Let the Reader Understand

Some fragmented thoughts on a new lectionary centering women's stories, tomatoes, eggplant, and music for these troubled times

Hello, friendly reader.

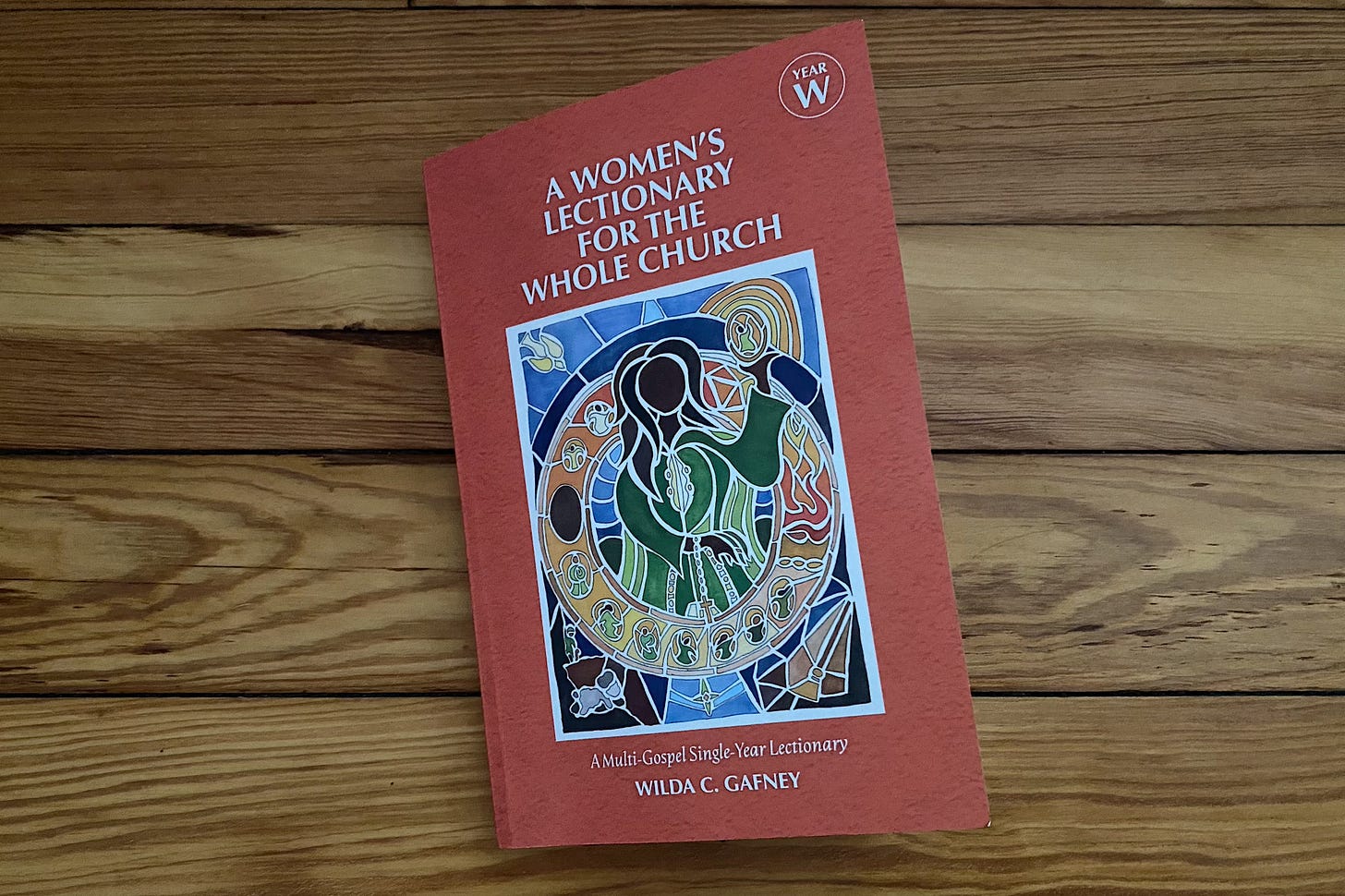

Last week, I spent some time on Zoom with the Rev. Dr. Wil Gafney. A professor of Hebrew Bible at Brite Divinity School, Dr. Gafney is the author of the new book A Women’s Lectionary for the Whole Church, which was published on Tuesday.

Gafney and I met in 2018, at the first Evolving Faith gathering. In her EF talk, she invited the audience to fill in the rest of this phrase: “God is the God of Abraham,...”

Instantly, the room responded: “…Isaac, and Jacob.”

“Who is missing? And why?” she asked. “And how does that affect the ways in which we read, hear, interpret, teach, and preach the text?” (You can listen to or read a complete transcript of her remarks here.)

Such probing questions, such teacherly curiosity, animated that talk and infuse the rest of her work, including A Women’s Lectionary, which centers the stories of women in Scripture. Lectionaries, which are common in both Judaism and Christianity, are liturgical schedules of scriptural readings, typically over either one or three years. Many Protestant churches in the U.S., Canada, and the U.K. follow the three-year Revised Common Lectionary, which has been in use since the early 1980s. (I have the “W” version of A Women’s Lectionary, which covers one year. Gafney is still completing the three-year version; Volume “A” of the three-year cycle was released simultaneously with the “W.”)

Lectionaries typically draw lines of connection among passages from different sections of Scripture. Gafney’s follows the traditional formulation—each week features readings from the Hebrew Scriptures, a passage from the psalms, and selections from the epistles and the gospels—and it begins with the first Sunday of Advent. Immediately, you realize that this isn’t your grandfather’s lectionary. This one begins with Hagar. The story of a messenger of God appearing to the enslaved woman of Abraham and Sarah’s household to announce that she will give birth to a son named Ishmael is paired with the story of a messenger of God appearing to Mary to announce that she will give birth to a son named Jesus.

“One huge aim of this project is biblical literacy,” Gafney explained. While nearly everyone knows that an angel appeared to Mary with a pre-birth announcement, “many people are not aware that this thing has antecedents. All these women have had encounters with divine beings,” she said. “So in a way, I didn’t choose to begin with Hagar; Hagar came first.”

Another aspect of biblical literacy is cultural competency. Gafney hints at this with her translation of Mary’s proclamation in Luke 1:38—specifically the Greek word δούλη (doulē). In the NIV, Mary says: “I am the Lord’s servant.” In the King James, she says, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord.” And the NRSV renders it: “Here I am, the servant of the Lord.” Gafney’s translation: “Here am I, the woman-slave of God.”

It’s bold, unexpected, and a striking parallel with the story of the enslaved Hagar. As Gafney explained it to me, servants in ancient times weren’t servants as we understand them today. “They had no control over their bodies or their reproduction. They were not entitled to their own children. Their bodies could be mutilated. That is not servitude,” she said. “Culturally, when people abase themselves, they are choosing the lowest rung of the societal structure: I am your slave. My body is in your hands.” Throughout the lectionary, she doesn’t shy from the word “slave” when appropriate: “It is important to me as a Black person who comes from a trajectory of enslavement to be honest about how normative the words ‘slave,’ ’slavery,’ and ‘enslavement’ are in the Scriptures—even on the lips of Jesus.”

One of my first impressions of Gafney upon meeting her and interacting with her was that she uses and chooses words with uncommon care and laser precision. In the green room at Evolving Faith 2018, she gently corrected someone who called her a theologian; “I am a Hebrew Bible scholar,” she said. And when she said that she was “bemused” by the gathering’s largely ex-evangelical audience, someone thought she meant “amused.” “I said ‘bemused,’ not ‘amused,’” she said, pointing to the difference between the commonly misunderstood words; the former suggests puzzlement, the latter entertainment.

I don’t want to be misunderstood either: Her precision shouldn’t be mistaken for stern dogmatism. In A Women’s Lectionary, her thoughtful language blossoms with artful ingenuity. The layered beauty of her diction halted me repeatedly, inviting me to reexamine a sentence’s filigree. For instance, she notes that Scripture contains so many women’s stories, yet “the extant lectionaries do not introduce us to even a tithe of them.” Even a tithe. Not “a few.” Not “many.” Even a tithe. This brief phrase evokes not just mere number but also loving duty and holy attention.

Words and stories, language and literature, have captivated Gafney from childhood. Her denominational journey has been multifaceted and diverse—Methodist on her father’s side, Baptist on her mother’s, Gafney was baptized in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, attended a “nondenominational happy-clappy white church” as well as Catholic school in her teens, went to a Quaker college, was ordained in the AME Zion church, and is now an Episcopal priest. But it was in Sunday school at an AME church that she began to fall in love with the Hebrew Bible. “Nobody grows up on the epistles,” she said. The Hebrew Bible’s stories “were the stories I liked.”

As a child, she also saw some written Hebrew and found the shapes of the words beautiful. “I said I wanted to look at this language with the pretty letters and see if I can learn it,” she recalled. She began teaching herself very basic Hebrew even before she went to seminary. Then, at Howard University Divinity School, she studied with the Old Testament scholar Gene Rice: “He made the text come alive in the way that all great teachers are said to do.”

When I went to seminary, I was told that you either love Hebrew or you love Greek—and that artists, creatives, and poets typically love Hebrew. So imagine my devastation when I did well in Greek but got destroyed by Hebrew; on one quiz, I scored a 35 out of a 100, and that’s after the professor spotted us 5 points. “I learned fairly early that I hate Greek, even though it is basically Latin,” said Gafney, who studied French and Latin in high school. “New Testament people are going to pass out, but Greek is Latin plus a bunch of horrible stuff thrown in, and I thought, I really loathe this language.”

Gafney’s care for the craft of writing hints at her love for reading. She devours everything from what she calls “trashy fiction, to rest my brain,” to the sci-fi novels of N.K. Jemisin. She read one chapter of Jemisin’s The City We Became—it’s enticingly entitled Boogie-Down Bronca and the Bathroom Stall of Doom—“three times in a row because of the joy the words gave me.” She has a special affection for skillful puns and clever turns of phrase, whether in popular fiction or academic prose. An example: the Judaic scholar Ilona Rashkow’s 2000 monograph Taboo or Not Taboo, which has a chapter on circumcision called “Cut or Be Cut Off.” “You think, What is this related to?” Gafney said. “Let me read!’”

There’s a profound hospitality about Gafney, whether you’re reading her work or engaging her in conversation. I love how she gently, thoughtfully questions the question. When I asked if there was a Bible story of a marginalized character that has especially shaped her and her faith, she asked, “Marginalized for whom?”

Huldah, a teacher in Jerusalem during King Josiah’s reign, has been a formative figure for Gafney. “But I wouldn’t consider Huldah marginalized. She’s a woman prophet. She serves the monarch. She is responsible for the canonization of the very first piece of Scripture. Those are not marginal things,” she said. “But her story is marginalized. Her story is not in the Revised Common Lectionary.”

As Gene Rice’s research assistant, Gafney researched Huldah for a commentary on the books of the Kings. “I said, This story is it!” As II Kings 22 tells it, King Josiah had a problem. The high priest Hilkiah had found a scroll containing the Book of the Law, which was then read to the king. Josiah realized that the people had been breaking the holy law, and he instructed his courtiers to find a prophet who could inquire of God how to make things right. That prophet was Huldah.

Gafney wrote a paper about Huldah, which eventually became the basis of her PhD dissertation, which eventually became the basis of her first monograph, Daughters of Miriam. During her PhD research, she realized how many books about King Josiah’s reforms lacked any substantive discussion of Huldah yet contained numerous chapters speculating as to why Jeremiah and Zephaniah, contemporaries of Huldah, weren’t asked for their wisdom on the matter. “Scholars would build these fantasies about the prophets who were not chosen for this job and ignore the prophet who was,” she said. “Huldah’s story and I have gone a long way.”

Searching, seeking, exploring, wondering which stories are told, delving into which ones are not: Both as a scholar and as a human, Gafney is profoundly openhearted. She’s frank about what she doesn’t know, what she hasn’t figured out, and how she’s still listening and learning. She acknowledges, for instance, that “by making this project explicitly feminine, it can become exclusionary and reinforce the gender binary.” She understands the desire of some readers to overhaul Scripture’s gendered language completely. “But I struggle with the space between needing to put the woman back on the page and moving to ‘siblings’ and ‘children,’” she said. “We are erased by androcentrism—and then we never appear.”

One key word in the title is “a”; this is a lectionary, not the lectionary. (NB: There is another new lectionary entitled The Women’s Lectionary. Caveat Googler.) Perhaps there’s an implicit invitation for others to create their own, lifting up other tones and timbres in the stories of God’s people to create a more holistic chorus. “This project can’t be everything for everyone,” she said. “As I listen to nonbinary kinfolk, I realize this is a growing edge for me, and we’ll see how that unravels.”

Part of the unspoken desire is to feel a closeness to Scripture as well as to God, a longing that can be especially acute for those who have been told that the divine is not for them. Gafney knows that Scripture can be difficult for many people, especially those whom it has been used against and especially those who associate the Bible with religious trauma. “The text is awful in places. So I don’t say to people: You’ve just had bad pastors and preachers. Some of the texts are horrible on their face. And it’s also used badly and used viciously. Those two things are real,” she said. “But I also say: There’s more to them. There are other ways to look at the texts.” Scripture can be as complicated, as fraught, as disappointing, as the humans who wrote these words down. “It’s okay if you can’t read it right now. It’s okay,” she said. “Don’t throw all of it out; put it in your back drawer. And then talk to me about where you experience God. Where do you see God? Where do you hear God?”

I had a couple of questions for Gafney about the set of readings for last Sunday.

The epistle reading was Hebrews 1:1-9, and I was struck by how God is named, in verse 3, in both Gafney’s translation and the NRSV, as “the Majesty on high.” In her notes, Gafney points out that this is a rare instance in the Greek of a feminine noun—Μεγαλωσύνης (Megalōsynēs)—being deployed to describe God. “That is where I began using ‘Majesty’ for God. I love that God is the Majesty on high and that it is a feminine noun,” she told me. She had not caught that detail before. But that’s the thing about Scripture: “Some of these texts, I’ve translated many times. I’ll pull up the translations and then do them over and I’ll say, I never saw that word before in my life. That’s part of what continues to engage me. The text is interactive; you experience the life in it as it interacts with you.”

Her psalm selection came from 47, a song of praise that exhorts the people to “clap your hands; shout joyfully to God with a joyful shout” and reminds them that “God is sovereign over the nations.” With all the world’s present troubles, I confessed that these words felt alien to me. Where is God amidst all this? What if we struggle to join a chorus of praise?

“I don’t know,” she said. She thought for a moment. “Maybe I would start in a place that all of us would recognize—the point of doubt.” The ninth verse of Gafney’s translation of Psalm 47 reads, “The nobles of the peoples gather as the people of the God of Hagar and Sarah. For to God belong the shields of the earth; she is highly exalted.” “We are not there yet,” Gafney said. We approach verse 9 as aspiration, not reality. “Maybe we are in the space between the verses.”

For a time, Gafney belonged to a Reconstructionist Jewish synagogue in Philadelphia, and as part of her PhD coursework, she received rabbinic training. That taught her to read beyond the words on the page. “Torah is not only words but also all the spaces between all the letters and all the words. The way rabbis tell stories and do interpretation, they’re doing all this stuff in the spaces where there isn’t text,” she said. “It’s a rabbinic practice to read the text between the text.”

If God feels distant, if God feels unapproachable, one experiment might be to try to find an alternative name to use. Sometimes you need a grand and majestic God; other times, what you long for is an intimate God who dwells in the details. An appendix to A Woman’s Lectionary contains all the names and titles Gafney uses for God in the volume, some familiar (Holy One, Loving God, Most High) and others less so (Dread God, Mother of the Mountains, Warrior Protectrix). Often, Gafney returns to one particular name of God: Emmanuel, which means “God with us.” “It means that the fullness of God’s love is with us in a variety of ways: In an explicitly Christian way, in the life and continuing ministry of Jesus and the Holy Spirit. And in the broader way, for people who are not sure about what I call ‘Christian fuzzy math’—three but one, one or three, or maybe it’s two, because one came to earth. For those who can’t navigate that, or God as sovereign and parent and nurturer—God is with us.”

She carefully nuances what “Emmanuel” means, because she doesn’t view God’s presence as panacea, neither in the texts nor in the world. “When the news in the text is bad, because a woman is being used as an incubator or someone is being brutalized, it’s not that God will fix it and make it all right; it is not always all right in the text,” she said. “Emmanuel—the name and the title and the story—is about God being with you when it’s not all right. That has become the heart of the Gospel for me.”

The day before we spoke, Gafney, a prolific tweeter (@wilgafney), had posted on everything from COVID to the TV show Torchwood to patriarchy to being “that terrible person [who] replied all to my entire faculty and staff no less than three times in the past week.” Haiti was weeping, Lebanon languishing, Afghanistan collapsing. “The God who loves so deeply as to subject themselves to the human experiment is with us in all of these things,” she said. “And sometimes that’s all I can hold onto in the horrors of the world.”

One of Gafney’s favorite names for God in the Hebrew Bible is “the Fire of Sinai.” “It’s beautiful and poetic and powerful,” she said. “It hearkens back to commitment and covenant. It speaks to me as a believer and as a preacher.”

After our call ended, I thought about that name for God, one I’ve never heard or used before. Yes, fire can destroy. But amidst the cold, fire also brings warmth. At night, it illuminates. It can cleanse. It can transform what’s inedible into something nurturing, something sustaining. Just when you think the flame has died out, it can roar back to life. It can serve as a symbol of resilience and a beacon of hope—and God knows we could all use some resilience and some hope right now.

What I’m Cooking: Our Brooklyn friends Dan and Ami came for Sunday lunch. They’ve been at our table many times before, so I feel freer when cooking for them.

We had our first real harvest of tomatoes from the garden—enough to make a salad with basil from the yard and some locally grown peaches from the farmers’ market. Slice the peaches, which should be ripe but not too ripe, into wedges and toss them in a bit of olive oil before grilling them in a grill pan until you get good char marks. Then toss the sliced tomatoes with the peaches, finely chopped basil, some flaky sea salt, a good dousing of balsamic vinegar, another of olive oil, and some freshly ground black pepper. To me, this tastes like summer in a bowl.

Something else I made for lunch: a Malaysian dish called terung soy limang—pan-fried eggplant in a glaze of soy and lime juice. I learned to make it when I traveled to Malacca in late 2019. It’s a great side dish in a meal with abundant spice and fat; the sour and savory glaze provides a bright counterpoint. Take an eggplant—I used Japanese, but non-Japanese is fine too—and chop it into small wedges maybe two or three inches long, an inch or so wide. In a bowl, salt the eggplant generously and let it sit for half an hour to extract moisture. Coat the eggplant pieces lightly in salt, pepper, and cornstarch. Then pan-fry them in hot oil over medium-high heat until they’re cooked through and lightly browned on all sides. In a separate bowl, mix the juice of one lime, two tablespoons of light soy sauce, one tablespoon of dark soy sauce—if you don’t have different soy sauces, just use three tablespoons of what you have—and a teaspoon of sugar. Pour this mixture over the pan-fried eggplant and reduce it for a minute or so until it’s no longer thin. Season to taste with a bit more salt and pepper, and garnish if you wish (on Sunday, I just forgot and it was all good) with some finely minced green onion and chili pepper.

What I’m Listening to: I’ve written before about Max Richter’s haunting “On the Nature of Daylight,” which he wrote as a meditation on the beginning of the war in Iraq in 2002. That piece appears on the new album Exiles, which features the conductor Kristjan Järvi and the Baltic Sea Philharmonic performing new orchestral settings of Richter’s stunning music. Richter wrote the title track in 2015, in response to the sinking of a migrant ship in the Mediterranean Sea, which killed more than 800 people, including many children. “Is there a better way for us to be headed?” Richter said in a recent interview with The Guardian. “Are we going to be able to shift things into something more humane, more sustainable, and a bit more equal?”

The theme “exiles” has been much on my mind this week.

We are exiled from our normal lives right now, as long as this pandemic continues. What even is “normal” anymore? Though I stopped dating these letters by how many days we were into Coronatide, perhaps that choice was premature and unwise. Please keep wearing your masks. Please get vaccinated if you can and if you haven’t already. Please keep thinking about how to love our neighbors well.

So many others are exiled from their normal lives right now too, for other reasons: Those who have survived political tumult and a devastating earthquake in Haiti. Those who have fled a collapsing Afghanistan as well as those who cannot or will not. Those who live amidst the systemic economic and political failure of Lebanon, which once again finds itself ailing. Those whose lives have been scorched by fire or overwhelmed by flood. Those in so many other lands and so many other places where there isn’t peace, where there isn’t stability, where there isn’t any certainty about what tomorrow will bring. Please give to a credible charity if you are able. Please hold these peoples in your prayers. Please keep thinking about how to love our neighbors well.

Many of us are exiled from religious traditions that once felt like home, at least for the most part, at least until we were honest about our questions and doubts—and maybe even about who we are. On Sunday, I will be preaching at CrossPointe Church, where I am partway through my year as teacher in residence. This week’s sermon is part of a CrossPointe series entitled “Weapons and Balm." The series explores how Scripture can be used as a profane weapon as well as experienced as a holy balm. We’re in the balm portion of the storytelling, and my sermon explores how the Bible can be read as a book of belonging and of collective hope. The core text: Psalm 22, from which Jesus quoted on the cross (“my God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”). You’ll be able to find the video on CrossPointe’s YouTube channel from 10 a.m. ET on Sunday. Please keep thinking about how to love our neighbors well.

Thanks for reading. This was a long one! But I thought Dr. Gafney’s words and work were worth it. As always, I’d be grateful to know what’s stirring in you, what’s on your heart and mind, and how I might be able to remember you and yours in prayer.

I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Much love,

Jeff

I was only part way through the read when I started taking screen shots and highlighting- first one being about not throwing the whole Scripture out when it feels weaponized or complicated, but putting it in a back drawer for later -and remember other ways to look for God. You brought out Dr. Gafney’s words so beautifully in your article. Grateful for your shared conversation and insight.

As always, Jeff you have opened another window for me…I can’t wait to read Dr. Gafney’swork. Thank you.