Justice, and Only Justice

Some fragmented thoughts on Ruth Bader Ginsburg, unlikely friendships, flowers, Sunday dinner, and enduring love

The 113th Day after Coronatide*

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Hello, dear reader.

We’re not even 3/4 of the way through 2020, and I feel as if this one year has already encompassed a decade’s worth of grief, anxiety, and loss.

Because of the odd cultural bubble in which I was reared, I rarely feel the deaths of prominent people as others in American society do. I probably haven’t seen their movies, I probably haven’t watched them perform, and I definitely don’t know their songs by heart. I’ll never forget, for instance, after Prince died, expressions of profound grief blanketed social media, his greatest hits were all over the news, and I kept saying to Tristan, much to his puzzlement, “That was a Prince song?”

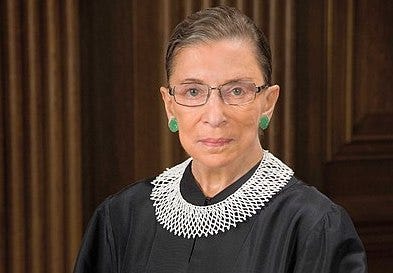

Ruth Bader Ginsburg was different.

I never met her. I have little in common with her. I don’t know much about law; the closest I came to law school was the LSAT-prep book my mom—so full of hope!—gave me when I was a senior in college, which I never opened. But I have learned to recognize the story of someone who perseveres through a system not built to honor the “other” and who then uses her power for good.

Ginsburg once recalled a family road trip when she was a child. As the Baders drove through rural Pennsylvania, she spotted a roadside sign: “No dogs or Jews allowed.” She was also old enough during World War II to absorb some of its brutal, hateful realities. “The sense of being an outsider—of being one of the people who had suffered oppression for no sensible reason... it’s the sense of being part of a minority,” she said in a 2018 interview with The Forward. ”It makes you more empathetic to other people who are not insiders, who are outsiders.”

As a lawyer, a professor, and a judge, Ginsburg consistently supported the rights and dignity of those considered less-than or at greater risk of discrimination in society. She consistently advocated for women’s equality in every sector of work and life. She wrote a scathing dissent to the Court’s 2013 decision, in Shelby County v. Holder, to invalidate a key part of the Voting Rights Act; she described it as “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” And in the landmark 1999 decision in Olmsted v. L.C. that rejected the forced institutionalization of some disabled people, she said that the overturned law “perpetuates unwarranted assumptions that the persons... are incapable or unworthy of participating in community life.”

Community life mattered deeply to Ginsburg. One of her most inspiring qualities was her ability to have lasting relationships with people very different from her—and it grieves me that this counts as noteworthy. Over the past week, various testimonials have appeared, online and off, about Ginsburg’s care and loyalty, which transcended ideology or ethnicity, social location or background. During her 1993 Supreme Court confirmation hearings, Ginsburg recalled a college professor of hers named Robert Cushman, who suggested that she read far beyond her areas of comfort or even personal interest. “A great teacher forced me to think about the times in which we were living,” she recalled, “when I really didn’t want to.”

The best teachers, the most valuable friends, the most treasured and unexpected relationships do just that—they compel us to engage with the world around us, even when that’s not our inclination.

Of course there was her well-known friendship with Justice Antonin Scalia. She was Jewish, he Catholic; she was a Democrat, he a Republican; she a liberal, he a conservative; she believed in a living Constitution whose meaning can change over time, he a strict originalist. Yet they forged a mutual affection. She’d encourage him—always privately—to temper the fierce tone of his opinions, and he’d help her—always privately—correct any grammatical errors in her writing.

The allegiance was commemorated musically in a modern opera by Derrick Wang called Scalia/Ginsburg, in which her character has some lines that delighted her and that she quoted afterward to capture their friendship: “He’s not my enemy. He’s my dear friend... We are different, we are one: different in our approach to reading legal texts, but one in our reverence for the Constitution and for the institution we serve.” After Scalia died, she wrote in her tribute: “We were best buddies,” as if they were two kids living down the block from one another.

There were other, less publicized friendships too.

There was Judith Richards, another Republican and a minister’s kid from small-town Ohio who came up in the world of law around the same time as Ginsburg did.

There was Jason Wiesenfeld, whose mother, Paula, had died in childbirth. In 1975, Ginsburg successfully argued a case before the U.S. Supreme Court on behalf of Paula’s widower, Stephen, who had been denied the Social Security survivors’ benefits because the law only provided for widows, not widowers. Ginsburg stayed in touch with the Wiesenfelds. In 1998, she officiated at Jason’s wedding, and in 2014, she did so again when Stephen Wiesenfeld remarried.

There was Eric Motley, a vice president of the Aspen Institute, an African American son of the rural South, and a former aide in George W. Bush’s administration. Motley wrote a stirring New York Times piece about his friendship with Ginsburg. I can’t imagine it would have been easy to write, not least of all because, the day Ginsburg died, she had been scheduled to officiate at Motley’s wedding.

What brought Motley and Ginsburg together years before was Bach’s Goldberg Variations, and perhaps there’s a lesson in that. The thirty variations that form the whole of the Goldberg suite vary tremendously—some fast, some slow, a canon here, a gigue there. It isn’t the melody that coheres them—Bach didn’t go for anything so obvious. Instead, it’s a bass line, a pattern of notes that shows up over and over, providing the variations with a common grounding.

As I consider all of us who are struggling with divides—divides in the country, divides in the church, divides in our various circles of community, divides in our families—it occurs to me that Ginsburg’s life and the Goldberg Variations both remind us to look carefully for what we share. How is it that Ginsburg and these others, so vastly different in background and philosophy, managed not only to co-exist but also to become friends? What might we learn from their ability not just to tolerate one another but also to enjoy one another and to serve one another?

In her court chambers, Ginsburg had multiple artworks featuring Hebrew words: תִּרְדֹּ֑ף צֶ֥דֶק צֶ֖דֶק. It’s a snippet from Deuteronomy 16:20: “Justice, and only justice, you shall pursue.” One might disagree with some of her interpretations, but nobody can question that this was the desire of her heart. “The demand for justice runs through the entirety of Jewish tradition,” she writes in My Own Words, her 2016 autobiography. Her hope for her service on the Court: “To remain steadfast in service of that demand.”

Already, politicians are talking about erecting statues of Ginsburg and naming things after Ginsburg, but I’m not much for those kinds of tributes. A far better honor would be to learn from how she lived her life and especially how she treated others. “People who have known discrimination are bound to be sympathetic to discrimination encountered by others,” Ginsburg said during her 1993 hearings, “because they understand how it feels to be exposed to disadvantageous treatment for reasons that have nothing to do with one’s ability, or the contributions one can make to society.”

I long for the day when our imagination and empathy, individual and collective, are so expansive that we need not be discriminated against to understand the injustice and the toll of discrimination. As it is said in Jewish tradition, may Ginsburg’s memory be a blessing. And may her memory and her example be an inspiration to us as well.

What I’m Growing: Not much news to report from my garden this week. So in other garden news: One of the pretentious dreams I’ve always had is that I someday want to have a weekly flower budget. That hasn’t happened—they still feel like an indulgence, though less so this year, because our rental has a great hydrangea out front. Anyway, on Saturday morning, I followed a friend’s wise advice and went to Three Acre Farm, about twenty minutes away from our house, where Lori Hernandez and her family grow beautiful flowers. It was their last day of u-pick—and I really detest the “u,” but that’s how they write it. For just $20, I filled one of their pitchers, and when I got home, it was enough to make five arrangements.

What I’m Cooking: With Tristan away, it’s been more of a chore—but also a discipline!—to cook for myself. For me, meals are meant to be shared; togetherness turns food from mere calories to true sustenance. Usually, I try to make us a nicer-than-a-usual-night Sunday dinner. So on Saturday, I went to the farmers’ market with that in mind. A goat farmer had goat meat on sale, so I bought a shoulder steak. Farmer Bob had lovely purple potatoes. I already had chard in the fridge. I sliced the potatoes and threw them into a pan with duck fat, I did a quick marinade (garlic, lemon, rosemary) on the goat and seared it on both sides, and then I sautéed the chard with some garlic. It was fine, but it would have been better with Tristan.

What I’m Reading: Ugh. Can we not talk about that this week? I feel like my attention these days has the lifespan of a mayfly.

What I’m Listening to: Tuesday was our eighth wedding anniversary—and the first we’ve spent apart, because Tristan is in Texas, visiting his family. Perhaps it was apt that, as I did research for this week’s newsletter, I found a recording on the NPR website of Ruth Bader Ginsburg reading the last letter her husband of 56 years, Marty Ginsburg, wrote to her before he died in 2010. I listened to it. And then I listened to it again. And I prayed a selfish prayer: that Tristan and I might have many more years together, marked by the kind of love that infuses both the letter and the reading of it.

Finally, the Evolving Faith conference is happening next Friday and Saturday! It’s an online conference, yes, but many of the speakers and I will be coming to you from a professionally cleaned, safe-as-possible studio in Atlanta. I know some of you are already joining us, but if you haven’t got a ticket yet, why not? If it’s a financial thing, please email me (jeff@byjeffchu.com) and tell me a bit about what’s going on. I’ll invite five readers to join as my personal guests. If it’s not a financial thing, I hope you’ll go to evolvingfaith.com/register and sign up. I am super-excited about our artists and speakers, including Barbara Brown Taylor, Amy-Jill Levine, Sherrilyn Ifill, and so many other tremendous and wonderful human beings.

That’s it for this week. Next week, I will finally write you from somewhere other than Grand Rapids, because I’ll be in Georgia, constantly checking my mask, sanitizing my hands, and prepping for Evolving Faith. I can barely believe it.

Yours,

Jeff

*I’m counting my days from June 1, when my governor, Gretchen Whitmer, lifted Michigan’s stay-at-home order. More than 200,000 people have died so far in the U.S. alone. Please continue to wear your masks and stay safe.