Olympic Spirit

Some fragmented thoughts on a family trip to the 2024 Summer Games, love, the messiness of church, potatoes, and a cover for my new book

Friday, August 9

Grand Rapids, Mich.

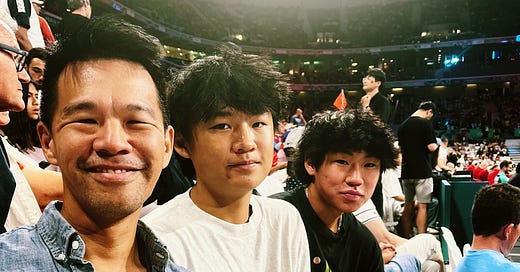

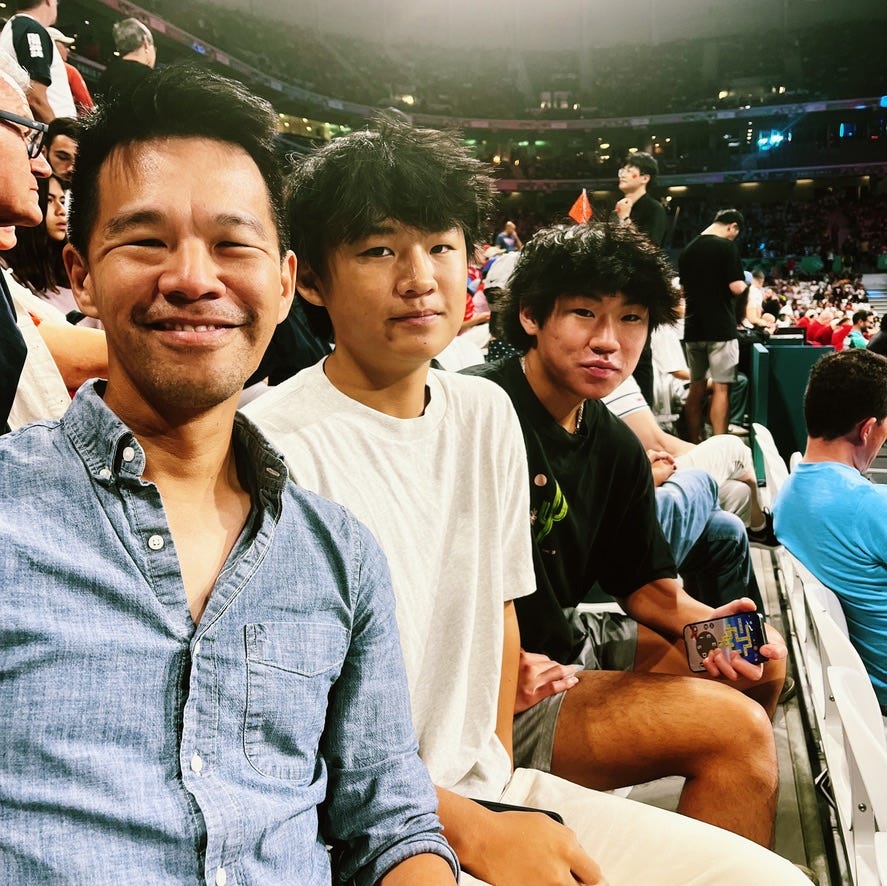

I got home last weekend from France, where I’d taken my nephews for the Summer Olympics.

This trip was a promise fulfilled: Years ago, I told my nephews that we’d go wherever they wanted when they turned 13, and this was sports-loving Ryan’s big adventure. The original plan had been to attend the Tokyo Olympics, but the pandemic ruined that. So Paris 2024 it would be, a month before he starts college—and because Ryan is a gracious sibling, he agreed to let his younger brother tag along.

I was naive about the challenges of traveling with teens. For instance, the dumbest possible question, which I repeatedly asked, was, “What do you want to do?” Every time, I forgot that the answer would inevitably be a shrug and a terse “I don’t know” or “I don’t care.” And while I did venture some culinary education—the boys gamely tried escargot and mussels—Ryan successfully turned the trip into one extended pasta bolognese tasting session; he happily ate, by my count, seven different versions of the dish. You love what you love, I guess.

This trip was no chore, though: I love my nephews, and I love the Olympics. As a kid who didn’t particularly care about sports, I turned into the biggest fanboy come Olympics time. I covered the 2004 Games, in Athens, for Time. In 2012, I happened to be in London for work and snagged some last-minute volleyball tickets. Every single time, I revel in underdog stories and root for the minnows. Suddenly weightlifting, taekwondo, and even climbing are strangely, if momentarily, compelling. The sight of medalists embracing their loved ones makes me cry.

Tales of good sportsmanship and all different kinds of heroism abound.

Did you hear the story about the Angolan handball captain who collapsed with a knee injury mid-match against Brazil? One of the Brazilian players came over, lifted her rival into her arms, and carried her gently to the bench. “There was no way I wouldn’t help her,” Tamires Araujo Frossard said afterward.

Separated by politics but brought together by sport, the North Korean and South Korean table-tennis teams took a selfie on the podium.

Hurray for the countries that won their first-ever medals, including Dominica (gold in the women’s long jump), St. Lucia (gold on the track, in the women’s 100 m, silver in the 200 m), and Cabo Verde (bronze in men’s boxing).

For the first time, my beloved Hong Kong won two gold medals at one Games, both in fencing.

I loathe boxing, the only Olympic sport that I refuse to watch. But my heart swelled when boxer Cindy Ngamba won a bronze—the first-ever such achievement for the Refugee Olympic Team, which includes athletes who have fled their homelands. (Ngamba, a lesbian, is from Cameroon, where homosexuality is illegal; she lives in Britain but doesn’t have a British passport.)

Over ten days, my nephews and I took in all different sports: Volleyball was wild, table tennis awe-inspiring. Football—soccer, if you must—was fun; who knew we’d get so invested in a match between Uzbekistan and the Dominican Republic? Rugby sevens was a revelation—lightning-quick, action-packed, wildly physical. (Also, the best bargain, with twelve matches in one session.)

Some sports are better on TV than in-person, but the cameras can never fully capture the crowd’s spirit. Of course the French fans were loudest; the incessant cries of “Allez les Bleus!” are still echoing in my ears. But in every venue, no matter what flags the spectators were carrying, the spectators applauded heartily for every valiant performance and cheered a little louder for athletes with no chance of medaling.

By the time we got to our last event, women’s basketball, we were honestly dragging a little. We also weren’t thrilled about the matchup: Spain vs. Puerto Rico. Olympics tickets go on sale more than a year before the Games, long before you know who’s playing whom in what session. And for the first half of the game, I wondered whether I’d chosen poorly. It was lopsided to the point of near-embarrassment; at the half, Spain led Puerto Rico 39-25.

What happened in Puerto Rico’s locker room during halftime? The team that arrived on-court for the second half wasn’t the team that had played the first. Feisty and scrappy, they threw themselves into the game with such aggression that I said, “This is more like rugby than basketball.” Puerto Rico went on a 19-to-5 run in the third quarter, and just into the fourth, they took the lead for the first time.

This was the sort of underdog comeback I love—until it wasn’t. Spain, fourth in the world, bigger and more imposing than Puerto Rico, managed a 63-62 win. Sometimes there’s no fairytale ending. Sometimes you pour yourself out and you can’t quite finish the way you’d imagined. Sometimes you fall short of the top of the podium.

But as the crowd gave Puerto Rico’s players a raucous standing ovation, I remembered that I believe that “winning” can come in many different forms: displaying immense heart, showing up with your best, putting in a courageous effort, showing up with your best.

For all that we saw, perhaps the most moving moment of these Games for me might still be something I watched on TV: Celine Dion’s rendition of “Hymne à l'amour” (Hymn to Love) during the opening ceremony, on a stage set on a glimmering Eiffel Tower. It was Dion’s first live performance in four years—and her first since she announced that she had a rare disease that causes uncontrollable muscle spasms.

The great French singer Edith Piaf, inspired by the love of her life, champion boxer Marcel Cerdan, wrote “Hymne à l'amour” in the spring of 1949. “If one day life tears you away from me, if you die and are far from me,” the song goes, “it does not matter, if you love me.” Those words proved strange foreshadowing: Six months later, Cerdan died in a plane crash.

It might seem an odd song choice for an Olympics opening ceremony, except that this was Paris, and love, broadly and even controversially defined, was a theme of the show. “Dans le ciel, plus de problèmes... Dieu réunit ceux qui s'aiment,” the song goes. “In heaven, no more problems... God reunites those who love each other.” May that be true—and maybe, at the Olympics, even in a world full of trouble and woe, we get just a tiny glimpse of that goodness.

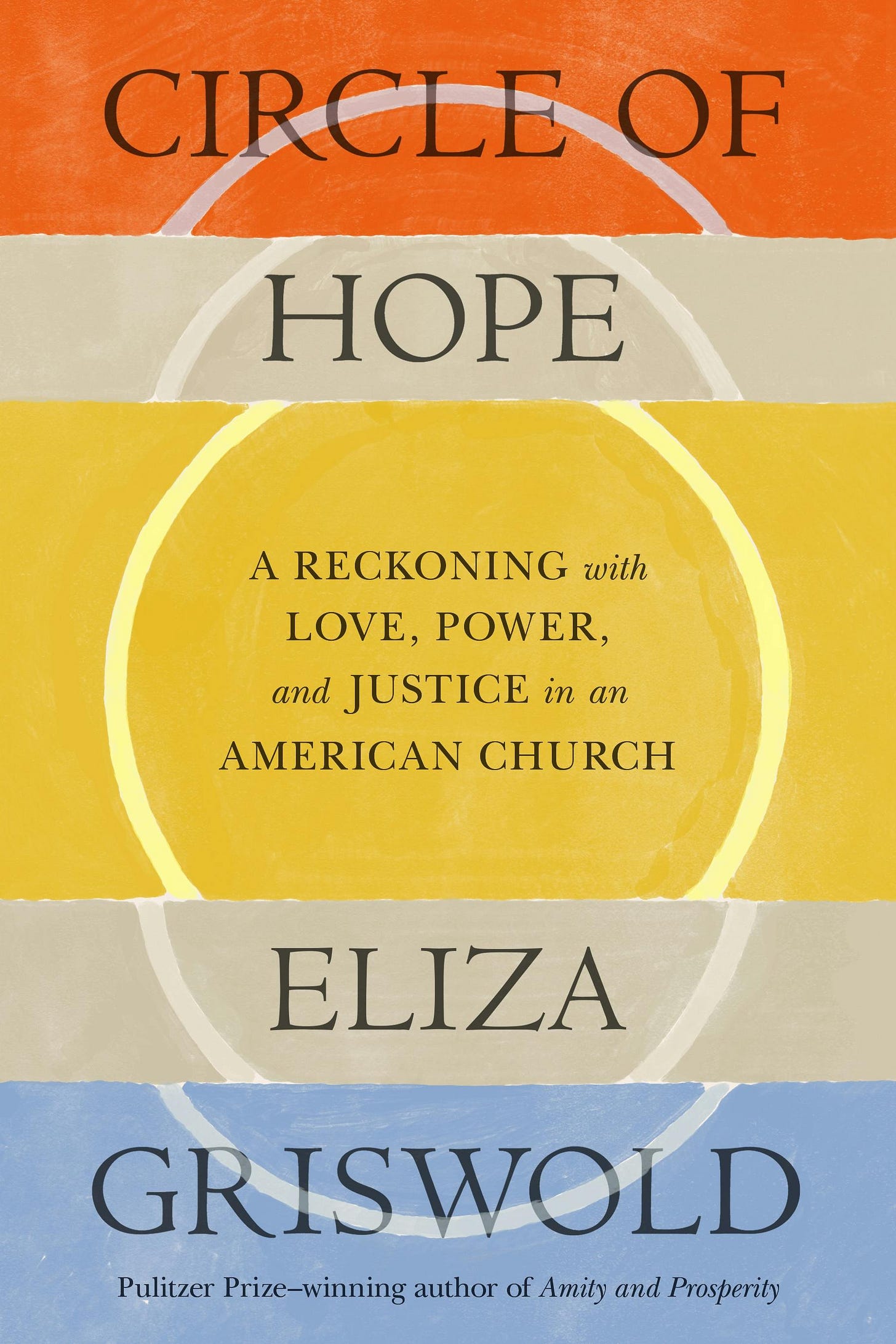

What I’m Reading: “Churches are messy places where people seek many things, among them a common understanding of something larger than they are, of God,” the journalist Eliza Griswold writes in her new book, Circle of Hope: A Reckoning with Love, Power, and Justice in an American Church. “This can be a beautiful, courageous endeavor that, in its effort to do right, usually goes wrong.”

Isn’t this the human story? Good intentions never guarantee perfect results. Beauty and courage almost always exist alongside ugliness and cowardice. Hope always carries the possibility of disappointment, even devastation.

Yet still we try—to do right, to live in community, to seek the good that is beyond the reach of any one individual. Griswold’s remarkable book, published this week, is an intricately reported, profoundly empathetic account of the valiant efforts of a Philadelphia church, also called Circle of Hope. What happens when a diverse group of people attempt to embody faithful justice but can’t quite agree on how? How do we translate the lessons of Scripture from the ancient page into contemporary community? What does it actually mean to live out love?

Messy.

I’ve known Eliza Griswold for a decade. She’s a wildly gifted reporter who specializes in immersion journalism, which requires investment that can’t be measured in mere hours or days. For her 2011 book The Tenth Parallel, she spent seven years traveling the borderlands of Christianity and Islam around the globe. For Amity and Prosperity, which won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction, she devoted another seven years to chronicling fracking’s effects on one Pennsylvania family.

For Circle of Hope, Griswold spent several years observing the Circle of Hope community, particularly its pastors. She is a pastor’s daughter herself; her father, Frank Griswold, served as the Episcopal Church’s presiding bishop. “I’ve spent much of my life at the edge of belief, observing how people organize their lives around what they hold sacred,” she writes. “I was raised to analyze human concepts of the divine.”

The pursuit of the divine that Griswold first saw at Circle of Hope, three years into the Trump administration, intrigued her. It was evangelical yet not right-wing, attuned to society’s needs, and full of possibility. “This bright and funny band of Jesus followers,” she writes, “promised not only to reclaim the moral heart of evangelicalism but also to serve as Christianity’s last, best shot at remaining relevant.”

Full disclosure: I’m no a dispassionate observer when it comes to this book. Two of my dear seminary friends belonged to Circle of Hope; I watched them pour so much love into their faltering congregation. Then, partway through the publishing process, Griswold asked me to help convene a group of pastors and scholars to provide feedback on her draft. Finally, I have an irrational love for the Church and a stubborn conviction that, with God’s help, it can be a force for mercy and justice in this world.

No spoilers here, except to say that the story of Circle of Hope is a humblingly human one—and, as with many of the best works of reporting, the story didn’t turn out how Griswold first imagined. “It’s uncomfortable to accept our flaws, let alone having them pointed out to us, hearing how we hurt one another and ourselves by clinging to received ideas,” she writes. “In some ways, this is the work of the exegete: to examine a story or an experience for what it reveals not only about the world, or God, but also about ourselves and what, in our embodied consciousness, must grow, or die.”

What I’m Growing: Potatoes. So many potatoes. Turns out I planted a lot of potatoes.

Even last season, when our crop was beset by potato beetles, we had enough to sustain us through Easter. I had no problems with potato beetles this season. I think I’ve only harvested about a quarter of the crop in our community-garden plot so far, and none of the ones growing in our backyard. So the coming months are going to be an extended potato festival in our house, so I’m in the market for new ideas: What are your favorite ways to cook potatoes?

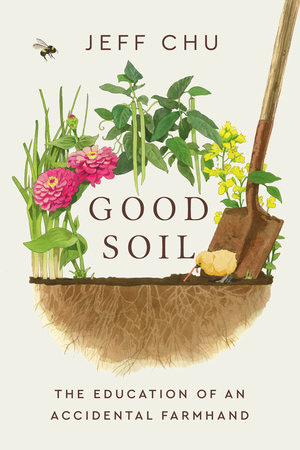

It’s been a little while since I gave you an update about Good Soil. We have a tentative publication date of March 25, 2025—mid-Lent, which feels right to me. Also, here’s the just-finished cover, featuring a beautiful painting commissioned from Joe McKendry, an artist who teaches at the Rhode Island School of Design. Ugh, I’m so nervous about putting this out into the world, but at least it looks pretty.

Grateful for your companionship. Thankful that you spend time with my words. What’s on your minds? How’s your garden? Anything I can be praying for?

All my best,

Jeff

One of my favourite ways to eat potatoes: boiled with the skin on, then cut in half and/or into quarters and fried in a cast iron frying pan with butter and avocado oil and seasoned with salt, pepper, paprika, garlic powder. I also love adding lots of onion slices and frying them with the potatoes. Sprinkle with fresh parsley or dried herbs. Serve with homemade mayo.

Only zinnias in pots for me successfully this year. But I found a volunteer basil plant near the alley that’s fairing far better than the potted one if my porch! Unexpected blessings.