For All the Saints

Some fragmented thoughts on All Saints Day, the lessons of our ancestors, a big red tricycle, and the launch of the book "Wholehearted Faith"

Monday, November 1

East Sandwich, Massachusetts

Hello, dear reader.

It’s All Saints Day.

Growing up, I didn’t know much about All Saints Day. It wasn’t on the Chinese Baptist liturgical calendar. Nor did we talk much about saints, except to say that we didn’t believe in them; they were a Roman Catholic thing. In our conservative Chinese Christian culture, though, we were kind of playing a semantic game. While we forswore saints, we also venerated our ancestors. (Venerated, not worshiped, because we were good Christians!)

Saints, ancestors, forebears, predecessors: maybe it doesn’t matter what we called them. The lesson I learned was that those who came before us were always with us, sometimes in our very marrow, always in our complex stories and rich memories. When I was a child, our home always had framed portraits of my grandparents, and I remember that my grandparents’ homes always had portraits of their parents. It was our people’s way of making sure that the past was always present, of reminding ourselves that we were knit into a tapestry that was family-sized, not individual.

I should also say that in the culture of my childhood, our parents and grandparents were held in particular esteem, yes. But we also honored the elders in our extended family—aunts and uncles, great aunts and great uncles—as well as elders in our various circles of community: all the aunties and uncles to whom we were not related to them by blood, yet to whom we were still bound through relationship and respect; all the pastors and teachers, whether they taught us thundering from a pulpit or by sitting next to us and listening cross-legged on a classroom floor.

Today, photographs of my parents as well as my grandparents sit on a credenza in our dining room as well as on my writing table. When I see them, I remember and honor how each of them has helped shape me into who I am today. But it’s more than that: I also try to hold onto what I know of who they were, apart from any role they had in my life and upbringing. My dad is a U.S. army veteran who defied familial expectation to achieve significant career success. A tremendously hard worker, he has always preferred to make his bold statements through service rather than speech. My mom is no less tenacious, having paid her own way through college working as a hotel maid and a casino money-changer. She expresses her love through practical gestures—completing tax forms for relatives, delivering home-cooked meals to fellow church members in need, knitting scarves for homeless folks. My grandparents were refugees and immigrants, entrepreneurs and teachers—all four somewhat enigmatic humans with hearts for service and great love for their families as well as wounded hearts and flashes of pained ego. All of them were faithful if fallible, loving yet complicated.

When I was in Tahiti last week on assignment for Travel+Leisure, I heard from several of the people I met about the traditional Tahitian understanding of time. In their culture, you don’t look forward into the future. The idea of scanning for what’s coming makes no sense to them. Instead, the future is behind you, “because what’s behind you, you can’t see and you don’t see,” said Tahiarii Yoram Pariente, a cultural guide who is also one of the last Tahitians who has the knowledge to navigate the seas according to the ways of the ancestors, by the stars and swells and waves. “So your past is in front of you, and the future is in back. The farther in front of you a memory is, the more ancient it is.”

Herehia Sanford, a guide at the Tetiaroa Society, which guards the heritage and ecosystem of one particular atoll, told me to think about a gardener surveying her plot. “You see what you planted. That is the past. That is what you already did. Looking at what you’ve already done, you can imagine the future,” she said. There is the prospect of a harvest, of good meals to come. “But you can only do that when you’re looking at the past.”

Sanford also encouraged me to widen the lens beyond that gardener’s one planting season, because that land will inevitably carry with it the stories of seasons past—of abundant harvests and failed ones, perhaps of one’s parents’ toils, one’s grandparents’ labors. With your eyes regarding the past, “you see where you’ve come from. You can learn lessons from what happened before. You don’t have to make the same mistakes,” Sanford said. “And in their wisdom and through their stories, the past is still present. Your ancestors are still with you.”

What Tahiarii and Herehia told me was especially powerful in light of how Tahitian culture was actively suppressed during the colonial era. In the school system, children were often beaten for speaking Tahitian, not French. The Church—Catholic and Protestant, French-speaking and English—frowned on traditions like tattoo. Multiple generations lost countless legends and stories, ancient wisdom and ancestral wealth. “We lost so much, including our sense of how to approach the world. We’re trying to restore that,” Tahiarii said. “We still have our connection to the land. You can rape us. You can kill our people. You can take our land. You can steal our practices. You can forbid our language. But you can’t steal our pono.”

Pono is a multifaceted word that means goodness and harmony, righteousness and balance. Tahiarii’s insistence on pono—his own as well as his people’s—grounds him. And I use “grounds” literally: “Pono is anchored in the land,” he said. “Pono and the land were both created by the father of earth and sky, and what was made by the gods cannot be destroyed as long as that land exists, whether it is a tiny box of sand that you carry with you or even something just in your heart. It exists.”

Tahiarii’s reverence of his ancestors and his connection of that ancestral heritage to pono was deeply moving to me. I take no small amount of comfort in this way of understanding our ancestors, because this life can be lonely. From their stories of resilience and perseverance, I draw courage for mine. From the stories of sacrifice and service I’ve inherited, I summon some strength to choose the way of interdependence. From their goodness and righteousness, I find inspiration for my attempts at the same. And from the evidence of their mistakes— Well, I choose not to airbrush the histories of those who came before either. As Herehia noted, we can learn from what went wrong as well as what they did right. I don’t think it dishonors our ancestors to acknowledge or contemplate their failures. In fact, to honor their humanity and complexity is to honor them fully.

What I’m Riding: When I got to my last stop in Tahiti, the ridiculously gorgeous Brando resort on Tetiaroa, they told me that each villa came with bicycles, because it was a nice and easy way to get around the island. That brought to mind an unfortunate meeting I once had with a concrete barrier in Copenhagen; where the road took a right turn, my bicycle and I decided not to.

“I’m not great on bikes,” I said.

“We also have a tricycle!” she said. “Shall I bring it?”

“A TRICYCLE?” I exclaimed. (I don’t do a lot of exclaiming, to be clear.) Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. “YES, PLEASE!”

“Yes, a tricycle for adults,” she said, maintaining the utmost professional composure even though she was clearly questioning my adulthood.

A few minutes later, this red beauty showed up outside, and I fell in love. Many of us have heard stories of people who traveled to tropical destinations and got swept off their feet. I never thought it would happen to me.

I posted a picture of my tricycle and me on Instagram, and I asked for name suggestions, and God bless the actual human babies who were named by some of you all. I was never going to name the tricycle “Eat, Pray, Trike,” which came from a commenter whom I’d never want to shame publicly because she is a dear friend, but who also might be named Kate Bowler. Also, why did the vast majority of people who responded think that my tricycle identified as female? And do I look like someone who would name my tricycle—or anything else—“Trixie”? (Full respect, however, to the person who suggested “Trinity.”)

Anyway, I went with Harley, as in Harley Davidson. Harley and I had three beautiful days together—well, two, because one day was a total washout, and I could only look out the window and gaze longingly at my tricycle.

On the last morning, one of the managers told me that there was a golf cart ready to take me to the departure lounge before my flight off the land.

“Can I just ride my tricycle?” I said. And I did, and then I had to say goodbye, and that is the end of my story.

What I’m Watching: On one of my recent flights, I binge-watched Mare of Easttown, which stars Kate Winslet as a small-town detective. (We don’t have HBO at home.) It’s a beautifully complicated show. And I especially love any show that has a compelling depiction of clergy, especially if by “compelling,” you mean messy and intriguing and profoundly human. Did any of you watch Mare of Easttown? I am curious to know what you thought—and I am cognizant of the fact that I rarely watch shows when everyone else is watching them, so this might feel to you as if I am asking you to discuss that thing that everyone already stopped talking about. Welcome to my life!

We are also watching GBBO, which is just the soothing balm that my soul needs right now—and that my soul apparently has needed since forever. Why do the old people always struggle? Why do the producers always want them to manifest their childhood memories in meringue or tell a meaningful story in choux pastry when it would just be really nice if they made a pretty and tasty cake? Why does Freya talk like that? And why is Matt Lucas on this show? Anyway, my favorites are probably Crystelle, Chigs, and Giuseppe. If you’re watching, thoughts on this season?

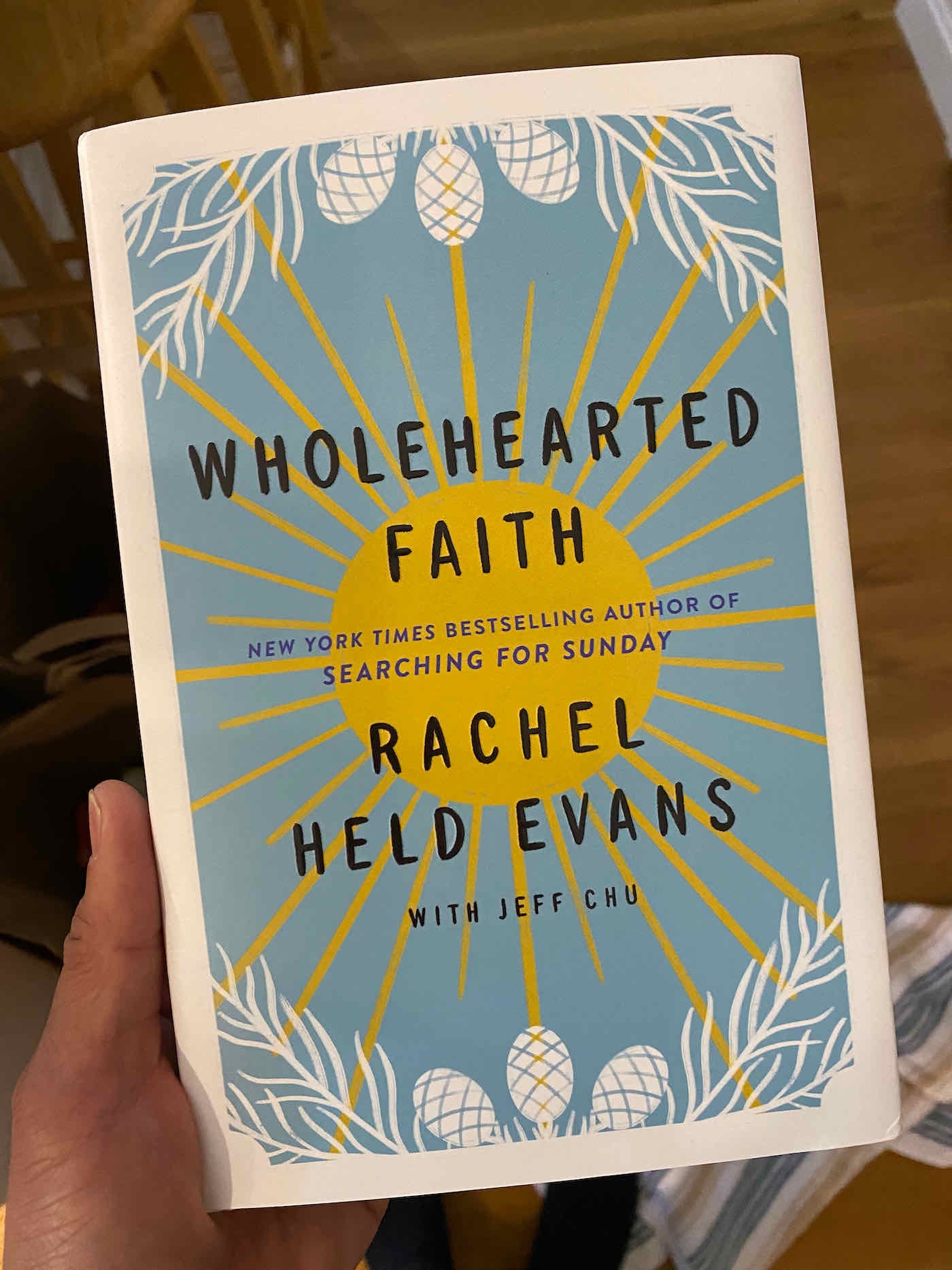

What Else Is Going on This Week: So tomorrow, Wholehearted Faith comes out. Most of you know that I have been working on finishing my dear friend Rachel Held Evans’s last book for adults for the past two years. It has been an excruciating process. People have said things to me like, “I hope you’re celebrating!” Which honestly feels a little weird to me, because it’s very difficult to celebrate something that is so intimately intertwined with the death of someone I loved—someone I still love. I don’t know how to feel about the book’s entrance into the world. Except I do know that I did the best I could, and I do know how I hope the book will make the reader feel. I hope Rachel’s curiosity, her generosity, her love, will make the reader feel openhearted and brave and beloved. Through her asking of bold questions, I hope that you might feel just a bit more courage too. Through her embrace of people who were not like her, people whom the world—and especially the Church—often treated as less-than, I hope we might all do a better job of forging belonging.

We are grateful for the interest that’s been shown in the book so far. The Pulitzer-winning journalist Eliza Griswold wrote a lovely, in-depth piece for The New Yorker about the project. Elizabeth Dias of the New York Times did a thoughtful Q&A with Dan and me. The brilliant poet Maggie Smith wrote a beautiful review of the book in the Washington Post. And I had a good chat with Sarah McCammon of NPR on All Things Considered.

If you haven’t ordered a copy of the book yet, please consider doing so. It’s a great way to support Dan and the kids. And the book is now available through your local, independent bookstore or anywhere else good books are sold. If you have already ordered a copy, we’d be so grateful if you would consider sharing about the book on social media (our hashtag is #wholeheartedfaith), leaving a review on the website of the bookstore where you bought it, and joining us on Instagram for our Wholehearted Faith Book Club (@wholeheartedfaithbookclub—very original handle). We’ll kick things off on Tuesday, November 9, with a conversation with Sarah Bessey at 9 p.m. Eastern time.

Finally, if you’re the praying kind or the good-vibes-sending kind or a conveyer of encouragements, we would welcome all such things. Pray especially for Dan, for Dan and Rachel’s kids, for Rachel’s family. This moment is so bittersweet, because, while it’s beautiful that we have one last book for adults, one more reminder of a gorgeous heart and a tremendous mind, it’s also a reminder of what’s been lost and who is no longer with us.

Today is All Saints’ Day, as I discussed above, and tomorrow is All Souls’ Day, when we more specifically remember the departed. If you’re willing to share, I’d love to know whom you’re thinking of, whom you’re remembering right now. Tell me how they have shaped you and formed you, and I’ll pray a prayer of thanksgiving for them.

That’s all I’ve got for this week. I know this is the first time you’ve heard from me in a while. I’m sorry for my silence; things have been a bit overwhelming. But I’m so grateful, as always, that we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Much love,

Jeff

I have the same questions on GBBO! I realize I’m quite late to this… sometimes emails, even those I want to read, can feel overwhelming. But I’m here… still thinking about Oma, my grandma. I just made muffins for my family for breakfast (I can’t eat them anymore, which is a whole other story), but cooking and holidays are when I think of her most. So always. But muffins, blueberry muffins in particular, she completely ruined for me. If it’s not homemade, warm and fresh out of the oven, they aren’t blueberry muffins worth my time. And I’m okay with that.

My uncle died a few months ago, following health complications resulting from COVID. He was never married and didn't have any kids. My sisters and I were essentially his kids. He was the kind of uncle who taught me how to spell "encyclopedia" when I was 5, and when I thought I was SO smart, challenged me to spell "dictionary." We used to play trivia question games to earn trips to the nearby convenience store for treats. And the teasing and tall tales! I can't count how many times he "read in the paper" that summer break was cancelled/we had to go to school on Saturdays/school uniforms were being instated. My heart cannot quite grasp a world without him in it.