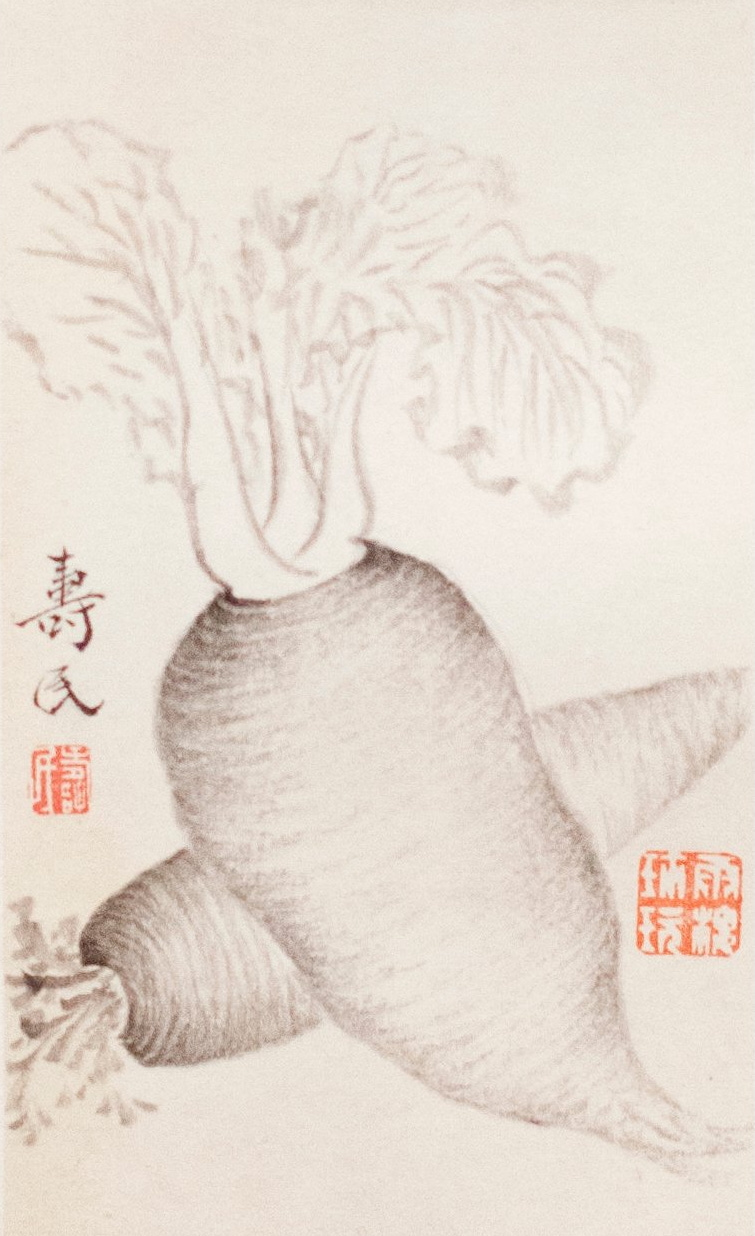

Lent I: Bitter

Some fragmented thoughts on daikon cakes, shades of flavor, translation difficulties, and the catalytic grace of community

March 6, 2025

Grand Rapids, Mich.

Daikon radish is not the most aesthetically pleasing of vegetables. It looks something like a fat, albino carrot. But it’s the essential ingredient in lo bak go, a steamed, then pan-fried staple of the dim sum table that is often confusingly called turnip cake, even though it contains no turnip at all.

My mom rarely made lo bak go at home because it’s somewhat labor-intensive and there’s really no way to rush it. Mostly, we’d have it when we went out for dim sum. Lo bak go always tells you something about a restaurant. You can tell if they’re cheaping out by using too little radish and too much rice flour. Poorly made cakes lack the radish’s mildly bitter flavor. All you can taste is sausage, shrimp, and— if they’re especially bad—the oil in which the cakes were fried. A lazy, rushed kitchen will put out lo bak go that has insufficient browning and no contrast in texture. If we’re at dim sum and we order radish cake, I like to watch for my mom’s reaction: She’ll wrinkle her nose if there’s insufficient radish or nod in satisfaction if there is enough.

As a kid, I didn’t love lo bak go that was properly made. The ones that were overly heavy on rice flour were just bundles of starchy goodness, vehicles for salt and fat and umami. If they were well crisped, even overly so, I could eat them.

It was the bitterness that bothered me. But, like so much else, the palate changes over time. My taste buds have matured, gaining the ability to appreciate flavors that, when I was younger, just tasted foul. The daikon’s bitter tinge didn’t change. My ability to understand it as something delicious, something worthwhile, something good, did.

In Singapore earlier this year, we were served a dish of bitter melon with pork. I pre-grimaced, bracing for a tongue-turning bitterness. It never came.

I can’t easily explain what was there instead—something surprisingly pleasant!—because English lacks adequate vocabulary to describe the different kinds of bitterness. Set against the umami of the marinated pork, the savory gravy, and my perhaps-unfair expectations, the bitter melon was almost bright.

It’s hard to say why I appreciated this bitter melon in a way I never had before. Perhaps it’s because the bitterness didn’t overwhelm; it was not too much, but just enough to say, “Hey, there’s something different happening here.” Maybe it was because, somehow, I was able to pay attention, at once, to what was familiar and comforting as well as to what was strange.

I can’t say I loved the bitterness. But it woke me up.

--

Cantonese has multiple words to describe bitter flavors.

Some people say that 澀 (“geep,” with a hard g, rhymes with “keep”) is one. More properly, though, 澀 is a feeling, not a flavor. 澀 is the sort of astringency that dries the palate and makes your mouth pucker.

苦 (pronounced “fu,” with a rising tone) is the most common kind of bitterness. Bitter melon is called 苦瓜 (“fu gua”)—literally, “bitter melon.” 苦茶 (“fu cha”)— bitter tea— is a catch-all term for the medicinal infusions brewed up at the Chinese apothecary. 苦 is bitterness that clings to the palate, often until it’s chased away by something else.

As a kid, if I ate something even remotely bitter, I’d grimace and exclaim, “苦!”

Usually, my grandmother would sigh and gently chide me: “甘!”

甘 (“gum”) has no precise translation in English. Some people have described it as a bitter start with a sweet finish. That doesn’t seem quite right to me, but it hints at an important truth: The bitterness of 甘 doesn’t linger. It’s clarifying, not overwhelming. In its wake, other flavors taste somehow more vibrant.

甘 is a bitterness that doesn’t smother. It never overstays its welcome. It brings a change of perspective.

--

My grandmother occasionally told me war stories. Because she was devoutly Baptist, though, I suppose the correct genre would be “testimony.”

She was born in a time of tumult, in 1912, the year of the abdication of China’s last emperor and the rise of a fragile republic. As for so many of us, though, it was her twenties and thirties that most shaped her. That was a season of war. In the early 1940s, the Japanese moved across southern China, occupying Hong Kong and sending her, my grandfather, their young children, and thousands upon thousands of other people, fleeing as refugees.

After the war, she lived on poverty’s edge, as a schoolteacher and a pastor’s wife and a mother of six. She and my grandfather immigrated to the U.S. in 1969, and without adequate English, the only work she could get was in a California sweatshop. After she retired, she spent the rest of her life caring for my stroke-disabled grandfather.

Evidence of what she’d lived through was scattered all over her apartment. Under the bathroom sink, she kept gallon milk jugs full of pennies. Stashed under the bottom drawer of her desk was a thick stack of twenty-dollar bills, bound by rubber bands. After she died, we found yet more twenties, hidden at the bottom of a box of yarn. War taught her always to be ready.

“Bitter” is the last word I’d use to describe my grandmother. Unflappable, doughty, resolute, encouraging—yes. Prayerful, hardworking, occasionally sad, hopeful but not optimistic—absolutely.

Bitter? Never.

Always, she’d contextualize her life in the light of God’s goodness and provision. Always, she’d explain how, amidst suffering, she found mercy and grace. Always, she pointed me back to the psalms, which she read daily.

It wasn’t until adulthood that I understood what she was trying to do for my benefit: Her stories were the equivalent of a well-prepared dish of bitter melon with pork.

苦 means “bitterness,” yes, but not just in a culinary sense. It’s also a word for hardship and suffering. In Buddhist-inflected Chinese thought, a virtuous human is taught to 吃苦—literally, “eat bitterness.”

This has frequently been interpreted as an instruction to persevere through pain without complaint. After all, suffering is inevitable, but to protest it is a choice. In the cultural framework in which I was reared, one’s personal feelings were real and valid, but they were also properly subordinated to the greater good, which was rarely, if ever, helped by one’s moaning and groaning.

Perhaps, though, there’s a way to extend the metaphor of eating bitterness in a way that feels like progression toward resolution: After you eat, you digest. A healthy body breaks down what’s eaten into its constituent parts. It takes what’s useful and nutritious and delivers it where it needs to go. Then it takes what is not useful and ejects it as waste.

I wonder whether eating bitterness could be understood—and experienced— not simply as an instruction not to express your pain or angst but rather as a healthy and even natural picture of how to process it. In that way, it’s both a coping mechanism and a healing process: a means of taking the suffering that will inevitably come, extracting what’s beneficial, and expelling what isn’t.

Even here, the digestive system offers some help. The process of breaking down the food we consume is not something we do on our own. It happens in largely unseen community, with the body and microflora working in strange and symbiotic partnership. It takes time. It can’t be hurried.

And what if “eating bitterness” were rendered not as 吃苦—not a bitterness that overwhelms, not a bitterness that lingers—but rather as 吃甘— a bitterness that clarifies and catalyzes? My Cantonese isn’t good enough to know if that’s grammatically correct. But theologically and philosophically, it feels right. In the context of the garden, too, it seems apt. When I first planted daikon at the farm, it bolted. But then I received the consolation prize of delicate, flavorful daikon blossoms. Decay and even death are never the end of the story.

--

I made daikon cakes on Tuesday, when some friends came over for dinner. Every radish is different, and daikon harvested in the wintertime tends to be sweeter. As I cooked, I remembered my ancestors, recalled my grandmother’s ardent prayers, and heard the echoes of my mom issuing me instructions in the kitchen.

Then, as we ate, we shared stories—ours, of our travels, and our friends’, of a new grandchild—and we talked about the state of the country and the world. Our conversation was much like the daikon cakes that we were eating: a bit salty and a bit spicy, rich and savory, with texture and layers. There was just the occasional hint of bitter—I’ll let you imagine what we might have been discussing—but never the kind that lingered.

I had almost forgotten that it was the night before Lent, until the topic of Lenten disciplines came up, and we briefly discussed whether we were giving anything up. So often, I have perceived this season as one of solitary contemplation, abstention, or discipline. But as we sat and talked into the night, it struck me that gathering intentionally might be the wiser thing for me this year.

In the company of those I trust, respect, and love, I feel lighter and freer, more ready to hold the bitterness of the world and more open to hope. Surely we are better together. We were never meant to do this alone.

[The italicized portions of the above essay are adapted excerpts from Good Soil: The Education of an Accidental Farmhand, which will be published by Convergent/Penguin Random House on March 25.]

Here’s my recipe for daikon cake. Some supermarkets carry daikon. You can always find them at Asian grocers. This recipe is versatile. If I have no Chinese sausage on hand, I might fry some bacon and crumble it up. I have dried shrimp, because my mom recently sent some; if you don’t and can’t access an Asian grocery store, or if dried shrimp sound gross to you, leave it out. If you’re vegetarian, making this just with mushrooms and green onions works well too.

Lo Bak Go (Daikon Cakes)

20 oz. daikon, grated

1 c water

1 c rice flour

1 T cornstarch

1/2 t salt

1/2 t sugar

1/2 t white pepper

2 T oil

1 T dried shrimp

1 scallion, chopped finely

3-5 dried shiitake mushrooms, soaked and chopped

1 link of Chinese sausage, diced

Simmer the grated turnip and the water for 10 minutes, stirring from time to time. Remove from heat and transfer to a large mixing bowl. Add the rice flour, cornstarch, and seasonings, and mix well.

Pan-fry the dried shrimp, scallion, mushroom, and sausage in the oil for about five minutes. Then add it to the bowl and mix well to combine. Let sit for 15 minutes.

Grease a loaf pan and pour the filling in. Set in a steamer and steam for 45-50 minutes. Cool for at least 30 minutes—an hour is better, or even overnight—covered, in the fridge, to set.

Cut into half-inch-think slices. Pan-fry in hot oil until golden brown on both sides. Serve with oyster sauce or, if you like spice, chili-garlic sauce or chili oil.

Last week, I asked what in your life might be giving you hope. So many people responded. I love how we pointed one another to the chickens in the backyard, and to birdsong, and to little children—and I am so grateful that you pointed me to hope.

We’re less than three weeks out from the release of Good Soil. Please preorder. Sign up to join me somewhere on tour. And if you’re part of a book club, a discussion guide has been posted; if your group decides to read Good Soil, please email me at makebelievefarmer@gmail.com and, if you like, I’ll try to join you one day via Zoom.

I am also accepting all prayers and good vibes. Thanks, as always, for being alongside me through all this. If there’s anything I can be praying for on your behalf, I’d count it as a privilege.

All my best,

Jeff

That was beautiful Jeff. I love tour thoughts on bitterness. That's such a deep topic. I'm going to try your recipe. I'll let you know how it goes.

Love the way you put your thoughts to words - beautiful reflection on bitterness. Will be turning it over in my mind for a while!

Also, preorder placed! Thank you for the reminder - I’m so very excited for your book