Friendship in the New Abnormal

Some fragmented thoughts on borrowed hope, shared meals, soy-sauce chicken, and the new book "Jesus and John Wayne"

The 52nd Day after Coronatide*

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Hello, friends.

On this week’s episode of the Evolving Faith Podcast, my friend Sarah spoke of how people can “borrow some hope from one another” when we need to. I’ve been thinking about that phrase and how true it is for me. I borrow hope from the world around me: from the insistent song of the robins, from the resilient chives, from the perceptive rabbits who constantly elude Fozzie—and from Fozzie, who tries to chase them nonetheless. I borrow hope from Tristan, who is the steadiest loving presence in my life. I borrow hope from my nephews, whom I don’t get to see often enough. And I borrow hope from my friends.

We’ve now been in Michigan for a full six months, which means that 2/3 of our time here has been spent in the New Abnormal: locked down, physically distanced, masked. That has made adaptation to life in Grand Rapids particularly harrowing. None of my friends-who-are-like-family live in Grand Rapids. These are the friends who don’t just know about you; they know you. While they’re glad to hear any stories you tell them, they also can read on your face and your body much of what remains unspoken. With them, silence is never awkward and it does not need to be filled.

Amidst the New Abnormal, these are the friends I’ve missed most.

In the churches of my childhood, it was often said that God made us to be in community. But those congregations were also collections of pious facades, and I saw what happened when those facades crumbled, revealing the difficult, messy realities that had been hidden. I didn’t understand true community until adulthood, when I began to learn how to be a friend. So many books discuss romance and dating, marriage and parenthood, yet relatively few guides exist for friendship. Trial, error, and empathy have proved my most reliable teachers, but their lessons have often been painful, both for me and for the person on whom the fallout from the errors lands.

Sometimes I’ve tried to be the kind of friend I’d want myself. Yet that can’t be everything. We each bring our own baggage and our own particularities into every relationship, and part of friendship means making room for the other person’s. Your friend cannot and should not be a mirror image of you. That wouldn’t be friendship; that would be narcissism.

My best, deepest friendships are those spaces in which there is room—room for me to be me and room for my friends to be themselves. There’s room for laughter and tears, room for real talk and teasing, room for confidence and doubts. There’s room to be intimate and room to be distant, room to push back and room to let something sit, room to make mistakes and room to apologize. Amidst and throughout all this, there’s room to learn—believe me when I say I’m still learning how to be a good friend—as well as room for love to grow.

Cue the inevitable garden metaphor: Friendship doesn’t grow without cultivation. You can’t always control the weather around a friendship. But you can—and must—be attentive. There’s watering to be done. Weeding and composting too, with the things of death and rot addressed and transformed into things of life and flourishing. I think of beautiful interdependence—and of the Potawatomi pole-bean plants growing in my plot. Traditionally, they are planted with corn and squash. The corn provides support. The beans harvest nitrogen from the air, depositing it in the soil to share. The squash hovers low to the ground, protecting that soil from drying out and using its prickly stems and leaves to stave off pests. They thrive together, each doing its own part.

Friendship isn’t just a theoretical or philosophical concept; it’s an embodied one. Letters, text messages, Zoom, FaceTime—all these can provide some of the space a friendship needs. (You’ll notice the word “phone” didn’t appear in that list. Unless you’re one of my very, very closest friends, please don’t call me. Ever.) But there’s no substitute for physical presence and proximity. There’s nothing like being together.

Over the weekend, Fozzie, Tristan, and I drove to Ann Arbor for a day with dear friends. We sat outside their house and talked about everything and nothing. We ate at an overflowing table by their raised garden bed—an abundance of goodness with the promise of more. Of course they remembered that I don’t like corn. Of course they poured me just the right G&T and had different beers for Tristan to sample. Of course they were overly gracious about Fozzie’s weirdness; he somehow remembered his manners and didn’t poop in their backyard.

Then, on Tuesday, after weeks of text conversations about protocols and careful planning, two of my closest seminary friends arrived from Pennsylvania. They had offered to pitch a tent in our backyard if that would allow us to spend some time together. I’m not much of a hugger, but embracing them reminded me that we are embodied creatures. Physical touch, like physical space, matters. We went berry picking yesterday, and I’ve delighted in cooking for them.

The New Abnormal will continue for some time, and it’s a grief that sharing space requires so many precautions and so many preconditions. For me, meals with friends—whether we’re hosting or being hosted—are especially meaningful. “Persons matter at the table,” Robert Farrar Capon wrote in The Supper of the Lamb. To ask someone to break bread with you “is to extend friendship, to proclaim in love that you want not his, but him.” Amen to that.

What I’m Growing: This popped up in the small raised bed in our yard, so I’m only growing it insofar as I haven’t dug it up. Is it a cucumber? Squash? We’ll see.

What I’m Cooking: Our houseguests brought a magnificent gift: a chicken from the Farminary, where we started raising chickens at the Farminary during my tenure as a farmhand. I decided to make a soy-sauce chicken, and this one turned out well enough that I texted a picture to my mom.

For the marinade: In a pot just large enough to hold a whole chicken, combine 2 c light soy sauce, 1/4 c dark soy sauce, 1/2 c Shaoxing wine, 1/2 c brown sugar, 3 T sesame oil, 6 cloves of garlic (crushed), a few chunks of ginger, 4 scallions (roughly chopped), and 3 T Chinese five-spice powder, and then simmer until the sugar is dissolved. (Oh, if you don’t have different soy sauces in your pantry, just use 2 1/4 c of whatever you have.) Cool, and then marinate the whole chicken in the pot. I did it for about eight hours, turning twice, but overnight would be better.

Make sure the chicken is breast-side up, add enough water to cover most of the breast, and bring to a boil. Then cover the pot and immediately turn the heat to low—enough to maintain a gentle simmer. Cook for 30-40 minutes (30 if it’s a 3-4-lb. bird, 40 if it’s over 5 like mine was), then turn the heat off and let it sit in the hot liquid for another 40-45 minutes. Move the chicken to a plate to cool for 5-10 minutes until you can carve it. Then pour some of the poaching liquid over the carved chicken pieces. I served it with white rice, some sautéed greens, and eggs scrambled with chives and scallions.

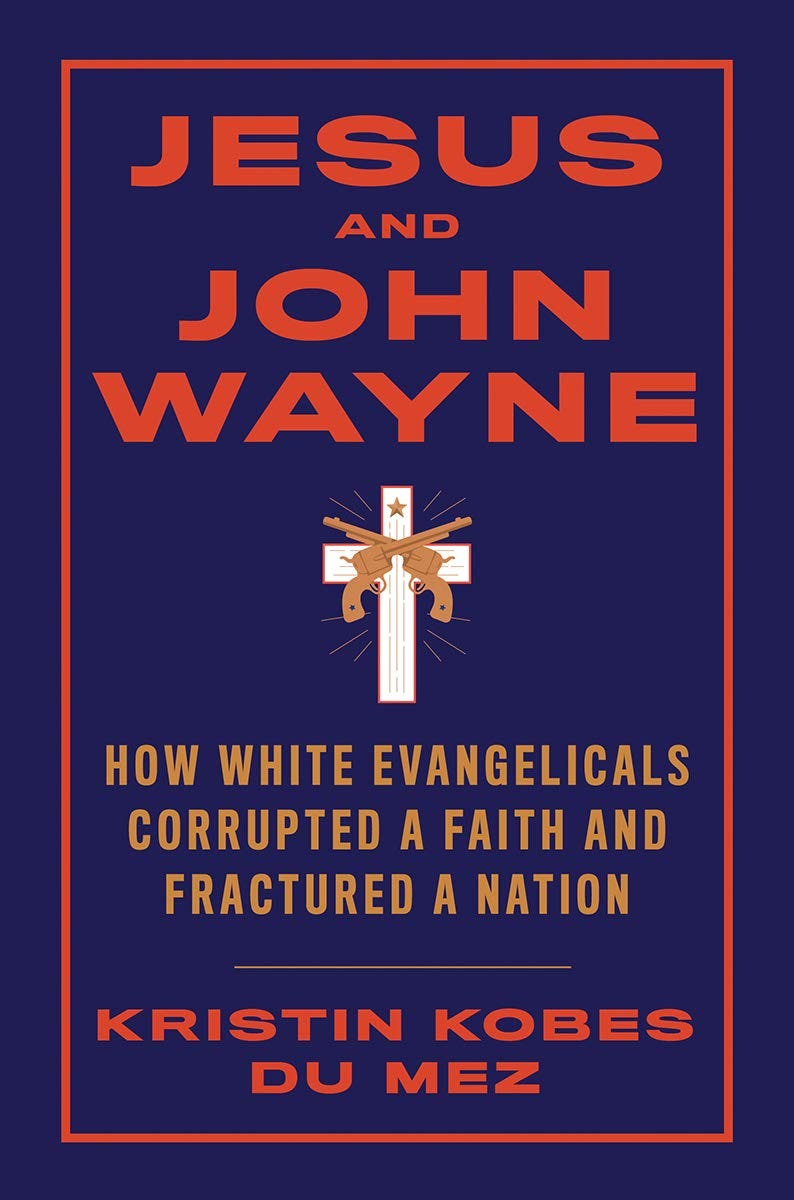

What I’m Reading: Calvin history professor Kristin Kobes DuMez’s eye-opening new book, Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation. Whew. That subtitle says a lot. I spent the most formative years of my youth worshiping with and being taught by evangelicals, most of whom happened to be white. I’m truly thankful for much of that spiritual upbringing. I also have griefs and scars from that time. DuMez carefully documents the deep cultural roots of white evangelicalism, and though she’s academic, she doesn’t write like one, which is a blessing. I thought I knew quite a bit about white evangelicalism, but really, I had no idea. Even if you’re not a white evangelical, Jesus and John Wayne is an important read, because of the profound influence that white evangelicalism has had on American politics and American life. There’s a Q&A with DuMez at the bottom of this letter.

That’s it for this week. This is a long newsletter, but DuMez’s book is important—and I don’t have an editor who isn’t named Jeff Chu. Thanks for reading. I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write more again soon.

Best,

Jeff

*Coronatide clearly isn’t over. But I overly hopefully counted its end from June 1, when my governor, Gretchen Whitmer, ended Michigan’s stay-at-home order. And I don’t know what to call this strange season. Are we in some sort of Coronagatory?

Virtue Signaling

A Q&A with historian Kristin Kobes DuMez about her new book Jesus and John Wayne

Who is this book for?

I wanted to write about white evangelicalism, not just as standard American Christianity but as a specifically, distinctively white movement. It’s white people who are least likely to realize that they have a white Christian identity. For Black Christians who interact with white evangelicals or operate in white evangelical spaces or for people of color who do so, this is obvious. For white Christians, it might not be so obvious. As a white Christian myself, this project is in the spirit of “Go get your people.”

I’m intrigued by the parallels you drew between Richard Nixon’s White House—I wasn’t alive then—and Trump’s. I had no idea.

For the record, I wasn’t alive then either—I’m not that old! One of the clearest parallels is that Nixon was coached to appeal to evangelicals, to speak their language. Billy Graham gave him the words to use to appeal to this religious demographic. You see the same thing happening with Trump—Paula White and his evangelical supporters are giving him the words to smooth over the very stark differences in order to win over that crowd. It’s very utilitarian. It’s not just Nixon either. It’s also Reagan. Time and again, you see these evangelicals embracing political figures who didn’t share their moral values, if you interpret that phrase very narrowly. If you understand “moral values” in terms of their system of family values with white patriarchy at the center, you do see an alignment of values.

In between Nixon and Reagan, you have Jimmy Carter, who, on paper, does share their Christian values. But he’s portrayed as a wimp.

He’s a Sunday school teacher! He’s a Southerner! If you want to define evangelicalism as a set of theological or doctrinal beliefs, then Jimmy Carter is your guy. He could teach you all those beliefs in Sunday school. But as certain cultural loyalties and political allegiances came to the fore as the center of evangelical identity, by the end of 1970s, that is absolutely going to trump any theological affinities. With Carter, part of the problem was they felt betrayed. They assumed that, because he was this Southern Sunday-school teacher who spoke with a drawl, he was one of them. For them, that meant he would also be anti-ERA, and he would be pro-family values in a very narrowly defined way. They had a very particular agenda to push, and expected that he would push that with them, and he did not. Then there was foreign policy. They felt that he had overseen this stunning decline of American power overseas. It was particularly galling because of this enormous fear and militancy that anticommunism fostered. That’s where Reagan came in. And Reagan had the right words to say about family-values conservatism.

Let’s talk about that fear and militancy. The militancy of the white evangelical right is a theme that emerges—and it’s not metaphorical. Much of the movement seems to thrive on threat.

I started this research in 2005 and 2006, and then I set it aside. I really dusted off the old files in 2016, for obvious reasons. At that point in time, the reigning narrative of how evangelicals could support Donald Trump was the narrative of fear. They were just so afraid—afraid for their religious liberties, afraid of profound cultural shifts, afraid because of the terrible Obama administration. They were backed into this corner, and they ran into the arms of Donald Trump—their protector, their strongman. As I looked to their own history, I saw that this rhetoric of fear was perpetual. There was always something, some crisis, that evangelicals were very afraid of—or should have been very afraid of—and were told by their leaders to be afraid of. In the early years, it was anticommunism; they’re a godless movement, they’re going to destroy the American family, and they’re going to destroy the American sovereignty. Then there was feminism, liberalism, and secular humanism. It’s just this rhetoric of fear.

But it’s not just fear at the macro level.

When I looked at Jerry Falwell Sr.’s church and Mark Driscoll’s church, I saw that this rhetoric of fear operated at the local level as well. Members were told: “Do not trust anyone outside these doors. Don’t trust the media. Don’t trust your neighbors down the street. They do not have the source of truth. We are the source of truth.” Driscoll fostered this sense of imminent threat. He had bodyguards while he preached. Were there real threats, or would he generate the impression of threat? Either way, that absolutely enhanced his own sense of power. Warfare rules apply. Loyalty is demanded. The ends always justify the means. Militancy is fueled by the sense of threat, and militancy can only be justified by an imminent threat. I also realized why people were really afraid to walk out the doors of the church and find another faith community: You leave at the peril of your own soul. Powerful men—and they were almost always men—really used this sense of threat in order to enhance this own power and maintain their own power. Once I saw that on the local level, the broader political story made sense. It takes a lot of money to run these organizations and fund these campaigns. It’s much easier to get people to donate when they feel there is an imminent threat that they can fight by contributing. I began to question what came first: the militancy or the fear? In many cases, it was the militancy.

There’s an intertwining, too, of that militancy and militarism in the U.S.

Military leaders are actually embracing this warrior rhetoric that is lifted straight out of the Christian books on masculinity. They are changing how the military operates. It’s like a revolving door. Because of this increasing militancy and militarism among white evangelicalism, members of the military have more moral and spiritual authority that ministers do—because they are true warriors. They are the ones writing the next generation of book on Christian manhood. That’s a fascinating relationship. That has not disappeared. I’m really curious to see what the next chapter of that story is.

You quote the Southern Baptist leader Al Mohler naming “the terrible swift sword of public humiliation” when it comes to sexual abuse in the church. The worst fate seems to be shame, not the sin itself.

So much emphasis has been placed on protecting the brand. They would not use that language; they would say “the witness of the church.” I admit I was shaped by that as a Christian scholar. When I first started this research 15 years ago, I was finding some really disturbing stuff. I thought, as a person of faith, “Do I really want to shine a bright light on the darkest underbelly of American Christianity?” I was morally troubled by that. Looking back, I’m uncomfortable with the fact that I was troubled. That reflects a common dynamic in evangelical circles: You need to guard your secrets and hide from the rest of the world the ugliness that is going on in your own communities, because you’re going to ruin the gospel witness. Preachers, and powerful men in particular, really get the benefit of this kind of protection. You don’t want him to come crashing down, because what will people think of our faith? That’s the exact opposite approach of what we should be taking. I quote Rachael Denhollander [who has campaigned to expose of abuse in the church]: “The gospel of Christ does not need your protection. God does not need your protection. God calls us to faithfulness.”

One striking section for me is where you document how women are objectified in some sectors of white evangelical Christianity—all the social-media posts by pastors about having a “smokin’ hot wife,” for instance. Then the objectification is cloaked in the purifying effects of the Gospel, as if quoting a Bible verse covers all. Honestly, reading all that, I felt kind of grateful to be gay (not that we don’t have our own problems with objectification).

It’s easy to roll your eyes and laugh it off and say those are the crazies. But I found it was far more pervasive and has been more than I realized. These are not outliers. This hyper-feminization of Christian women is the flip side of militant white patriarchy. It was shocking to see this, but in other ways, it made perfect sense. You have the idea that God created men with a nearly insatiable, irrepressible sex drive; He filled them with testosterone, which is important for them as leaders. For women, they really have to protect their virtue, but men can’t do that, because they’re filled with testosterone. As soon as a woman marries, it’s her obligation to fulfill her husband’s sexual needs, which are not insignificant. You have this problematic, potentially toxic relationship if you carry this to its logical conclusion. This language is everywhere in the literature of how to be a Christian woman: You have to please your husband, and you need to keep yourself beautiful. There’s a lot of emphasis on appearance, on sex, on pleasing your husband. It’s not just because God wants you to be happy or your husband to be happy; it’s to bolster that masculine ego so that he can lead and he can rule.

You say this isn’t about theology. But doesn’t this stem from how white evangelicals view God?

There’s a very lively interplay between theology and these cultural values. They’re building a theology, in part, around cultural loyalties. Some of the most fascinating points in my research were where this came through most clearly: Traditional notions of the Trinity. They were willing to make some dramatic changes there—for example, promoting the eternal subordination of the Son—to defend gender arrangements. They were also willing to explicitly say, “Forget about turning the other cheek; you can’t teach a man to be strong if you turn the other cheek.” They were willing to toss aside many of the core teachings of the Christian Scriptures and pick and choose those that promoted their cultural values, transform the gospel itself—they love the word “Gospel”—and really transform Christ himself into the ultimate fighting champion figure. Culture shapes their reading of Scripture to an enormous degree—and they are so adamant that they are Bible-believing. They don’t have eyes to see how much of their biblical interpretation is shaped by the cultural values that they hold dear.

Did you grow up with this?

I grew up in a small town in Iowa. I did not think I was evangelical. I didn’t really understand what evangelicalism was until I went to graduate school and I had classmates who went to Moody and Wheaton and Bob Jones. Then I realized I did have some points of connection. Those were largely through popular culture. I listened to contemporary Christian music. We had Focus on the Family Radio on in our home. I went to a Christian school. I was born in 1976; I was just a tiny bit too old to get the really heavy dose of purity culture. We had speakers come to our school on sex and purity, but I wasn’t quite the Josh Harris generation. At the same time, when I was in what was called Calvinettes, our activities were making crafts for our future homes and learning how to put on Mary Kay makeup and being beautiful. That highly gendered understanding was part of growing up Christian.

What about a reader who belongs to a mainline denomination? How is this relevant to them?

This has absolutely influenced the mainline. Popular culture is really the vehicle. Show me a mainline church and what books their women’s Bible study is reading. Who do they follow on Instagram? What cultural influences shape their understanding of what it means to be a godly woman or a godly man? Especially if you move more into rural churches, many are de-facto evangelical. I do not draw clear distinctions between evangelical and mainline as a sociologist would based on denominational membership. That’s not how this consumer culture I’m looking at works. There may well be members of the mainline who have been largely isolated from these influences and who might look at this as a different world, a different culture. At the same time, they have to be bumping up against this, if not locally, then certainly politically in terms of what this has done to American Christianity more broadly.

It would be too easy for some readers to see the characters in your book as fringe.

I do hold up the absurdities, but my fascination is with the question, What is really fringe? What is really mainstream? How does the center of a movement shift over time? What is the mainstream, at any given moment, willing to accommodate or embrace or smile at, while keeping a little distance and calling him a brother in Christ? Where do they draw the line and say, “You’re outside the movement”? It’s often on sexuality, and it’s often race. “Brothers in Christ” can be pretty blatantly, unrepentantly racist and still have a place in this movement. We can have some of these harsher expressions of patriarchy and sexual objectification of women and sexual abuse of women and children, and still the perpetrators, the powerful men implicated in these, are not necessarily or frequently defined outside the movement.

The question, then, is how far grace extends.

Who is extended grace? It’s the powerful—and the people who can help you achieve more power. Then it’s not actually grace, is it? That’s really a concept we need to take a hard look at. Who is not extended grace? Which lines, if you cross them, will get you kicked out of your movement or your church, where people are going to turn their backs on you in the grocery store if they see you? Grace does not abound. It’s really important that people of faith be a little self-critical on these concepts. When we talk about grace and forgiveness, is it really grace that we’re talking about?

Let’s return to race. At times it felt that, as a person of color, I wasn’t meant to be in the room.

This is explicitly a history of white evangelical masculinity, a masculine militancy very much reserved for white Christian men. One of the first signs of this: Who are their heroes? Evangelicals love masculine heroes. Teddy Roosevelt. The American cowboy. John Wayne. These are all white men who are using violence to enforce order, usually over non-white populations. It’s very important that we acknowledge that. They are not celebrating a rugged, rough, tough, violent-when-necessary masculinity for Black men or other men of color. Some Black men participate in this space—Tony Evans, for example. I’ve talked with a number of Black Christians who concede he’s kind of a bridge figure. But when you read his books, they are very hard to distinguish from white evangelical masculinity. It’s the same phrases, the same model. This is a white discourse, and people of color are invited into it on the terms of the white culture. If you can support that and make us look less racist, then sure, come on board. But if you’re calling out any aspect of this, talking about racial justice or civil rights, they’ll say you’re talking about race too much—or critical race theory, or Marxism. You can very quickly get defined out. Part of what I’m doing in this book is making the argument that we need to understand white evangelicalism as distinct from Black Protestantism or Black “evangelicalism.” In recent years, a lot of white evangelicals have been arguing the opposite: Sure, we have some racists in our midsts, and they’re embarrassing, but if you’re defining evangelicalism, then guess what? The majority of Black Protestants and the majority of global Christians are evangelicals! We have this incredibly diverse global movement, so we can’t possibly be defined by white identity! But if you look at conservative evangelicalism as a lived religion and a culture of consumption, it is a predominantly white movement and we need to treat it as such.

Where is the hope?

[Sigh] My editor really pushed me on this: Can you give us something? You get one sentence and it’s the last sentence and it’s not my strongest sentence. [“What was once done might also be undone.”] Let me see if I can do better. I’m a historian. I have great faith in the power of history, for evangelicals in particular. Evangelicals understand the values that they hold as God-given, from the beginning of time. They are not likely to see them as historical or cultural productions, created by certain people at a certain moment in time in response to foreign policy issues and domestic conditions. If you can show that things didn’t always align in these ways, if this wasn’t God-ordained from the beginning to the present, that opens things up a little bit. You can start asking “why?”, “how?” and “for what purpose?” Who ended up benefiting from these “new” constructions of biblical manhood and biblical womanhood? To do that, you have to understand relationships of power and oppression. If you use terms like power and oppression, that can be off-putting. But if you say, “Let me just show you what happened,” it doesn’t tell you what to think or where to go next; it opens up questions. That’s the hope history can give. By understanding how we got from where we were, we can understand where we are and maybe where we want to be.

How has this book changed your faith?

It was hard to spend this much time reading things that I found deeply problematic and incredibly dangerous, especially in the last three years, as I could see the harm inflicted on so many vulnerable people in this country and around the world. It was difficult to hold onto my faith when I was just surrounding myself with examples of what I vehemently disagreed with. As soon as I started writing about this research, it very quickly caught on with others. The first article I wrote on this topic went viral. Immediately, that opened me up to a new community. Many people of faith were saying, “Thank you. Yes. This was my story. It is not right.” They said, “I was never able to articulate why I was so uncomfortable with this, until I read this.” I was just getting swamped with letters from people who had moved in these spaces and were close to people in these spaces. The more I published on it, the more I found a new community—of Christians and non-Christians. In some ways, my faith is strengthened because I don’t feel like I need to defend my faith against that. My faith is not that. Enough people are living a different kind of Christian faith that I’m able to hold this up for what this is.

love your writing and am so happy to have found you and the evolving faith podcast. Just a random thought here. Many years ago I watched a documentary called Jesus Camp. It has stayed with me. Militant training and pageantry of little christian children. very disturbing...

I think her last paragraph about faith and the recognition that there are other people of faith who do not hold with the culturally white evangelical view is also a reason to hope.

when I left evangelical christianity, that didn’t exist... I found communion with atheists and agnostics and catholics and buddhists in order to find and nurture my faith. Today there are growing groups and movements and churches where that kind of view is antithetical to the doctrine preached and the grace lived.