Here Be Dragons

Some fragmented thoughts on the Lunar New Year, the misappropriation of the Chinese zodiac, dumplings, and an ancient legend about the loving dragons

Thursday, February 8

Grand Rapids, Mich.

Tomorrow night, we bid farewell to the rabbit and we greet the dragon. We’ll have a quiet Chinese New Year in our house this year. Last year, we celebrated with friends who are like family, filling a crowded table with all manner of delicacies. But this go-round, our schedule is more complicated. I’m heading to North Carolina to preach at Crosspointe this weekend, so a relatively simple New Year’s Eve dinner will suffice, and then I’ll spend the first of our dragon days on an airplane.

Maybe it’s better that way, given how grumpy I am as we welcome the dragon. For one thing, the rabbit didn’t live up to its billing as a bearer of peace and an avatar of calm. I suppose that’s why these creatures are symbols, not promises; humankind still has to choose to act accordingly. For another, I was on Instagram the other morning, and apparently the algorithm felt like messing with me. It deposited into my feed an assortment of posts by various self-help gurus and self-improvement influencers who have decided that the dragon has some personal message for them and their followers at this very moment, as if they were all named Daenerys Targaryen. As I scrolled through the comments, I saw so many like, “This is going to be a great year for me!” and “I feel this!” and “This is my year!” and even, in a special, cross-culturally appropriative moment, “Dragon is my spirit animal!”

Let me be clear: I have absolutely no problem with folks outside my culture learning about or appreciating Chinese tradition. Nor would I ever wish for anyone to feel less hope; especially nowadays, shouldn’t we summon it however we can? My people, too, are as guilty as anyone of misusing the zodiac. We’ll likely see it again in the near future: Because the dragon is traditionally (I’d say incorrectly) perceived as particularly auspicious, majority ethnic-Chinese countries—China, Taiwan, Singapore—have historically seen birth rates rise during the Year of the Dragon.

But the notion that any particular sign of the Chinese zodiac has any particular bearing on one’s own luck—in other words, that it has anything significant to say about individual success—is completely unmoored from the philosophical principles that inspired the zodiac’s creation and that have long undergirded Chinese society. Chinese culture has always emphasized collective harmony and prioritized communal good. It’s nonsensical to imagine that, every twelve years, you might have a good one and you’d be all set. None of this was intended to be about me or the singular you or any person in isolation. It has always been about us. It has always been about urging each of us—all of us—to be the best version of ourselves for the sake of the world.

There’s a likely apocryphal story about the late Chinese Communist premier Zhou Enlai and the Chinese zodiac. It’s said that he was in the midst of a well-lubricated dinner with some foreign visitors when one guest loudly ridiculed how Chinese children would be attached from birth to lowly animals like rats and pigs. “What was going on in the minds of your ancestors?” the man asked.

When the uproarious laughter around the table had died down, Zhou patiently laid out the logic of the zodiac. He didn’t see it as a handy tool for fortune-telling or some helpful guide to otherworldly luck. Instead, he understood it as ethically aspirational: The zodiac reflected how the ancients “expressed their hopes and wishes for the generations that came after them.”

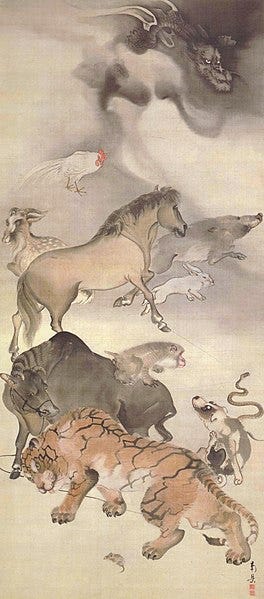

Zhou told his guests that the animals were ordered in meaningful pairs.

First came rat, representing wisdom, and ox, symbolizing diligence. “If there is wisdom but no diligence in applying it, it’s foolishness,” he said. “If there is diligence but no wisdom,” that, too, is foolishness.

Then came tiger, the picture of courage, and rabbit, an emblem of caution and restraint. “Without carefulness, courage becomes reckless,” Zhou said. “Without courage, carefulness becomes cowardice.”

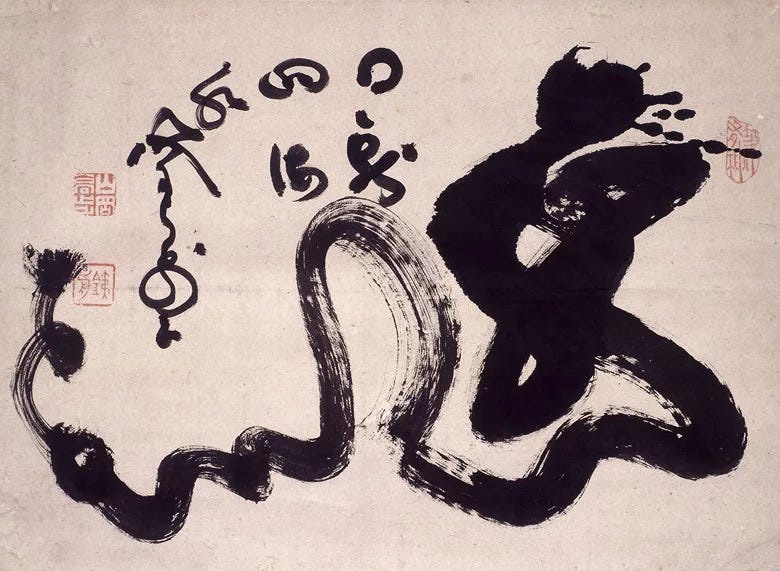

Next: dragon, an enduring embodiment of strength, and snake, known for its flexibility. “Strength without flexibility becomes brittle,” he continued. “Without strength, flexibility becomes meaningless.”

The fourth pair were horse, speedy and sure, and goat—some say sheep—which is recognized for consideration and compassion. “If a person only looks after himself as he pursues his goal and with no consideration for others, he will face obstacles from the people around him and he may not even be successful,” Zhou said. “If a person only looks after others and seek only to be amiable, he will not have a sense of direction.”

Then came the ever-adaptable monkey and the always reliable rooster. “If you have agility but no stability, your best plan will not come to pass,” he explained. “If you focus on having stability but refuse to change, you will not have a better future.”

Finally, the loyal dog and the good-natured pig: “If a person is loyal but does not have a good nature, he will blindly follow others. On the other hand, if he has a good nature but does not have loyalty, he will have no people and principles to guide him.”

Zhou explained that no one animal—and no one person—contained all that was needed for a strong family, a healthy society, or a fruitful world. “What our ancestors were pursuing was wisdom through integrity, harmony and balance. It’s never about an individual hope,” he said. “We need to live with integrity and in harmony with others and the environment.”

Wisdom, diligence, courage, caution, strength, flexibility, resolve, compassion, agility, steadiness, loyalty, character: We need all these virtues for human flourishing. None of us has it all. As we cycle through the diverse animals of the Chinese zodiac, we’re reminded of each creature’s strengths and superpowers but we ought not to ignore their weaknesses and vulnerabilities either. Nor should we forget that, even in the origin myths, it was in robust relationship that these creatures flourished and in selfish isolation that they failed.

Relationship is at the core of so much Chinese culture. Many families, particularly those from China’s north, have a tradition of making and feasting on jiaozi—steamed dumplings filled with pork and cabbage—on New Year’s Eve and into the early hours of New Year’s Day. The half-moon-shaped jiaozi resembled the silver ingots of ancient times, so they were considered lucky.

We are southerners, so jiaozi skills aren’t part of my family’s heritage. (Last year, our friends did help me make dozens of wonton.) Anyway, you can easily buy excellent frozen jiaozi in bulk nowadays; when I was a kid, my mom had a favorite shop in Oakland Chinatown where we’d get them frozen. But the old way was always to make them together, another part of the tradition that carries significance: Making dumplings, especially for a crowd, is a ton of work. So many members of a family, even those who rarely cooked, typically gathered in the kitchen to share the labor.

In the Chinese American culinary historian and cookbook author Grace Young’s seminal The Breath of a Wok, she visits with novelist Amy Tan as Tan and her sisters make jiaozi and reminisce about dumpling-making sessions of years past. Tan recalls the never-ending maternal commentary that any Chinese kid would recognize—her mom’s critiques about the thickness of the dough, the insufficiency of the filling (“too much cabbage,” “too watery”), the shape of the dumplings (“She accused my dumplings of having the shape of a ghost,” Tan said).

Tan tells Young that she and her sisters still gather to make dumplings on the anniversary of their mother’s death: “The idea is to make jiao-zi and then complain as we eat them that they are not nearly as good as Mom would have made.” As I read those words, I thought about how this tradition transmitted ancestral knowledge and reflected time-honored virtue. Once a year, at least, a family would engage in a communal act of feeding one another.

As I reflected on Tan’s familial memories as well as my own, I felt my lens widen too: None of this—not the meals, not the traditions, not the zodiac or any of its constituent animals—is about one moment or one person, one life or one year. It’s all about the fragile, fiercely beautiful whole.

One last story for you—one of my favorites from Chinese lore: Before the earth had rivers and lakes, four great dragons, named Black, Yellow, Long, and Pearl, lived in the sea. As they soared in the skies and played, they noticed that, on land, the crops had withered and the people were praying. The dragons flew to visit the Jade Emperor, who controlled the rains, and they begged him to let the rains come. He said he would, but he reneged on his promises.

Feeling deep compassion for the people, the dragons scooped water up in their mouths and spread it across the land. The Jade Emperor, enraged by the dragons’ initiative and feeling as if they had shamed him, entombed them within four mountains. Not to be outdone, the imprisoned dragons turned themselves into the great rivers of China: the Black Dragon (Amur), the Yellow, the Long (Yangtze), and the Pearl. Determined to bless the people in a lasting way, they chose to embody love.

May the stories of the dragon inspire you in the coming year. May you find harmony and eat many dumplings, and may the world hope in the possibility of life-changing love. From our home to yours, 新年快樂 (happy new year), 出入平安 (may peace mark your comings and goings), and 萬事如意 (may all go well with you).

In hope and with gratitude,

Jeff

I’m so grateful to you for sharing this. I’m Trinidadian, and my grandmother was Chinese (born of Chinese immigrants to Trinidad). Growing up, however, we didn’t celebrate Chinese holidays. This year, for whatever reason, I’ve been wanting to learn more about my Chinese heritage. Apocryphal or not, this explanation of the Chinese zodiac is deeply helpful. So thank you! ❤️

What wonderful stories explaining your heritages culture. Thank you for sharing and Happy New Year, may peace also mark your comings and goings, and all go well with you also.

Blessing on your trip to North Carolina.