Now That the Leaves Have Fallen

Some fragmented thoughts on the maple tree out front, liberation, butternut-squash soup, and a song about how it will all end

The 163rd Day after Coronatide*

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Greetings, dear reader.

For weeks, the leaves on the maple tree outside my study window have been turning—green to gold and orange and red and brown. Just now, I realized that the branches I can see bear only a few withered remnants. All else has fallen.

The leaves did their duty, nourishing the tree throughout spring and summer, and with the arrival of autumn’s cool, it was time for them to go. The tree has turned its attention to storing up resources for the coming winter, banking sustenance in its roots.

Sometimes I wonder whether the maple outside my house is lonely. Scientists have learned so much in recent years about the ways in which trees listen to one another and support one another through fungus-enabled subterranean networks. In a healthy forest, “trees share water and nutrients through the networks, and also use them to communicate,” according to this Smithsonian interview with the German researcher Peter Wohlleben, author of The Hidden Life of Trees. “They send distress signals about drought and disease, for example, or insect attacks, and other trees alter their behavior when they receive these messages.”

From the way we use them for ornamentation and raw materials, you wouldn’t know that trees have lives of their own or that they’re made for community. Does our maple complain to the other trees on our street when Fozzie insists on peeing at its base? There is no forest here to speak of; have the pavement and the sidewalks inhibited its relationships with others of its kind? What is it like for this maple essentially to go it alone? I think it’s a Norway maple; can it chat with the Japanese maple down the block? Is it simpatico with the oak trees around the corner?

Anyway, it feels as if the fallen maple leaves took all my energy with them.

I don’t think we’ve even begun to recognize the psychological, emotional, and spiritual toll that 2020 has had on so many of us. How can we calculate what we’ve lost in terms of time with loved ones? How can we measure the cost of longing and the price of uncertainty? How can we gauge the compound effect of this year’s griefs, which have layered like sediment atop the sorrows of 2019 and 2018 and 2017?

Sometimes you only realize how heavy something is when it’s finally gone. Tristan and I were walking Fozzie the other day, and I said that learning the election results had lifted a physical weight from my body that I didn’t even know was there. I think a huge part of that physical weight had to do with a profound and growing sense over the past four years that I and so many others neither belonged nor were wanted in the U.S.—and that our presence wasn’t just an irritant; it also precluded the country’s return to “greatness,” flawed as that concept might be.

Perhaps some of us have come to see a sense of belonging as a thing that an individual could own rather than something that has to be shared. Like the trees, we were made not for independence but for interdependence. The American fixation on “freedom from”—freedom from others telling us what to do, freedom from mutual responsibility, freedom from government tyranny—has devastated us. It represents scarcity and fear. It sees threat around every corner. It worries constantly about protecting all that could be lost.

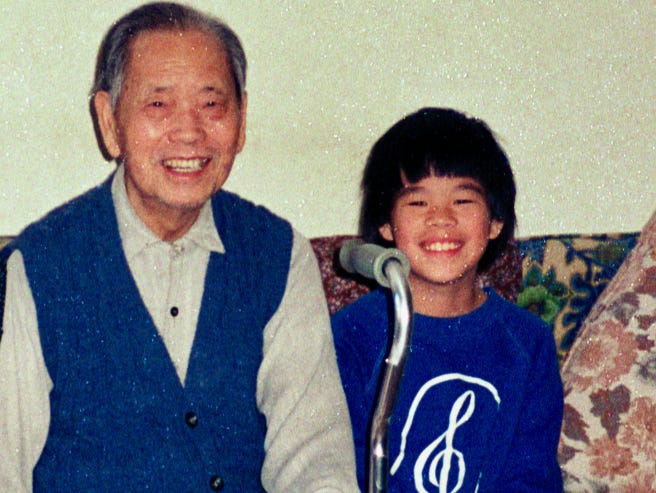

It’s not that I don’t understand the power of liberty; after all, my grandfather’s pastoral ministry in China ended because of a Communist government that was—and is—oppressive, anti-religious, and opposed to individual liberty. But I struggle to believe that liberation is complete if you can understand only what you’ve been liberated from without any conception of what you’ve been liberated for.

“Freedom for” opens us up to possibility. It pushes us past our narrow self-interest. And it points us toward the kind of interdependence—freedom for the common good, freedom for mutuality, freedom for the sake of love—that will make us better and stronger. Of course it feels risky, because it requires trust, and it also demands imagination about what could be.

If 2020 has taught me anything, it’s that I can’t go it alone—and I don’t want to. I’m more grounded when surrounded by others who remind me who I am and who I might someday become. I’m more rooted when I recognize the others on whose strength I depend. And I’m more resilient when I remember that I belong to you, you belong to me, and we belong to each other—and that’s the way it was always meant to be.

What I’m Growing: While a couple of my bok-choy plants in the backyard have flowered and gone to seed, several others keep offering new leaves. I must have cooked at least half a dozen meals from just this little cluster of plants alone.

I’m starting to imagine what I might do in the garden next year. I think I qualify for a 25x50 plot next year—they only let newbies have half-plots—which is much more space and will require much more discipline. I know I need to reimagine my grow-light setup, because I don’t think the tomatoes and peppers had enough heat. I’d like to plant a lot more beans, and while the zinnia did great, I have fantasies of different kinds of flowers. What else should I plant? Any suggestions?

What I’m Cooking: We ended up with two butternut squash from the volunteer vines in our backyard. On Tuesday, I cut them open, spooned out the seeds, slathered the halves with butter, and roasted them for 45 minutes. Then the peeled, roasted squash went into a pot with some broth, a little milk, nutmeg, red-pepper flake, salt, and black pepper. Simmer it for a bit, whiz it around with an immersion blender, and you have soup! Meanwhile, since the oven was still hot, I made a batch of biscuits and put a couple of slices of bacon on a baking sheet and popped them in until they were crisp. (I always make bacon in the oven now. Turns out great, and much less messy than on the stovetop.) The crumbled-up crispy bacon makes the soup—we are who we are—and the whole thing feels like a warm embrace on a chilly autumn evening.

What I’m Reading: I pulled my copy of Pádraig Ó Tuama’s In the Shelter, which was a gift from my friend Nate, off my shelf the other day. It was there, I was there, and it just felt right. I flipped around for a bit, and then I landed on this paragraph: “We are the stories we tell about ourselves and we are more than the stories we tell about ourselves. We fiction and fable our lives in order to tell of things that are more than true and we lie—if only by omission—by reducing ourselves to mere facts. Ní fiú scéal gan údar we say in Irish— ‘there’s no worth to a story without the teller.’ We create anxiety for ourselves by either rejecting or being limited only to the story of our lives. To live well is to see wisely and to see wisely is to tell stories and to tell stories is to tell of things that are always changing, because even if the stories don’t change, the teller does, and so the story always moves.”

What I’m Listening to: Early in my reporting career, I packed my rattiest gear, put on my grungiest clothes, and snuck into Zimbabwe as a backpacker. The Zimbabwean government was then severely restricting press freedoms. My assignment: to interview musicians who used their art to protest the ruling dictatorship. I spent a few days traveling with Oliver Mtukudzi, known to his fans as Tuku. Tuku, who died early in 2019, forged a unique style that blended different traditions; listen closely to his songs and you might hear mbira (thumb piano) and hosho (drums indigenous to his Korekore people) as well as gospel. “Magumo” (“the end,” in Shona) came to mind the other day. I don’t know why. “You beat your chest/ Feeling all your importance/ How will it all end?” it goes. “You look down upon others, despising/ As if they aren’t human beings/ How will it all end?/ You don’t respect God/ What will be the end? How will it all end?/ You may have power, much power/ Yet you oppress the weak/ How will it all end?”

I don’t know if I’ve made any sense at all this week. As I said, I’m tired! But as we move toward Thanksgiving, which is perhaps my favorite holiday of the year, I’m trying to lean more into the discipline of gratitude. Why is it so hard? I don’t know. It doesn’t make any sense. Whenever I practice it well, I always emerge encouraged and refreshed, energized and renewed. As with so much else, I guess, we don’t always recognize what’s good for us.

Thanks for reading. I’m so glad, as ever, that we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Yours,

Jeff

* I’m still counting my days from June 1, when my governor, Gretchen Whitmer, ended Michigan’s stay-at-home order. Our COVID-19 numbers have once again reached a level technically classified as “horrifying.” Please, for the love of God and the sake of your neighbor, continue to wear your mask, stay physically distant, and remain safe.