Goodbye, Rat! Hello, Ox!

Some fragmented thoughts on Chinese New Year, the legacy of the missionaries, the holiday table, and a new book on prayer

Chinese New Year’s Eve

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Hello, friendly reader.

Tonight we bid Rat farewell and welcome Ox.

As a kid, I loved Chinese New Year. My people’s biggest festival is every gluttonous, greedy child’s dream. There’s so much food. And any friend or relative who is older and married has to give you money! The hardest part was having enough self-control not to open the red envelope in front of the giver, which is considered rude. Our gratitude was supposed to be for the gesture and the thought, not for the gross profit. But my childhood brain couldn’t comprehend that; wasn’t $20 a better gesture, a more generous thought, than $5?

As an adult, I still love this holiday—even more than I did as a kid, and even though my New Year’s giving has increased and the red-envelope revenues have plummeted. Sadly, I can’t eat as much as I used to, but I can cook a lot better. Last week, I sent red envelopes to my nephews, our goddaughters, and a few other kids whom we’re so lucky to have in our lives. Letters, emails, and gifts have been dispatched to dear friends and loved ones, thanking them for blessing me; it’s considered right and good to pay your debts before the old year ends, and many of our debts aren’t monetary.

All week, I’ve been doing the traditional pre-New Year’s house cleaning, by which I mean I clean for five minutes and then rest for fifteen. I’ve tidied my study and sent reams of paper to the recycling bin. I threw away two pairs of old socks and one undershirt, which had a hole in one armpit big enough for Fozzie’s snout to fit through. I thought seriously about keeping it; my internal Marie Kondo asked sweetly, “Does it spark joy?” and I replied, “You know what sparks joy? Not spending money when I have 85% of a perfectly good undershirt.”

Chinese New Year is more complicated for adult me than childhood me, and not just because of all that needs to get done or my propensity to overthink everything. I have real, lingering questions about the traditions. Why do we even do what we do?

The American missionaries who converted my relatives in the early 20th century deserve some credit for my questioning—or some blame, depending on how you look at it. They arrived in China with both good news and bad. The good: Jesus loves you! The bad: Chinese customs are ungodly and heathen. (I wrote about this in regard to funeral practices after my maternal grandmother died a few years ago.)

The famed Baptist missionary Lottie Moon, who served in China from 1873 to 1912, had, for her time, relatively enlightened views of the people among whom she lived. In an 1887 Foreign Mission Journal dispatch, she wrote, “We should remember that the Chinese are not a small community of savages who gape in astonishment at Western civilization. On the contrary, China had a respectable civilization when our own ancestors had not emerged from barbarism.” On the other hand, that respectability only went so far; as Moon wrote the next year: “These heathen are not only without knowledge of the gospel, but their minds are full of superstitions and false notions.”

Okay, Lottie.

Such condemnations had real effects on everyday life. Even something as seemingly innocuous as the usual New Year’s greeting of 恭喜發財—“kung hei fat choy,” in my native Cantonese—came under indictment. To wish someone prosperity was deemed insufficiently Christian, because it emphasized material wealth. So the most devout converts, determined to demonstrate their piety, hewed to a more perfunctory 新年快樂 (“sun nien fai lok”)—simply, happy new year.

My forebears abandoned some traditions, like hanging red banners with lucky sayings to ward off evil spirits. But we kept others, including the big meals, obviously, because we know what’s good for us, as well as the distribution of red envelopes. Pious folks avoided envelopes with the Chinese characters for “fortune” or “luck.” Especially pious ones began using ones emblazoned with the word 恩—“grace.”

Please don’t misunderstand me: My point is not to demonize the missionaries or mock piety. They meant well, they did some good, and they also made some serious mistakes, as all humans do. And here’s the thing about traditions: They change. We choose what to continue and what to relegate to history. My ancestors had agency to decide for themselves—and we get to do the same now.

Here’s what I’ve been pondering: What if reclaiming tradition is part of being faithful? What if it doesn’t exist in tension with Christianity but resonates with it, and in finding new meaning, ancient practices gain fresh significance? What if reimagining these festivals is integral to understanding who I am and who I’m called to be?

Take the customary family-reunion dinner on New Year’s Eve. To bid the old year farewell and to greet the new one together reinforces belonging and mutuality. It embodies our belief that we don’t live this life alone. The presence of older generations—grandparents, great-grandparents—reminds us of all who came before, and the clamor of the kids shouts of what’s to come. Generations upon generations had likewise met around the table, decades and even centuries of gatherings testifying to our shared inheritance—stories and traditions, wisdom and resilience.

It’s not lost on me that this Sunday, some Protestant congregations will read the story of the Transfiguration. It’s weird and wild: Jesus climbs a mountain and hangs out with Moses and Elijah. Matthew’s Gospel has the fullest, most vexing account of the story, in which Jesus names Elijah’s earthly experience as foreshadowing of his own, as if to say that history repeats itself and others have walked these paths before us. Isn’t this a story about collective memory? Isn’t this a tale of ancestral strength?

Because we live nowhere near family, in recent years we’ve made New Year’s dinner a gathering of friends who are like family—a concept that would have been lost on my grandparents. This year, given COVID-19, it will just be the two of us and Fozzie. But those themes of resilience and perseverance seem especially relevant.

Some traditional aspects of the New Year still vex me. The Chinese zodiac still generates spiritual turbulence, given what I was taught as a child about astrology being demonic. Yet I also understand that my ancestors, in marking time with these twelve animals and in retelling the legends about how they came to hold such significance, were just doing something we try to do all the time: They were seeking to find order and meaning in the midst of life’s chaos.

To me, the twelve animals of the zodiac aren’t signs of fate marked out or symbols of fait accompli. Each has strengths and weaknesses, each its distinct character. There’s a way to imagine them as instructional: They point us to harmony. Cycling through the twelve, we’re reminded of seasonality, of the gifts of difference, of all that makes for abundant life. Where Rat was quick-witted and agile, Ox is patient and persistent; where Tiger is bold, even bossy, Rabbit is compassionate and earnest. Each brings something that helps make us whole.

I suppose that, no matter what culture we come from, it’s worthwhile to ask “Why?” (Don’t tell my parents I said that; when I was four or five, that was my response to pretty much everything that came out of their mouths, and I think they still haven’t recovered.) So often, we do what we do, we eat what we eat, and we celebrate what we celebrate—in church, at home, in broader society—because we tell ourselves that’s what we’ve always done. Sometimes there are good reasons to continue, but sometimes there are good reasons not to. To interrogate why we do what we do, to question tradition and heritage, to understand more deeply the reasons behind the rituals—this honors our ancestors in a way that rote refusal or customary imitation don’t.

Tonight, we will feast. Tomorrow, I’ll call my mom and dad, because, on the first day of the New Year, we pay respects to our parents; but I’ll also check in with friends who are like family, because they too have buoyed us and enriched our lives. On Saturday, I’ll text my aunt in Hong Kong, because on the second day, we honor our maternal relatives; but I’ll also send up prayers of gratitude for others who have showed me the strength and tenderness of mothering. And throughout, I will meditate on the gifts of the Ox—diligent and long-suffering, methodical and steady—and I will give thanks in advance for the year that is to come.

What I’m Cooking: There will be no big Chinese New Year’s dinner this year, no friends-who-are-like-family around our table. Also, I don’t want to be stupid: There’s only so much the two of us can eat. And for you Fozzie stans out there, no, I didn’t forget him; he’ll get something special.

I settled on a relatively austere menu—two appetizers and five main dishes.

Yesterday, I began making daikon-radish cakes, grating the daikon; chopping the shiitake mushrooms, the scallions, the dried scallop, the Chinese sausage; sifting in the rice flour; and steaming the resulting loaf, which now sits in the fridge, coming together and preparing to be sliced and pan-fried.

Tristan requested fried wonton. Anything golden is said to be auspicious for the coming months, and who doesn’t like some deep-fried goodness?

This morning, I poached a whole chicken, a symbol of unity and togetherness. (You can find the recipe for 白切雞—literally, white-cut chicken—here.) There will be fried tofu—they look like gold bars—which I’ll toss with mushrooms, because their roundness symbolize wholeness. Fish is a must on the table, because the word “fish” is a homophone for abundance; later today, I’ll head to the fishmonger to get some—maybe halibut, maybe snapper, definitely something more luxurious than we typically allow ourselves. I’ll stir-fry Chinese greens—specifically, yu choy, which sounds like the Cantonese words meaning “have vegetables” and speaks to the promise of a good harvest. And I got a duck breast from the butcher, which, if I render the skin properly, will double down on the golden theme; the leftovers will make outstanding fried rice.

It won’t be enough food, yet it will also be too much. I’m not sorry.

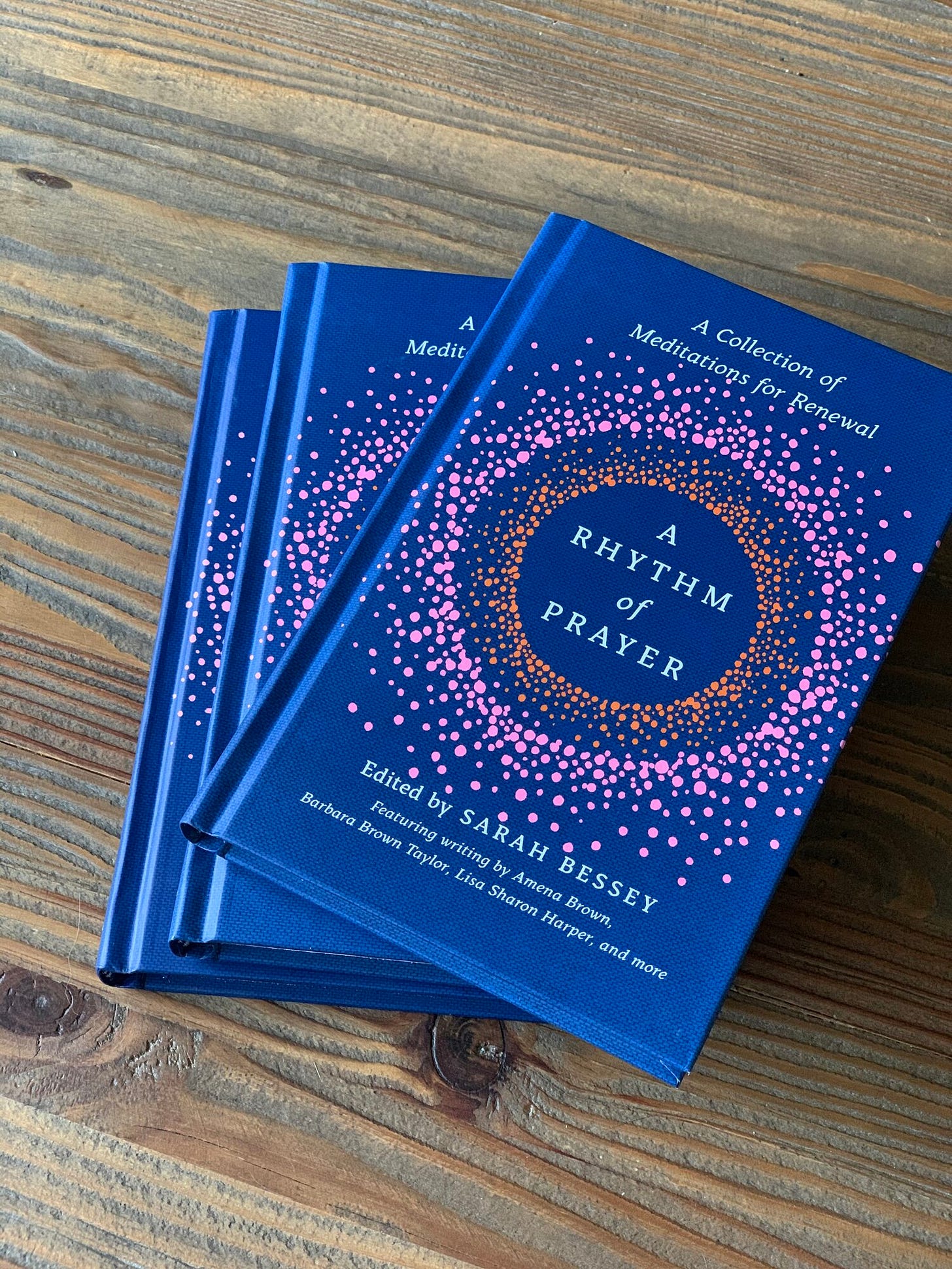

What I’m Reading: My dear friend Sarah Bessey released a new book on Tuesday! A Rhythm of Prayer includes her gorgeous voice and those of 23 other amazing writers, including Barbara Brown Taylor, Chanequa Walker-Barnes, and Nadia Bolz-Weber, all offering words and images that nourish us while point us beyond ourselves.

Prayer isn’t always easy for many of us nowadays. When I was a kid, prayer seemed blissfully simple. Then one day, an annoying church lady chided me: “God’s answer to prayer might not be your answer.” Lady, I knew that, but you didn’t have to say it.

Over the years, my prayers have become less lists of “I wants” and more a running conversation with God. There’s no real beginning. I don’t say “Father God” or “Lord Jesus” every half-sentence like in youth group; God knows who God is. Sometimes, I don’t have much to say, because I figure God already knows what I’m thinking and feeling anyway, so it’s more like a check-in, more an act of re-centering myself on God than one of reminding God about me. I’ve gotten better at lament too, because so much seems beyond me—or us.

Still, I often struggle with imagining what prayer could be—and that, perhaps, is A Rhythm of Prayer’s greatest gift. Some of the prayers in the book don’t seem much like prayers at all. But then I thought: Why not? For instance, Kaitlin Curtice offers a stirring poem built around images of a lantern and a wildflower. “Prayer is really tricky for me,” Kaitlin told me the other day when I asked why she wrote what she wrote. “Sometimes in my life, prayer is just better said as a poem. I grew up thinking that prayer was a very strict thing that you do during your quiet time or at meals. When I see prayer books, I still have that fear, that construction: Oh no! I don’t do prayer well!” When Sarah asked Kaitlin to contribute to the book, her thought was, “I don’t have a typical prayer. But I have a poem.”

Before I get back to the kitchen, let me wish you and yours a rich and joyous new year. May the coming of the Ox bring your soul steadiness even in the midst of turbulence, and may you find hope in its patient example and its steadfast presence. If you’re curious about this festival or if anything I wrote this week inspired a question, I’ll check in on the comments section in the coming days. Feel free to ask me anything!

I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

With gratitude and hope,

Jeff

Hello!! I've been one of those avid readers who looks forward to your newsletter, but haven't actually introduced myself. So wanting that to change :) I'm Rebekah, located in Seattle, and stumbled across your writings through Sarah Bessey. I have really loved your perspective, and as someone who has discovered my deep love of cooking food in the pandemic, it has been particularly fun to try your recipes. I hope someday to meet in person, but until then, hello!

I love reading about the red envelopes and the tradition of cleaning. Thank you for sharing your traditions with us. I’ve seen dragons associated with Chinese New Year-like in a parade. Is there a significance to that?