, which was published in the U.K. last year and is out in the U.S. this week. It is a memoir about disability and self-discovery. It’s also a meditation on opening oneself up to the wonder of the world, in all its pain and all its beauty. At its heart, Some of Us Just Fall asks deeply human questions about precarity and uncertainty: “How do we keep going? Keep moving forward when everything seems to push against us?”

--

As a child, Atkin seemed clumsy and accident-prone: “I knew I was breakable before I knew how to spell my own name.” Young Polly wasn’t the only Atkin with a strange habit of breaking bones. “Falling was just what we did in our family,” she writes. “We would joke that certain of us could trip over nothing. It’s not our fault: the ground does it to us. That you mustn’t leave a bag on the floor, because we’d fall over it. That some of us have injured ourselves by trapping one foot in an empty plastic bag and falling into it. That some of us just fall.”

She kept falling well into adulthood—at home, outside, wherever she went. Once, while walking down the street in London with friends, someone else was telling a story “about another, absent friend, about her great capacity to fall: ‘You know M, she falls down all the time, she just falls down!’ J kept walking, and I was no longer by her side,” Atkin writes. “I had fallen down a drain. The fall is all about the timing.”

She knew something wasn’t right with her body, even if she didn’t have the clinical terminology to describe precisely what. Doctor after doctor refused to believe her. An endocrinologist told her that some women are “just very sensitive.” She was accused of wanting to have cancer. Once, when she is overcome with abdominal pain, a (male) gynecologist said that it was difficult to pinpoint the source in women “because there is just so much in there,” she writes. “I imagine radiologists poring over CT scans of women’s abdomens stuffed with space junk, tin cans, old bicycles, the Loch Ness monster, an actual kitchen sink.”

“They kept asking the wrong question of my body, and when it came up with a blank where the answer should be, took this as confirmation,” Atkin writes. Yet she persisted in asking, trusting the testimony over her body over others’ disbelief.

Eventually, Atkin learned that there was indeed a name for what was happening to her body, with its “distinct parts that tumbled away from each other under the slightest pressure”: Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. People with EDS typically bruise easily and have unusually elastic and fragile skin. The condition is inherited, and it is incurable. “Everything in my body is stretchier that it should be,” she writes. “My bones do not stay where they should be because the ligaments and tendons holding them in place are floppy. My stomach overextends every time I eat and my bowel is too floppy to squeeze food along it properly. Sometimes my throat flops closed.”

Then she was also told that her body showed signs of Marfans Syndrome, another genetic connective-tissue condition—arms much longer than they should be, a mouth with an unusually high and narrow palate, an abnormally curved spine. All indicated what a doctor deemed “indicative of an incomplete marfanoid habitus.” Yes, “incomplete”: “I am part-Marfan, incomplete in my ascension, like a cartoon of a teenager mid-growth-spurt, or a shapeshifter part-transformed, completely out of sync with myself,” she writes. “No wonder I feel so awkward.”

Then she learned that she had yet another genetic condition: hemochromatosis. Her body absorbs too much iron. An element that, in the right amounts, promotes health was accumulating within her to such an extent that it had turned poisonous.

An unexpected epiphany came after all these diagnoses: “I thought things would get easier after diagnosis. That having the right words to say would act as a charm, unlocking all secrets.” That didn’t happen, and coming to terms with this inherited trifecta and the reality of their ongoing havoc is a huge part of Some of Us Just Fall. What does one do with a body that seems to be your worst enemy? “It changes the sense of how you move through the world when you’re constantly getting stuck against it, like you’ve got tangled in netting, or flown into a window, except there is literally nothing there, not even something you can’t see, or can’t imagine,” she writes. “It is just your own body, unable to cope with the gravity of real space.”

--

Some of Us Just Fall is a rangy book. The reader experiences the digressions and adventures of Atkin’s wonderfully curious mind, which takes us into scientific research and down countryside paths, through medieval history and into her memories.

For all its searching, though, Some of Us Just Fall isn’t the story of finding a cure. “Depending on your relationship to the past and future, cure is either a fantasy, or a threat,” Atkin writes. “Cure wants to undo me. To unmake me in the name of ‘healing,’ in the name of ‘wholeness,’ in the name of ‘health’.... Cure wants to remove, to erase difference. Cure wants people like me to not be people like me.”

It is, however, a story about healing. “Healing can be more of a body/mind experience than a body experience, and I think that’s really important,” she told me. “Part of the problem with ‘cure’ is that people think of it as a switch that’s flicked; you go from the bad present to the restored perfection, which for many people has never existed. I think we can have a wholeness, a healthfulness, while still being disabled and living with limitation.”

There’s often a fine line between acceptance and complacency. “Knowing how to recognize one or the other is a really vital skill, but how do we get there? How do we find that? It’s something I question all the time,” she said. “Often the difference is that complacency is to make other people feel better or to make things easier for other people. Acceptance is a deeper, more radical knowing.”

She cultivates such knowing by allowing herself to view her body as a wilderness—“not the opposite of civilization,” she writes, so much as “the state of being wild in the way wild deer are wild. It is not uncivil to be wild, if to be wild is your gracious and affable nature.” To encounter a wilderness “is not a punishment or a curse. I can see the paths and I am not alone. I go down into my body and through it, into the expanding universe. Oh what an apocalypse of the world within.”

She has also found solace in another inherited condition: the ability to delight in the seemingly ordinary. “My mum was told off at school for having a flibbertigibbet butterfly mind,” she told me. “I’m very lucky that I’ve inherited that. Small things do bring me a lot of joy. A little thing can completely transform my day and lift me out and away from that experience of pain.” The day we spoke, it was a pair of roe deer feasting on flowers in the garden of a house up the road that often sits empty because it’s someone’s second home. “The deer just don’t care. They’re like, This is my place. I live here. You may come in and do your gardening, but you’re not here,” she said. “And I thought: You reclaim that space! You go for it! It brought me enormous joy.”

--

I knew Atkin first as a poet; she led the poetry portion of a writing workshop in which I was a student. When we spoke, I confessed to her that, when I started reading Some of Us Just Fall, I didn’t realize that it wasn’t a poetry collection. Still, she writes prose with the economy of the excellent poet she is. She makes every word matter.

I wonder if this is because she understood the stakes of the story. If her main interest were personal processing, she would have consigned her thoughts to journaling, which she has done for much of her life. “One of the main imperatives was to think, What can I do with my experiences to make similar experiences better for other people?” Atkin said. “One of the things that has to happen is a shift in how we think about the ongoingness of illness and these issues around cure and incurability. How do we live with something that some people would say is unlivable?”

She hopes for change both in the health-care system and in broader society. “Most people have someone in their life who has a chronic condition; sometimes we can be quite ungenerous to people who have chronic conditions,” she explained. “For medical professionals, I hope they will question some of their biases, some of their assumptions. There is such a suspicion of patients and such a distrust of people’s narratives about their own bodies. What if we didn’t assume that ill people are insidiously untrustworthy?”

In the book, that longing for a shift from antagonism to mutual respect applies, too, to how we view our own bodies. There’s a gorgeous moment when Atkin addresses her own body. “Let us be contented in our shared society,” she writes. “[L]et us live with each other well, in kinship, in kindness.”

Was this a prayer? A request? A plea? Perhaps it’s best understood as hope-tinged testimony.

“I spent so many years thinking of the body as an enemy or myself as my body’s enemy as well. We’re in a kind of reconciliation program at the moment. Sometimes there are pleasant surprises, though, to be fair, there are more nasty surprises. I think it helps if you can look at those as, ‘Oh, that’s interesting,’ rather than, ‘How dare you?!’” she said when I asked her about those lines. “My body and I are continually in the process of trying to learn to be kind to each other.”

Such contentment doesn’t just happen. It is cultivated, hard-earned, and hard-won. While Atkin writes at length about all that her inherited stretchiness has cost her, perhaps there is one superpower it has given her too, a skill and a strength that shines through in her storytelling: an uncommonly expansive and still-growing compassion.

Yes, some of us do just fall. But as Atkin shows, with compassion’s firm but gentle helping hand, we also get the chance to rise again.

What I’m Eating: I was in Southern California last weekend. I ate so well. Some highlights: Sushi Gen in L.A., where I had an extraordinary chirashi; Sarita’s Pupuseria, in the Grand Central Market, where I feasted on a pork and bean pupusa topped with a fried egg; Huckleberry Cafe in Santa Monica, where the absurdly delicious breakfast burrito has crispy hash browns inside; and Hong Kong BBQ in L.A. Chinatown, where the ginormous bowl of roast duck and char siu with rice noodles reminded me that life is indeed worth living.

Though you all know that I’m prone to pack as if I were an 18th-century merchant, I came home with an even more ridiculous assortment of food in my luggage than usual: three loaves of bread (two from Jyan Isaac Bread in Santa Monica, one from Bastion Bakery in L.A.); two bunches of asparagus, which are not yet in season here in Michigan; a bag of blood oranges, which I’m stashing away for Easter dinner; a packet of jalapeño smoked almonds for Tristan; and three types of dried chili pepper.

We stashed some of the bread in the freezer, but we also had some for breakfast yesterday. Look at this beauty; this is Jyan Isaac’s Emmer pan loaf, made with an ancient heirloom variety of wheat that is full-flavored and nutty.

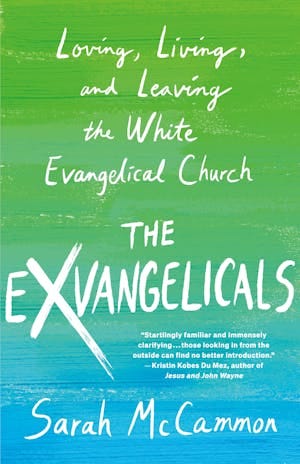

What Else I’m Reading: Also out this week is NPR national political correspondent Sarah McCammon’s book The Exvangelicals. Deeply personal and richly reported, The Exvangelicals takes a close, candid, and often heartbreaking look at people who have left white evangelicalism in the U.S. Her reflections on her relationship with her grandfather, who is largely shunned by her family because he is gay, are particularly moving. (Full disclosure: Sarah, whom I’ve known for over a decade, interviewed me for this book. I was very clear with her that I don’t identify as an “exvangelical.”)

“Peace, when I have found it, has come from accepting that I don’t have to solve the riddle of the universe or uncover any magical answers,” McCammon writes. “That life isn’t an elaborate calculus problem, and that God isn’t waiting punish us if we make an error. I don’t have the answers, but I’m not sure I’m meant to.”

As I read McCammon’s book, of course I remembered the writing of another Sarah—my dear friend Sarah Bessey’s Field Notes for the Wilderness, which came out last month. (By the way, Sarah’s birthday was just yesterday. Happy birthday, Sarah!) Especially for those who have been hurt by religion, Field Notes offers balm. I’m thinking particularly of a blessing in the book that seems a fitting benediction for this newsletter: “May you know the love of God in your most bruised places as overflowing life and healing. May you dare to believe and set up camp in the life-giving abundance of that love,” she writes. “I pray for an audacious hopefulness, one that takes suffering and loss as seriously as it takes faith and love. I know you won’t glamorize hope, you understand the grit-in-your-teeth nature of hope too well for that. When you are most wind-blown and filthy, when you lift your head yet again, I pray for a smart-aleck smile to be on your lips. May you know the companionship and guidance of the stars and the Spirit as you keep going. May all of the meaning you find and create bring you comfort and peace.”

Amen.

If you’d like to watch my sermon from last Sunday at the First Presbyterian Church of Santa Monica—such lovely people!—you can find it here.

This Sunday, I’ll be at Crosspointe in Cary, North Carolina. Last week, I preached on demons; this week, it’ll be Judas Iscariot. I make some poor life choices. Pray for me.

What’s on your minds? What can I be remembering in my prayers?

Yours,

Jeff

Thanks for sharing Polly Atkin's story. Her book sounds beautiful. As always, I so love how thoughfully you support other authors. Also, super excited about Sarah McCammon's book!

I loved this book, and am completely delighted that you and Polly know each other. Looks like part of M Thursday this year is realizing how connected the world and its table really are. Have a good one.