"It Isn't Fair"

The testimonies of three American medical professionals who traveled to a devastated Gaza to volunteer

“We are all governed by chance,” Omar El Akkad writes in One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This. “We are all subjects of distance.”

Why do some children get to grow up hearing an explosion and running to the window, in delighted search of fireworks, while others have learned to run for cover, in fear of bombs? What did I do to deserve an adulthood filled with happy travel, planes taking me wherever I want to go, while others must crowd onto rickety boats in order to flee?

Chance, luck, fortune— maybe grace. I hesitate to use that word, though I did nothing to merit my relative safety. So many others have done nothing to deserve the calamity that has befallen them, and it feels wrong that the flip side of grace should be so cruel.

By chance, we are living in a time, too, when we’re inundated with images from all over. There’s so much video, such an onslaught of sight and sound, that we can grow numb to the reality that what we’re seeing and hearing might be the end of someone’s world. I want to turn it off—and I get to turn it off. For others, though, there is no off button. These are their lives.

In the hopes of remembering what’s at stake and for the sake of bridging the gulfs created by chance and distance, I spoke with three American medical professionals who have volunteered recently in Gaza. I wanted to hear their eyewitness accounts and to share them, so that we might hold them in our hearts. The least we can do is to bear witness to their stories and those of the people they met and served.

Fair warning: This won’t be an easy read. But as Kathleen Gallagher, a surgeon in Grand Forks, N.D., told me, “This is not about keeping people comfortable or making people happy. We have to sit with this: We have watched a genocide happen. We let it happen. And we have to do something.”

--

The news of a coming ceasefire broke the day before I spoke to Gallagher, who spent several weeks in Gaza last month, mostly at Nasser Hospital in Khan Younis. She’d been texting with friends there, and they were “cautiously optimistic,” she said. “Even a break in the bombing is something. They just need a break, quite frankly. But I’m hearing from folks on the ground that there’s still bombing. It hasn’t stopped yet.”

Gallagher served as a U.S. Army combat medic in both Iraq and Afghanistan. While doing her residency at Vanderbilt, she went to Ukraine three times. None of that compares to what she witnessed in Gaza.

She crossed into the territory in an armored convoy, through the Kissufim border checkpoint. “I still cannot find words to describe the devastation. There was nothing left standing between the border and Deir al-Balah. It’s just flat.” Then, surveying an area around Khan Younis that the Israeli military has designated a “red zone,” she said, “I was stunned to silence. The soldier in me wondered, What kind of firepower did they have to use, and with what frequency, to demolish an entire civilization?”

No less stunning: the warmth of the Gazans she met. A few days after her arrival, she’d already finished her shift when she got a call, at 10 p.m. “Doctor, doctor, there’s an emergency!” She pulled her scrubs back on and went in. It had been a ruse. Her surgical team had prepared the best welcome feast they could pull together—a spread of naan, a mix of canned tomato and canned tuna, boxed feta, and Spam that they’d fried. “They said they were so sorry this was all they had to offer, but it was lovely. We sat and we had this four-hour meal,” she said. “They wanted to tell their stories. And they wanted to know what life was like back home.”

The dinner was orchestrated by one of her Palestinian counterparts, an early-career surgeon whom she describes as “technically phenomenal. They don’t need us to teach them anything; they just need extra hands.” Not long before, he’d been at the hospital caring for patients when a bomb landed on his house, killing his father and brother. Another surgeon on the team was a widower; his wife and twin baby daughters had died in a strike.

Back home in North Dakota, Gallagher had heard people conflate Palestinians and Hamas. But the folks she met in Gaza “don’t support what happened on October 7th. I heard an immense amount of empathy and grief for the hostages and their families,” she said. “There’s also a lot of fear: If they speak out, will there be retaliation from Hamas?”

Again and again, Gallagher operated on patients shot while trying to get food at aid-distribution sites. She began to notice a pattern. The bullets’ trajectory through their bodies was downward. They had been shot from above.

Gallagher told me about one such patient, a 14-year-old who is his family’s last living male member. “The kiddo took it upon himself to go get food for his mother and sisters,” she said. “He’s now paraplegic. He was alive last time I checked, but he’s debilitated for life.”

The most horrifying loss Gallagher witnessed was the death of a six-month-old baby—“a beautiful, sweet little girl.” Her parents had brought her with them to an aid site, where they were trying to get food, when she was shot. Gallagher helped care for her immediately after her parents brought her into the E.R. and then sent her up to the pediatric surgeons. “They did everything they could, but she didn’t survive. She was so small. She was shot with a relatively large-caliber round through her abdomen. In my mind, there is no argument in the world that justifies that.”

What does success look like, in circumstances like these?

The 18-year-old brother of an employee at the guest house where Gallagher stayed came in with a gunshot wound to the chest. A bullet was lodged in his spine. Gallagher and her team managed to stop the bleeding and stabilize him. “When he woke up, he didn’t realize he was paralyzed,” she said. “That was a really devastating conversation to have.”

Over the subsequent days, as he began to process, his despondency grew: “He didn’t say it overtly but you could feel this sense of, ‘I wish you hadn’t saved me.’” Gallagher snuck him pieces of chocolate and challenged him to regular arm-wrestling matches—surreptitious physical therapy. By the time she left Gaza, “he was joking and talking about the future. He’s lucky that he has a very large family with a reasonable amount of resources.” Her biggest fear for him now is a pressure injury—say, a bedsore. “Several of our patients died of sepsis. The post-acute care system is gone. But he’s got the best chance of a functional, meaningful life.”

--

Oregon anesthesiologist Travis Meleen has done two stints in Gaza, one in June 2024 and another this past summer. “I often hear that a lot of people don’t believe what they’re seeing. They think the photos are staged, that babies aren’t starving, that people aren’t dying,” he said. “All the stuff you see is real—and it’s not only real but a poor representation of the reality, because it’s worse than what you’ve been told.”

He won’t soon forget an 11-year-old girl who arrived at the hospital while he was on duty last year. She could easily have been mistaken for a much younger child—sure signs of the malnutrition now common in Gaza. “Someone comes sprinting in, lays her down on the floor. She was bubbling blood out of her mouth, coughing and choking,” he said. “She was missing her jaw. Everything below her top teeth was just gone, blasted off in an explosion.”

To ease her breathing, Meleen cleared her airway of tissue and teeth, then he directed her to a nearby chair, to wait for a surgeon. Calmly and quietly, she sat, between two men. A few minutes later, when Meleen checked on her, he realized that the patients flanking the girl were both dead. “A girl with her jaw missing, and on either side of her, a dead man. She just waited until the surgeons were free,” he said. “Can you imagine an 11-year-old kid here doing that?”

Again and again, Palestinian resilience wowed Meleen. “They may not have a home anymore, and they may not have eaten for a day. But they’re still in medical school, or they’re still studying, or they’re still trying to teach their kids the alphabet,” he said. On the rare occasions he ventured out of the hospital, he quickly became a distraction from the grim reality. “Within five seconds, I’d have people wanting to shake my hand or ask about my tattoos or take a picture together. Life’s all still happening. People laugh, and people joke, just with a background of genocide.”

One of the closest friends Meleen made in Gaza was a fellow doctor. “Let’s call him Mohanned.”

Early in the war, it was still possible to pay to leave Gaza, a shady endeavor that involved paying between $5,000 and $7,000 per person to make it onto an exit list. Somehow, Mohanned scrounged enough to get his wife and kids to safety. But when he tried to leave, he was told the price had gone up to $10,000—an exorbitant amount given that wartime wages for government-employed doctors are about $30 a week. He had to stay and keep working.

Meleen and Mohanned spent many quiet moments chatting on the hospital balcony, talking about their families and telling each other funny stories to lighten the mood. “Everyone there is very depressed—but it isn’t even really depressed. It’s flat,” Meleen said. So much has happened that it’s as if the human spirit no longer can handle emotion. “How do you even react?”

Mohanned’s enduring hope surfaced in his steady conviction that he’d find a way to escape. Then, last week, Meleen got word that Mohanned had finally left Gaza. He’d gotten into a masters’ program overseas and navigated the bureaucratic maze required to matriculate. Though he neither wants nor needs another degree, he did want and need the path out.

Meleen was overjoyed and relieved. “Everyone you know over there is at high risk of dying every single day. I don’t have to worry: Is he alive? Is he dead? But I know it’s tough too. He has to leave everyone else he has known his whole life. There will be survivor’s guilt.”

--

Gallagher, Meleen, and Amanda Nasser, a nurse practitioner from San Diego who also returned from Gaza last month, all testified to their own survivor’s guilt. “I’m just very angry,” Nasser said. Since returning home, she has had nightmares. At work, she hides in the bathroom to cry. “I’ll be treating children, and they’ll remind me of the dead children on the floor of the hospital in Gaza who I’d tried to resuscitate.”

Nasser’s colleagues in Gaza have kept checking in on her, though they’re the ones living in a warzone. “That camaraderie,” she said, “has kept me afloat.”

So, too, has the enduring memory of the people she met. She thinks of Salha, an ebullient deaf woman whose brother was in the hospital, who was so excited to meet Nasser, to thank her for coming, to enfold her in a hug, to take a photo with her. Ahmad, too, who came in with a gunshot wound to his foot; “he had a smile on his face every day.” There was another Ahmad, a nurse at another hospital, who, before Nasser’s arrival in Gaza, had followed her on Instagram. After finishing a 24-hour shift at his own hospital, he took two buses to volunteer alongside Nasser at hers. He didn’t want to miss the chance to work together.

In Gaza, Nasser never slept more than four hours a night, running mainly on adrenaline, anger, and faith. “I grew up Christian. I consider myself faithful,” she said. “We believe God is protecting us, and somehow, everything is in the will of God. That gave me a sense of calmness. Almost.”

Though she’d previously volunteered in Mexico and in Greece, where she worked with refugees, Gaza felt more personal. Born and reared in San Diego, Nasser is Palestinian American; her dad is from Haifa, her mom from Kafr Yasif. As a child, Nasser spent summers on her grandfather’s farm, playing amidst the goats and the olive trees. Back home in California, her dad would often talk to her about Palestine and its struggles. When she was in elementary school, a Palestinian boy who had been shot in the eye came to stay with them while he received treatment. That set a template for her.

“I knew when I went to Gaza that I was only putting a band-aid on the situation,” she said. Her colleagues in Gaza told her not to overwork herself, not to be unrealistic, to recognize she wouldn’t be able to save everybody. Still, the questions nag at her. “Why are we on this earth? I question it. To see so much suffering? Why do some people suffer more than others? It isn’t fair.”

--

Meleen will head back to Gaza in a couple of weeks. Gallagher hopes to return early next year. Nasser took an unpaid leave to do her stint; if she can, she’ll go back, but in the meantime, she’s fundraising, through the Samir Foundation, to support doctors, nurses, and med students in Gaza.

If the ceasefire plan is fully implemented, humanitarian aid should ramp up quickly. The daily number of aid-carrying trucks allowed into Gaza by the Israeli government should at least to quintuple. Food, tents, medical supplies—all should flow in more easily. Yet it will take immense resources to begin repairing the damage that has been done—and it will require the ceasefire to hold. “The people I know there are more excited this time, and more hopeful,” Gallagher said. “But we’ve been here before.”

According to the Palestinian Ministry of Health, more than 67,000 people have died in Gaza since the war began; the U.N. has said that this is likely a massive undercount of the actual toll. Tens of thousands of children are now suffering from acute malnutrition. Reconstruction will cost upwards of $80 billion, according to the most recent estimates.

Meleen, Gallagher, and Nasser all told me that those of us who can’t go still have a part to play in securing peace and helping to bring healing. We can call our members of Congress and encourage them to use their power. We can share stories and humanize the news. We can give generously.

“We’ve heard the words, ‘Never again!’ for decades,” Nasser said. “Do we mean them? My dad said, Any child is a child of God. Anyone who is suffering, it’s our responsibility to take care of them.”

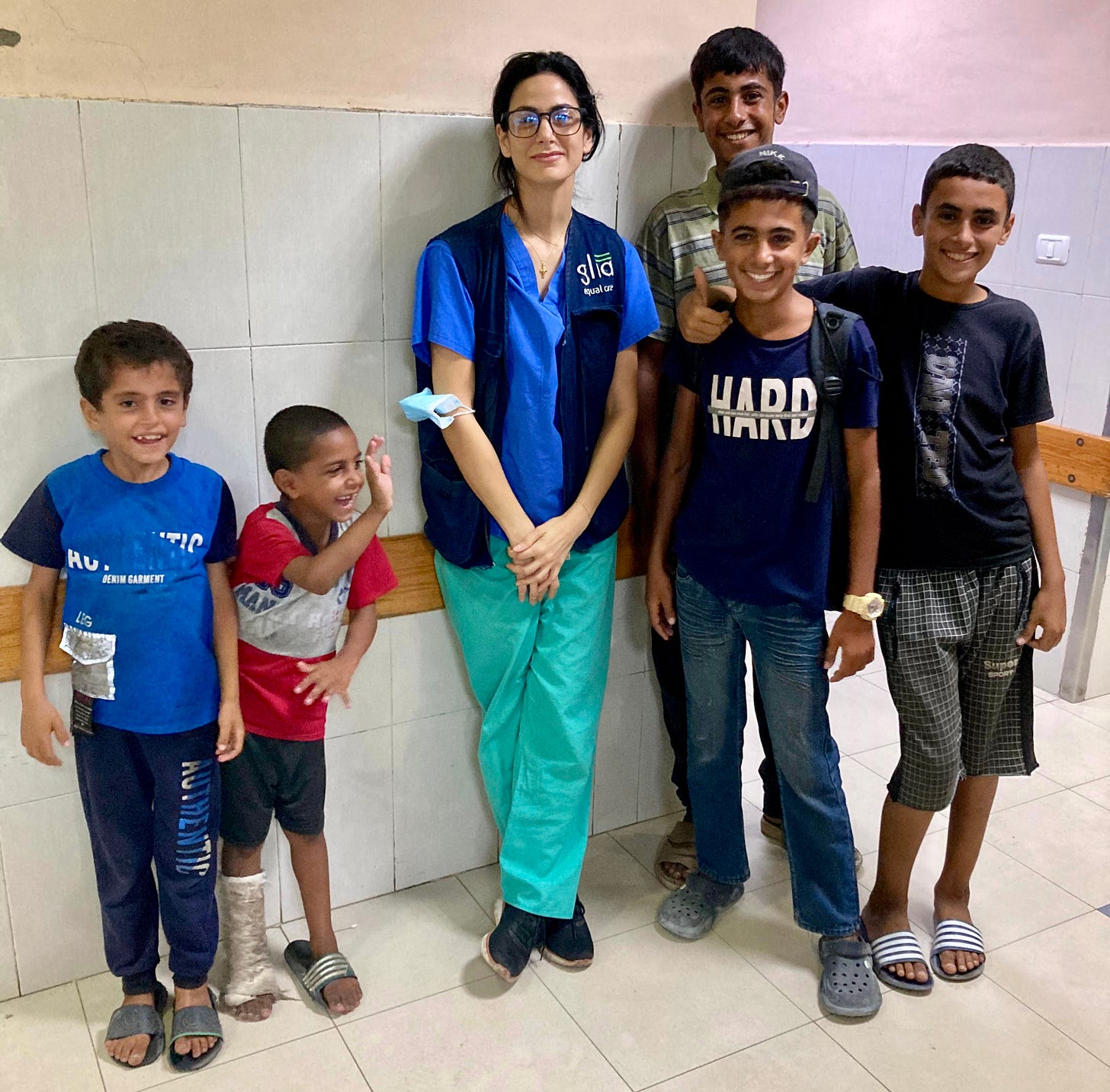

My deep gratitude to Kathleen Gallagher, Travis Meleen, and Amanda Nasser for sharing their stories. Gallagher traveled to Gaza with MedGlobal. Meleen and Nasser volunteered with Glia. The Samir Foundation works to bolster Gaza’s healthcare infrastructure through direct support of medical students. I also continue to support Ahli Arab Hospital in Gaza City.

That’s all for this week. I have no other words.

Yours,

Jeff

Thanks for carrying these stories forward. May we all work to keep from becoming too numb to care and to share in this horrendous pain.

By our testimony we bring the truth to light. Thank you for sharing theirs🥺