Hear Me Out

Some fragmented thoughts on the challenge of finding one's voice, shared vocabulary, seeking understanding, frozen bread, and cheesy music

Thursday, January 11

Grand Rapids, Mich.

For the first few weeks after Fozzie came to live with us in the spring of 2020, he didn’t bark once. He was the quietest dog I’d ever encountered.

Quiet, not silent: Sometimes he’d grunt. He sighed majestically, as if the weight of the entire world were on his terrier shoulders. As he spun to settle into bed, he’d whimper. When I scratched behind his ears or under his chin in just the right way, a rumble emerged from deep within. Do dogs purr? I don’t want to insult my dog by using a cat word, but it seemed like a dog purr.

Then one afternoon, early that growing season, we were in the community garden and the Fozz was on patrol, providing his contractually agreed protective services while I sowed seeds. A tiny, yappy dog wandered by, and Fozzie erupted, unleashing a full-throated artillery of barks.

He had found his voice.

What happened? I suspect that Fozzie began to feel safe. Our house had become his home; we were becoming his humans. In the garden, which we visited almost daily, he recognized our space; he never peed or pooped in our plot, always waiting until he was back on the grassy verge. In that emerging knowledge, in the accompanying security, perhaps he could be more himself. As his sense of belonging grew, he could bark freely—though, honestly, sometimes we wish he wouldn’t.

Over the past few years, I’ve been wrestling with what it means to find one’s own voice and how that happens.

As a reporter, I’ve learned that sometimes a person needs an invitation. A refrain I’ve heard in so many different contexts and so many different countries, in people’s offices and at their kitchen tables: “Nobody asked for my story before.”

Sometimes a person also needs space for trust to grow—and even in a short encounter, that trust-building matters so much. When I begin an interview, I often tuck my pen and notebook out of sight. My subject and I just chat. I might reveal something about myself as a bridge. Occasionally I’ll even let some silence linger. This is all strategic. To press too hard, too quickly, can diminish a sense of autonomy. Even the typically gregarious can struggle to summon the right words once they recognize that those words are being written down. Those whose stories haven’t been honored might rightly be skeptical that a stranger would do so. For many people—especially folks who haven’t been interviewed before and/or who might be shy—it feels risky to believe that I’ll fairly steward whatever they tell me.

A funny thing: Even as I was learning to help people find their voices, I was having my own trained out of me. At Time, I was taught to hew to house style, which governed a story’s structure as well as a dizzying array of commandments about diction, grammar, and punctuation. (There was a book.) The word “I” was to be used sparingly, if ever. If inserting oneself into the story was inescapable, a common practice was to refer awkwardly to “a reporter.” This irked one of my colleagues, an elegant wordsmith with a strong contrarian streak, who insisted on using the first person in every article he wrote; colleagues admired his prose but questioned his character.

Over time, the business changed, conventions shifted, and the personal essay came into vogue, even at top-tier news outlets. In reported pieces, writers became larger characters in their own narratives. Graham Dudman, a veteran editor at The Sun in London who then became a professor, spoke for many journalists of his generation when he urged restraint: “If a reporter litters their piece with a plague of ‘I this...’ and ‘I that...’ the reader will think, ‘I don’t care...’”

As I’ve struggled to find my own voice and as I’ve taken on different genres of writing—the sermon, for instance, as well as this newsletter—key questions have remained: How can a writer use the first person to create warmth and invitation? When is it hospitable, opening the possibility of shared experience and resonance with the reader? Where does it cross the line into self-absorption?

When I wrote Does Jesus Really Love Me? I cautiously offered a few tidbits of my own story. I’ve always been a private person, so this felt alien. Just as folks I interviewed might have worried about whether they’d be heard, I had so many questions about how my voice would be received. My goal was to divulge just enough to help the reader understand the personal stakes of my explorations of faith and sexuality, yet not so much that the story was all about me; call it the veneer of vulnerability.

In 2019, I wrestled with these challenges anew when I was asked to finish my friend Rachel’s incomplete book. With Wholehearted Faith, the assignment was to use the first person in an altogether different way: I had to find not my own voice but that of an Alabama-born white evangelical turned Episcopalian, a mom of two, a social-media enthusiast, a Crimson Tide fan—when I am none of those things.

It’s daunting to try to take on the voice of someone so different, someone so beloved. Some readers felt that I failed. In the online review that made me laugh the most—and yes, I am one of those writers who will always read all the reviews—the reader claimed that she liked all the parts that Rachel wrote and none of the ones that I was responsible for.

I wish that reader had provided examples, but her comment helped illuminate something important: Finding’s one voice matters, but it’s not enough. We tell stories because we want them to be heard. That relies on relational capital with one’s audience—trust, a willingness to listen, some kind of shared language, some sort of common understanding. I suspect that reader knew and trusted Rachel; she didn’t know or trust me.

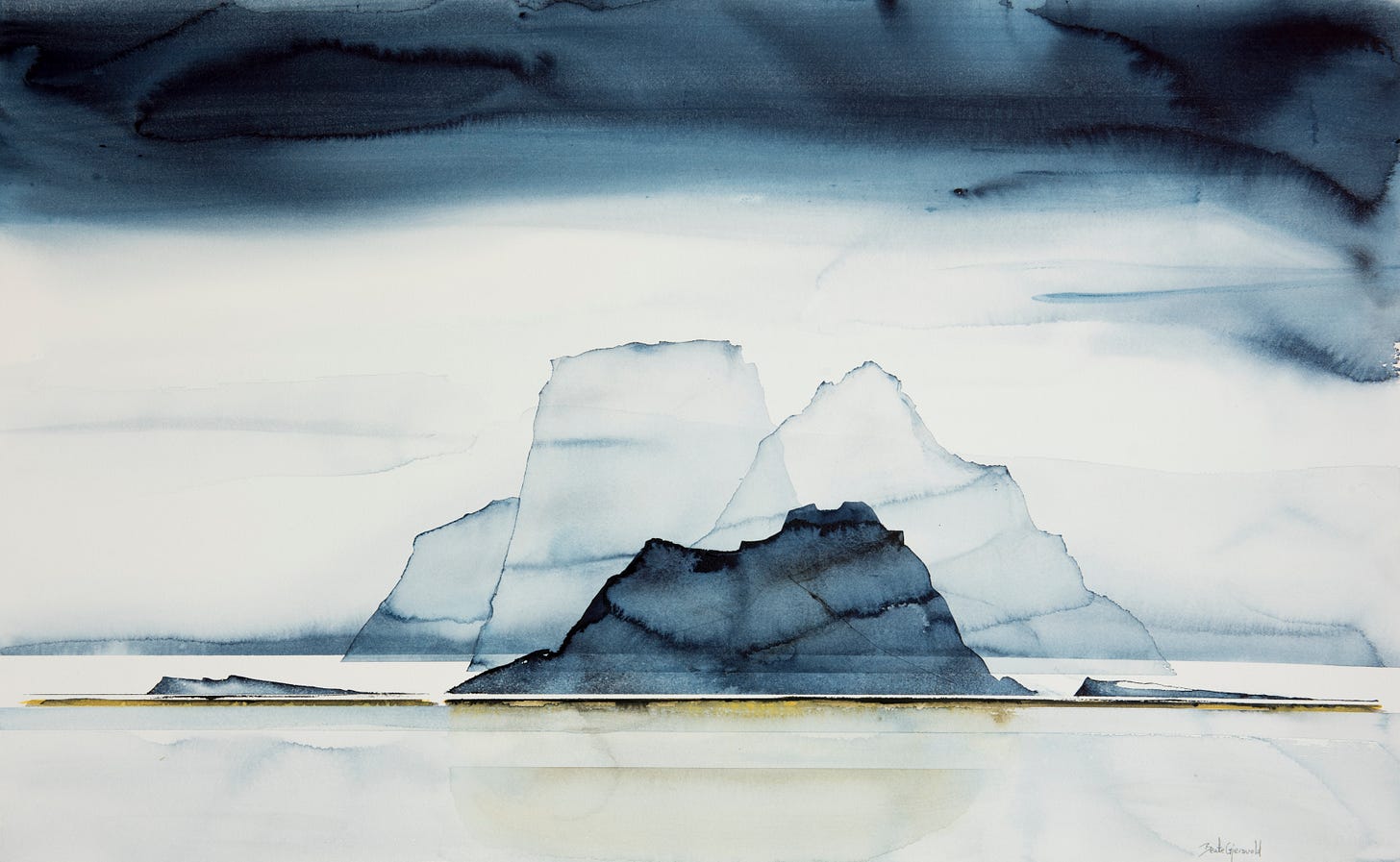

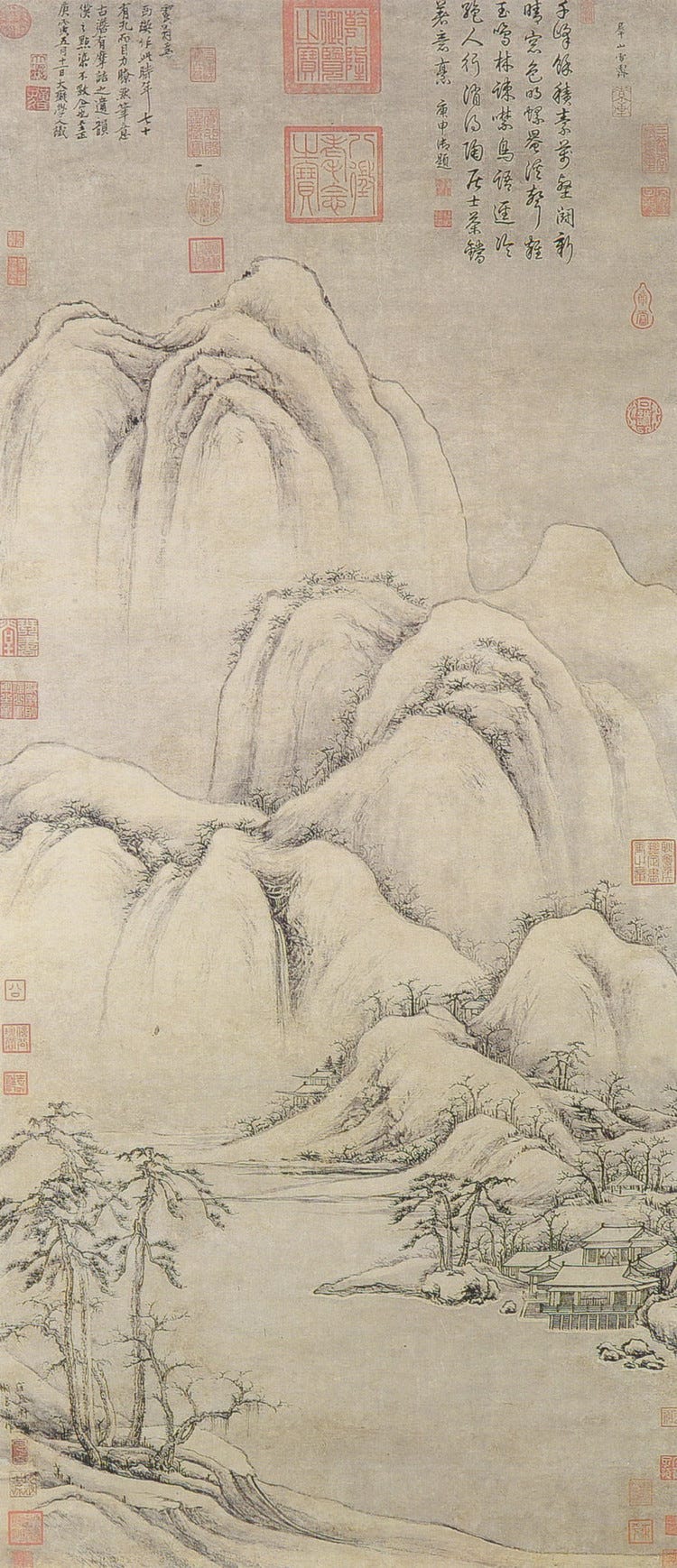

Indulge me a digression: In China, a school of poetry emerged about 1,300 years ago, during the Tang Dynasty, that emphasized order and austerity. Stanzas typically came in sets of four lines. Every other line had to rhyme. Each line of a poem had to contain the same number of characters—usually either five or seven, which, in Chinese, means either five or seven syllables, respectively.

The mandatory brevity made writing such poetry difficult. Chinese terms often contain multiple characters. What to do?

In the great Tang poet Meng Haoran’s “A Cold Evening’s Feast at Zhang Mingfu’s,” there’s a line that describes a beautiful lute player strumming a gorgeous tune. In an English rendering by Indiana University professor Robert Eno, the line reads: “Her jade fingers ring the lute-strings clear.” Eno tries to balance evocative imagery, textual fidelity, and clarity. But the original Chinese contains just five characters: 嬌 (delicate or tender), 絃 (string), 玉 (jade), 指 (finger), and 清 (clear).

How exactly does “delicate string jade finger clear” become “Her jade fingers ring the lute-strings clear” or, in another translator’s rendition, “The beautiful luthier plucks purity”? Turns out the original audience, steeped in a shared culture, could fill the white space between the characters. The combination of “finger” and “string” suggested a lute, and the word chosen to convey beauty signaled a feminine beauty, a fact underscored by the common use of jade as a metaphor for a woman’s skin. “Meng Haoran had no need to refer to the woman lutenist directly,” Eno writes. “His audience would see her there without fail.”

The key, of course, was that Meng’s target audience had a shared vocabulary. To find one’s voice without common language is to shout into a void that swallows the words without understanding them. Culture and context matter. So do values; if they’re not mutually accepted, at least they must be understood.

I suppose I’ve been thinking about finding one’s voice because it seems as if we are so often talking—or, on social media, shouting—past one another. It’s easier than ever to be in broadcast mode. What turns a piece or a post or an argument from a de-facto journal entry into communication? What keeps our emissions from being toxic? What enables a luthier’s song to be heard not as noise but as beautiful music?

In many ways, it’s wonderful that Fozzie has found his idiosyncratic voice. But sometimes he barks with what we suspect is an unintended ferocity. Finding one’s voice is important, but how does one then use it? I suspect that most of us want not just to be heard but also to be understood. Often, I find myself hoping that Fozzie will discover a different timbre, a less feverish pitch, a different tone.

Occasionally a passing dog will be undaunted by the Fozz’s seeming unwelcome. It will come up and greet him, and I see Fozzie immediately soften. What sounded to some like, “Go away!” might actually have been an urgent “I want you to notice me!” I wish I knew what enabled some dogs but not others—some people but not others—to listen for the thing behind the thing.

What I’m Cooking and Eating: Last week, we ate our way through a loaf of bread we brought back from the wonderful Rosendals Trädgård bakery in Stockholm. “But wait!” you might say. “Weren’t you in Stockholm in October?” Yes, we were—and one thing we’ve learned about good bread is that it travels well. Bread has become one of our favorite souvenirs.

We bought two unsliced loaves at Rosendals Trädgård on a Sunday, flew home the next day, immediately wrapped them well in plastic and foil, and popped them into the freezer. I’ve read that, if you intend only to make toast, it’s okay to slice bread before freezing; still, I think that risks drying it out too much. We prefer to keep the loaf whole. Then, when we’re ready to eat, I unwrap it, sprinkle the frozen loaf with some water, and pop it into a 350°F (180°C) oven for twenty or twenty-five minutes.

What I’m Listening to: I’ve never been ashamed of my soft spot for cheesy music. The Irish boy band Westlife absolutely used to be a fixture on my writing playlist. Lately, Lauren Daigle has made an unexpected appearance there. Her song “You Say” has accompanied me through so many moments when I’m struggling to put words on the page, not because I don’t have words but because I fear that they won’t matter. Daigle reminds me what, in my better moments, I believe—or want to believe.

If you’ve made it this far, I want to thank you for coming along for the journey. I’ve been using my weekly notes to you to play with different structures, different forms. Today’s essay is rooted in a traditional Chinese form of argumentation that doesn’t lay out a thesis statement, doesn’t offer proofs, doesn’t even make an argument. Instead, it circles around a topic, sometimes veering off in this direction or that, gathering data and making observations. It might conclude with clear resolution; it might not. Exploration is more the goal than pronouncement.

It would be a gift to me to know how well—or not!—this worked for you. I know that my writing often asks a lot of a reader. Usually, it’s not easy entertainment. Thoughts? Reflections? Constructive critique? All would be welcome.

Wherever you are, whatever is happening in your corner of the world, I hope you’ll be surprised by delight today.

With gratitude,

Jeff

Jeff, I greatly appreciate all that you write, no matter what style you choose to use to shape your story. How you wove Fozzie's voice and your voice and Rachel's voice was so beautiful. I have never met Rachel Held Evans, but in her writing, I see expansive faith which is accepting of complexity and multiple voices. This is the gift of your storytelling and writing also as you share others' stories and describe how we each find our way to live into gifts that God has given each of us. There will always be people who don't like or want to change something we give to the world. I believe as long as we are all humbly asking God to help us figure out what it is that God wants us to do and then being open to setting forth on the journey, then it is all good with God, which is all that really matters in the end. Thank you for the ways that you help all of us to experience God and find our voices.🙏❤

I like this structure. It invites us to consider something from many angles. Many things can be true, buy we are immersed in binary (shouty) thinking all the time. This type of writing feels contemplative. I like it.