Human Nature Is Bad

Some fragmented thoughts on not feeling Easter-y this year, the wisdom of Xunzi, petty men and gentlemen, the gift of ritual, and the recognition of breaking bread

April 18, 2025

Grand Rapids, Mich.

I don’t know how to get to Easter alleluias this year. I’m still stuck on last Sunday’s hosannas—and I mean that not in the laudatory sense but in the literal. “Hosanna” comes from the Hebrew הוֹשִׁיעָה נָּא: “Save us, please!”

You don’t need to be religious to believe that this world and this country could use a little salvation right about now.

People are being separated from their families and essentially sold into captivity. The current presidential administration is paying the government of El Salvador millions to imprison deportees, and its supporters pose for pictures in front of the imprisoned. And what of due process as well as checks and balances? “The government is asserting a right to stash away residents of this country in foreign prisons without the semblance of due process that is the foundation of our constitutional order. Further, it claims in essence that because it has rid itself of custody that there is nothing that can be done,” appeals-court judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III, a Reagan appointee, wrote. “"This should be shocking not only to judges, but to the intuitive sense of liberty that Americans far removed from courthouses still hold dear.”

Humanitarian aid has been slashed haphazardly by this administration. Youth who volunteer with community-based nonprofits and help with disaster relief through AmeriCorps have been sent home. People with HIV are being deprived of life-sustaining medication. The hungry will go unfed. The refugee, the widow, the orphan in so many poverty-stricken, war-torn lands—they will receive even less help.

Environmental protections are being loosened, scientific funding cut, and public health programs decimated, even as this administration eliminates support for museums and libraries, demeans the autistic, and rewrites history.

I see people I know gloating and celebrating all this, too, and I feel helpless to bridge the gulf of understanding between us. Anyway, empathy is seen as toxic now too.

There isn’t room in the newspapers for so much else that is happening: Two years into a bloody civil war in Sudan, hundreds of thousands of civilians who had already fled their homes are now being forced out of the refugee camps where they had sought shelter. There was a devastating earthquake in Myanmar less than a month ago; nearly 4,000 people died, those who survived have barely begun to rebuild, and relief efforts are faltering. On Palm Sunday, an Israeli missile strike hit Ahli Arab Hospital, a beacon of hope and healing that I’ve long supported. It was the last remaining fully functioning hospital in Gaza City, and now, its ICU and surgical facilities are rubble and debris.

Save us, please!

Save us from those who bring harm.

Save us, too, from ourselves.

--

We will go to church on Sunday—Tristan and I have already discussed it—but I’ve been in pre-dread. All week, I’ve been playing the previews in my head: the raucous pre-service chatter, the upbeat hymns, the jovial proclamations that “Christ is risen!”

I do not know how to celebrate the resurrection in a culture of death.

I do not know how to sing praise in the midst of so much that deserves mourning.

I do not know how to shout for joy when what feels right for this moment is a guttural cry of lament.

Which is why I was so surprised the other day to receive some venerable wisdom from the Chinese philosopher Xunzi, who lived, worked, and wrote several hundred years before Jesus.

Xunzi, which literally means “Master Xun,” grew up in a time of flourishing Confucian philosophy. China was then in its Warring States period; a constantly changing set of kings, dukes, and marquesses ruled over territories whose boundaries shifted like the tides. It should be no surprise, then, that Xunzi was largely preoccupied with questions of order, virtue, and wise governance.

I was drawn to his eponymous work—his collected writings are known as The Xunzi—because I came across one particular pullquote that intrigued me: “Human nature is detestable.”

Well, I thought, I like this guy.

Like his elder and fellow Confucian philosopher Mencius, Xunzi encouraged humanity to cultivate its moral goodness. But the two differed significantly on our starting point: Whereas Mencius thought people were born with an inherent benevolence, Xunzi argued that we are naturally egocentric, and the outcome of our unrestrained selfishness will be chaos. He was preoccupied with how to move us from self-absorbed independence to harmonious interdependence—and he was particularly concerned with the consequences for broader society of a lack of interest in such moral development. In such community, “what you hear will be trickery, deception, dishonesty, and fraud. What you see will be conduct that is dirty, arrogant, perverse, deviant, and greedy,” he writes. “Moreover, you will suffer punishment and execution, and you will not even realize it is upon you.”

We all have choices to make—something that Xunzi recognized all around him, as generals jockeyed for position and aristocrats arranged themselves in ever-changing series of alliances. He rejected the notion that those born into privilege had any advantage when it came to wisdom. “Someone says: sageliness is achieved through accumulation, but why is it that not all can accumulate thus? I say, they can do it, but they cannot be made to do it,” he argues in a chapter entitled “Human Nature Is Bad.” “Thus, the petty man can become a gentleman, but is not willing to become a gentleman. The gentleman can become a petty man, but is not willing to become a petty man. It has never been that the petty man and gentleman are incapable of becoming each other.”

But he wasn’t naive that the ramifications of a leader being a “petty man“—which is perhaps the most derisive term he uses. (Ancient Chinese philosophers might tend toward understatement in their prose.) “From ancient times down to the present, a case where having a gentleman in charge results in chaos is unheard of. There is a saying, ‘Order is born from the gentleman. Chaos is born from the petty man,’” Xunzi writes in a chapter about virtuous leadership called “The Rule of a True King.” “The judgments of a true king are such that those without virtue are not honored, those without ability are not given office, those without meritorious accomplishment are not rewarded, and those without criminal trespass are not punished.”

Do we not live in a time of petty men and pretenders?

--

Everything that Xunzi had to say, everything that I read of his, got me efficiently to Good Friday. But I was ready for that anyway—well acquainted with sorrow and no stranger to such grief. I still didn’t feel remotely ready for the quick two-step to Easter Sunday.

Then I came to some of what Xunzi had to say about tradition and ritual. To put it crudely: It’s not about one’s personal vibes. He reminded me that, while I might not know how to celebrate or sing praise or shout for joy, I can still choose to show up. What matters is being present to bear witness and allowing oneself to be moved. As Xunzi writes, “Ritual is a means of nurture.”

Xunzi analyzes collective rituals in his society and concludes that they are means of connection—to heaven and earth, to ancestors and wisdom. This profound sense of rootedness, he argues, is so important and can be so centering that “with ritual, all things can change yet not bring chaos.” It occurred to me as I read him, though, that he was not writing about rote reenactment or empty ceremonial performance. When Xunzi refers to “ritual,” he is calling for attention and reverence, across time and space and place. He’s also urging humility and discernment. “Will we follow foolish, ignorant, perverse men? Those who have died that morning they forget by that evening. If one gives way to this, then one will not even be as good as the birds and beasts,” he writes. “How could such people come together and live in groups without there being chaos?”

This sage, who lived before Easter was even a thing in the world, returned me to a truth about this most important of Christian occasions: Easter remains Easter however we’re feeling, regardless of what we do or don’t do, no matter one’s state of mind or condition of spirit. It’s ultimately not about feelings—mine or any other human’s—though, according to Xunzi, a time-honored ritual creates a container to hold them all.

For those of us who choose to believe the story, or even just try to believe the story, Easter is about what the One who embodied love came to do and what he was able to accomplish that nobody else could.

--

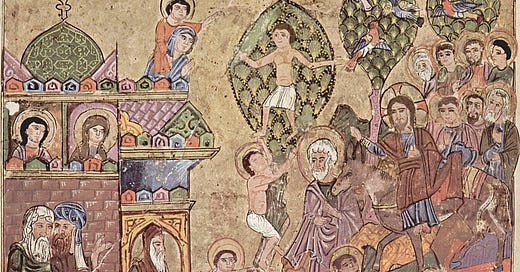

On that same day, the Gospel According to Luke tells us, two travelers walking the dusty road to Emmaus encountered another man. They talked with him and told him of their brokenheartedness: “We had hoped that he was the one...” All along the way, they kept talking, and this other man did some teaching. He even admonished them for being “slow of heart”—at which point I probably would have said, “Bye!”

But through all this, they kept walking with him, and they didn’t recognize him. When they got to their destination, they urged the man to sit for a meal with them. “When he was at the table with them, he took bread, blessed and broke it, and gave it to them,” the story says. “Then their eyes were opened, and they recognized him.”

The Greek verb that’s translated “recognized,” ἐπιγινώσκω (epiginosko), carries a prefix, epi-, that amplifies the knowing. This isn’t surface knowledge or shallow understanding; it’s rooted in experience and deepened by intimacy. And I love the description of the moment of recognition: Doesn’t it seem right that it’s in the act of being fed that the weary travelers feel the presence of the one who has meant so much to them?

So, on Sunday evening, we’ll turn to another time-honored ritual: We will welcome some friends to our table for Easter dinner. These are folks who have known us beyond the superficial level for some years, dear ones who will not shy from us bringing our whole selves to the table.

I’m making prime rib, and roasted potatoes, and some kind of vegetable—maybe Tristan’s mom’s creamed spinach? There will be bread to be broken too, in the form of Yorkshire puddings. And I hope that in being fed together, we, too, will recognize love and urged toward the goodness we so desperately need.

What I’m Listening to: Many people don’t know that Coldplay’s Chris Martin grew up in church. The most hymn-like Coldplay song, “When I Need a Friend,” has been a solace recently:

Holy, holy, dove descend

Soft and slowly

When I'm near the end

Holy, holy, dark defend

Shield me, shōld me

When I need a friend

Slowly, slowly, violence end

Love reign o'er me

When I need a friend

What I’m Growing: I spent some time out in the yard this week, mulching the garlic and planting some spinach and lettuce. The daffodils are still going, and our first tulips have opened up too. I’m always grateful for their reminder that winter’s cold and darkness are necessary for spring’s beauty and flourishing.

Let me ask that most dreaded of questions nowadays: How are you? What can I be remembering in my prayers on your behalf? What can I hold with you?

If you celebrate, may your Easter return you to goodness and fortify for what’s to come.

With gratitude and in hope,

Jeff

I was thinking about the disciples at the end of Mark, who ran away terrified and silent; and yet we have the gospel story. I think of that pair at Emmaus, dejected in their hopeless walk, and Jesus coming beside them to walk, reveal, encourage, nourish. I think of Christians in 536 AD (no sun for 18 mo). I’m so, so grateful for Easter when little else feels like it. A bright star peeking through dark clouds.

A blessed Good Friday to you, and a joyous, nourishing Easter!

Blessed Good Friday to you. Thank you for sharing this. Beyond his specific wisdom (Human nature *is* bad! And Petty men *do* bring chaos!) I find it so comforting to know that during previous falling empires, wars, and other devastations, people have been philosophizing, theologizing, praying, writing poetry and songs, planting gardens, making art, connecting with nature, etc etc. God really does move in and around and among and through us even in the worst of times. Maybe especially then. So, I will invest in the season's rituals in defiance of evil and hopefully be mended in some way. We are making a casserole and cooking a giant pile of bacon to take to the Easter brunch at church after service. 40% of our Episcopalian church parish lives alone, and many of them are elders (75+) who have no family near by; a lot of them don't drive anymore. It will be good to chant and sing pray and brunch with them.