O Love That Will Not Let Me Go

Some fragmented thoughts on Advent-appropriate love, the Apostle Paul's heartfelt longings, the coming of a baby, and Christmas

Advent IV

Friday, December 23

Austin, Texas

We’re still in Advent, not quite to Christmas, friendly reader, so please allow me one more grumpy moment.

Last week, I was doing some uncharacteristically early prep for a sermon next year, and I saw that one of the assigned Scripture passages for the service is I Corinthians 13. It’s that familiar part that talks about what love does and doesn’t do. You might know it because you’ve heard it at so many weddings; I immediately felt annoyed because I’ve heard it at too many weddings and I’ve never really wanted to preach it: “Love is patient, love is kind...”

I Corinthians 13 is not really about couple-y love or familial love. Its love—agape—doesn’t depend on familiarity or reciprocity. Utterly unselfish and unconditional, it isn’t by definition a mutual love. Empathetic and altruistic, rugged and robust, this kind of love pushes against the gauzy sentimentality that typifies, say, a modern wedding or a Hallmark Christmas movie. In other words, the love that Paul writes about in his letter to the Corinthians seems just right for these waning days of Advent, because it testifies to how we ought to wait, and it hints at what we’ve been waiting for.

Love is patient; love is kind; love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable; it keeps no record of wrongs; it does not rejoice in wrongdoing but rejoices in the truth. It bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. Love never ends.

I’m on board with patient and kind love—especially if it’s offered to me. And given how often I make mistakes, I’m drawn to the idea of a love that keeps no record of my wrongs. Honestly, I struggle a bit more, though, when it comes to extending such patience and kindness to others, particularly those who have hurt me. And when it comes to those wounds, surely good and just accounting practices would allow at least some basic record-keeping.

In other words, the kind of love that Paul writes about is the kind I’d like to receive. But I’m not sure it’s the love I know how to give.

Paul is characteristically opaque when he writes of a “love that does not insist on its own way.” Could the man not have offered some helpful examples? Did anyone suggest to him that he ought to show, not tell?

Then, when Paul says that love “bears all things”... well, this is perhaps the most challenging, countercultural aspect of his elucidation of love. Other translators say that such love “covers” or, worse yet, “suffers.” So often we think of love as affirmation and validation rather than perseverance and suffering. When Paul writes in this vein, surely “all things” can’t possibly mean the horrible things that have been done to me or the hurtful words that have been spoken or the harms that have been inflicted. Where is the safety and security in such love?

For now we see only a reflection, as in a mirror, but then we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known. And now faith, hope, and love remain, these three, and the greatest of these is love.

I really wish I could hear the tone in Paul’s voice. Though Paul is often flattened and caricatured, especially by his modern readers who find him retrograde and irritating, his writing is full of his complicated humanity—flashes of humor, bursts of beauty, profound desire for belonging, gratuitous anti-vegetarian prejudice.

The love that Paul preaches doesn’t promise instant gratification or creature comforts. It is not a fluffy spiritual duvet under which one can crawl at any given moment; if anything, it leaves you vulnerable and exposed. Which makes me wonder: Was he writing to himself as much as he was to the Corinthian church? Was he reminding himself of what he was trying to believe, so as to gird himself for the onward journey? Was he attempting to pen his faith, his hope, and his love into being?

I get that.

Regardless, it moves me to read Paul’s trust that his future and complete self-knowledge will come in the midst of a collective act of seeing and being seen. The fullness of his “I” will arrive with the wholeness of the “we.” For now, though, we do our best to hold onto things unseen, to believe in unfulfilled promises and sketchy possibilities.

Love is patient.

I’ve been reading and re-reading Paul’s words in the light of this holy week—and it hits differently, perhaps more tenderly.

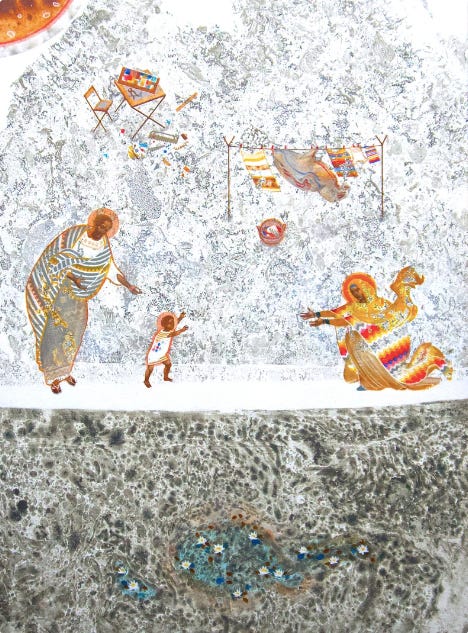

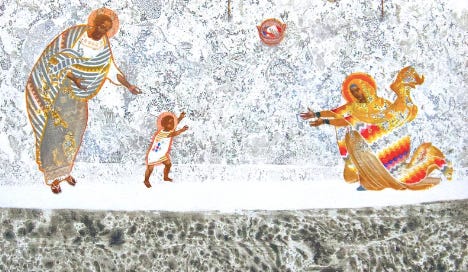

We celebrate Jesus’s birth with the benefit of so much hindsight—2,000 years of sanitized storytelling, which is to say story-retelling. Of course love can be patient and love can be kind when it comes to our sweet and stirring Christmas-pageant version of the Baby Jesus story. But what about the messy, painful actuality of the event? I’m sure Mary would have some things to say about what she felt.

I have to wonder, too, how we might have responded if, say, we were living in Bethlehem, Jesus was feeling colicky, and Joseph was shouting, “I’m so sorry,” across the courtyard for the fifteenth time that night.

Anyway, even if a birth—even if this birth—is infused with particular meaning and significance, it was still just the beginning, still not the complete fulfillment of all the promises and possibilities. The kid had to grow up.

Love is kind.

Yes, there might be moments of beauty and transcendence, but mostly, a baby doesn’t offer the kind of ready affection that most of us would find affirming. A child can seem to take so much more than he gives. Especially in those worst moments—amidst an implacable tantrum, amidst the ear-lacerating shrieks—you have to believe in his possibilities. Somehow you want the best for the kid in the meantime.

Love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude.

Love so often shows up in unexpected forms. Like a baby, it can be exhausting. It can test your known limits—challenging you, whether you’re giving or receiving. Often its beauty is most apparent in retrospect. Sometimes its presence is clearest later, amidst its absence.

Love does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable; it keeps no record of wrongs.

We know the foolishness of insisting that a newborn child do better or differently. Nor do we hold an infant’s cries against it. We rejoice in new life and its possibilities. At our best, we summon something resembling love—or at least endurance. There’s a lesson, I suppose, in the baby’s infantile embodiment: We marvel at what is, yes, but we also have to hope in what will be.

And now faith, hope, and love remain, these three, and the greatest of these is love.

Maybe this is the Christmas spirit I want and need.

Maybe what I want more than anything is that dogged insistence that this story be true, and maybe you want this too: a soul-deep trust that promises will still be fulfilled, that possibilities will be more fully realized tomorrow than today, that this rugged and robust love is here for me and for us but also that such love is here for me and for us to live out too.

Maybe what I need, as Advent yields to Christmas, is a heart that yields ever more to such love—and maybe you need this too.

As Christmas comes, I wish you and yours a growing understanding of love’s promises and its possibilities. Where I live, the longest night has passed, and as the sun gradually lingers with us longer, I hope that you’ll once again be reminded that this love has come, and this love will come again.

While we spend a few days in Texas with friends and family, our dear Fozzie is in Michigan. The lovely family with whom he is staying sent this photo of the Fozz with one of his new friends

Wherever you are, may there be fires nearby to warm you, soft surfaces on which to land, and companions to remind you that you’re never alone.

I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Much love,

Jeff

Your words are a gift to all of us. Thank you.

1 Cor. 13 - to me - is a vision.