Paying Attention to the Beauty of the World

Some fragmented thoughts on James Rebanks's new book "The Place of Tides," a decade of legalized same-sex marriage, and the "Good Soil" tour

Thursday, June 26

Grand Rapids, Mich.

Sometimes you have to subject yourself to another way of being to see yourself more clearly. Sometimes you have to travel far from home, away from everything you know—or think you know—to better understand your place and purpose.

British farmer and writer James Rebanks’s previous books, The Shepherd’s Life and English Pastoral (published in the U.S. as Pastoral Song), chronicle the agrarian ways of his native Cumbria and urge us to live in harmony with the land. In his latest, The Place of Tides, published in the U.S. this week, Rebanks goes further afield. He travels to a tiny Norwegian island to shadow a woman named Anna, who, in keeping with ancient tradition, guards wild eider ducks and gathers their down.

On its lovely surface, The Place of Tides seems to be a travelogue about a place largely left behind by modernity. But at its compelling heart, it’s a deeply moving interrogation of what matters and how we make meaning. “We endlessly shape and reshape our own stories to make ourselves feel relevant or seen—desperate to be the major character. But we don’t end up feeling seen, we end up drowning in noise, because everyone else is desperate to be heard as we are,” Rebanks writes. “The world has become a mad shouting match, making us distracted and anxious. I’d done all these things as foolishly as anyone else, and it was exhausting.”

He finds renewal in the company of Anna, who has chosen a countercultural way of being in the world. “It wasn’t that she had no ego, but that she mostly forgot about it, or shelved it,” Rebanks observes. Instead, she submits herself to a steady labor of care and attentiveness. Each spring, like a migratory bird, she moves out to sea. On a rocky outcropping, she continues an age-old practice of helping the nesting ducks and then harvesting the feathers they leave behind. “And in this radically pared-back life, she had found peace and meaning,” he writes. “She was the waves, the light, and the terns rising and falling on the bay. She was them, and they were her.”

Throughout The Place of Tides, Rebanks nudges us to recognize that there might be something at least partly deceptive about the stories we tell ourselves, not just about our own lives but also about the world. As in his earlier work, he questions the choices many of us have made, often without much thought: What makes for progress? What’s the price of convenience? For all we think we’ve gained, what have we lost? As he explores Anna’s corner of the world, a place “perfect for creatures like otters,” he finds himself at the mercy of “the coming and going of the tides.” At high tide, he’s restricted to no more than a few acres of walkable land, “much of it fissured and cracked slabs of rock. I was learning that our dreams of islands as places of freedom and escape are fanciful—an island is defined by constraints and limits.”

Yet constraints and limits can be grace and gift, focusing one’s vision and removing distraction. Rebanks is one of the preeminent nature writers of our time. He creates gorgeous, evocative word pictures, showing us how “the giant orange sun blazed low on the horizon as if someone had opened a furnace door” and introducing us to “a sad, wind-twisted bird cherry tree, no taller than an old man, its branches reaching out like a clawed hand.” Shaping dried seaweed into wreath-like nests for the ducks, “I sometimes thought of the crown of thorns that Jesus wore on the cross,” he writes. “Someone must have bound that crown round and into itself, like we were doing now—although the seaweed was only prickly, not thorned.”

The Place of Tides is a duet, really—an elegant dance between two remarkably observant humans. Rebanks describes Anna’s life as being “devoted to paying attention to—or, more than that, being completely committed to—the beauty of the world before her.... To see, hear, smell, touch, and taste the world.” He does much the same thing. He models how one can encounter someone and someplace so seemingly foreign, so apparently alien, and, in honoring it with curiosity and care, find understanding and nourishment, wisdom and even belonging.

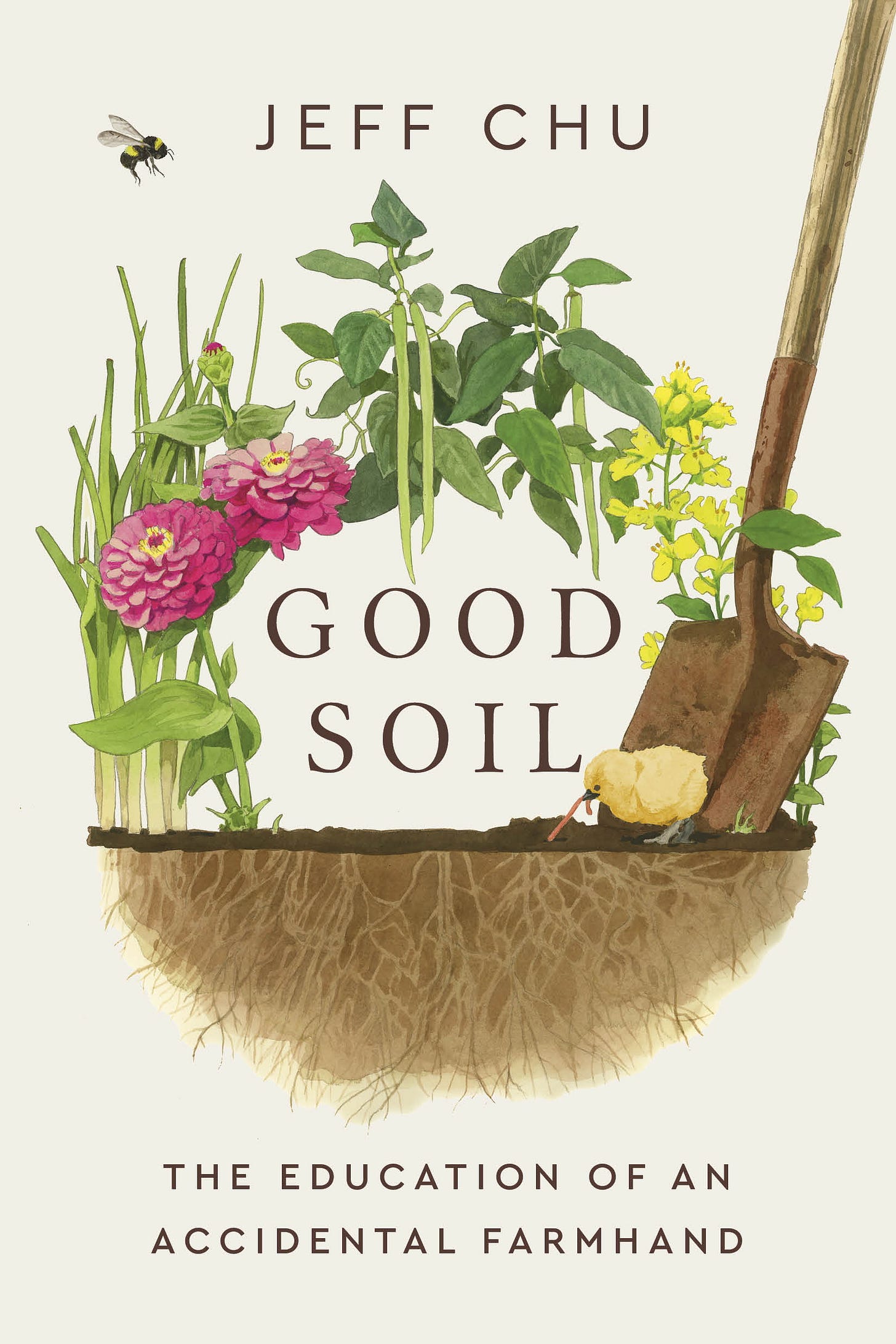

Full disclosure: I’m a biased reader. Some years ago, I was fortunate enough to be a student in a writing workshop held on the land stewarded by James and his wife, Helen, herself a gifted author (her book is called The Farmer’s Wife). There, I experienced the same warmth and hospitality that radiates from their writing. I wasn’t a particularly good student; my mind wandered, I didn’t follow the instructors’ instructions, and I held myself a bit aloof. Yet James met me where I was. On the workshop’s last day, he looked me in the eye and spoke a couple pointed sentences of encouragement that I held in my heart throughout the writing of Good Soil.

In The Place of Tides, James meets willing readers where they are too, offering hard-won hope that’s both timely and necessary. “We all have to go to work in our own communities in our own landscapes,” he writes. “We have to show up day in, day out, for years and years, doing the work. There will be no brass band, no parade. And we have to accept and keep the faith in each other, and somehow work tgoether. It is the only way we can make our own tiny deeds add up to become the change we all need.”

“The Place of Tides” is available wherever fine books are sold. Bookshop.org is always good.

What I’m Pondering: Speaking of change, today marks one decade since the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, the ruling that legalized same-sex marriage across the country. Tristan and I wed three years before, in 2012 in Massachusetts, which established marriage equality in 2005. Obergefell meant that our marriage was legally recognized in every other state.

“The nature of injustice is that we may not always see it in our own times,” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in his majority opinion. “The generations that wrote and ratified the Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment did not presume to know the extent of freedom in all of its dimensions, and so they entrusted to future generations a charter protecting the right of all persons to enjoy liberty as we learn its meaning.” As we learn its meaning: This phrase has stuck with me and has come to have even more significance in these topsy-turvy times, when it seems as if some might interpret liberty as something to be hoarded, even gatekept, rather than shared.

In his ruling, Kennedy acknowledged differing religious convictions. Those persist today, not least in the Southern Baptist Convention, in which I was partly reared. Recently, delegates to the SBC’s annual assembly voted to work to overturn Obergefell, as part of an omnibus resolution on gender, sexuality, and reproductive rights.

The SBC’s non-binding resolution, “On Restoring Moral Clarity through God’s Design for Gender, Marriage, and the Family,” included the assertion “that we oppose any law or policy that compels people to speak falsehoods about sex and gender, and we defend the right of every person to speak the truth without fear or coercion.” So let me say the truth clearly: My marriage, formalized with vows made before God and according to the law of the land, isn’t just legal; it’s also sacred. It has made me a better Christian, a better family member, a better neighbor, and a better minister. I know love more deeply and completely now, and so am able to love better too.

The battle for marriage equality was just one small part of securing justice for LGBTQIA+ people. Legal inclusion has never guaranteed full belonging. I long for the day when a queer kid will grow up never doubting their belovedness, never worrying about hellfire, never questioning whether they have an equal place in society or the Church. So the work continues.

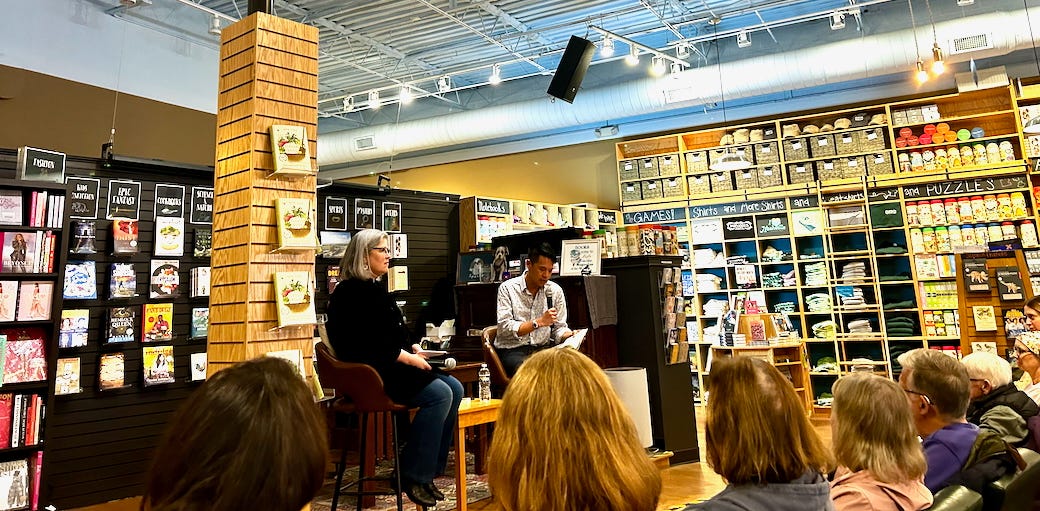

Good Soil has now been out in the world for three months—and I’m finally home after three months of book tour. It feels right to share some gratitude.

I’m so thankful for my conversation partners along the way: Barbara Brown Taylor, Amena Brown, Burkhard Bilger, Jamie Smith, Margaret Renkl, Sarah Bessey, Jen Hatmaker, Emily P. Freeman, Krista Tippett, Jacquelyn Mitchard, Kristin T. Lee, Kaitlin Curtice, Jia Lynn Yang, Mihee Kim-Kort, Lanecia Rouse, Kenji Kuramitsu, Chris Stedman, Byron Borger, and Shawn Smucker. Thanks, too, to guest musicians Spencer LaJoye, John Lucas, and Amanda Opelt. How wildly lucky I am that I get to count these extraordinary humans as friends and collaborators.

Publishers don’t pay for book tours anymore unless you’re super-famous, which I’m not. I saved up, used airline miles and hotel points, skipped meals and stretched that free hotel breakfast and heated up leftovers, and relied on the largesse of institutions, congregations, and individuals who offered honoraria, fed and housed me, and otherwise defrayed costs: First Pres in Berkeley, Calif., St. Luke’s Episcopal in Atlanta, Fifth Avenue Presbyterian in NYC, Westminster Presbyterian in Grand Rapids, St. Paul’s Episcopal in Chattanooga, Calvary Episcopal in Memphis, First Baptist in Austin, my beloved Crosspointe in Cary, N.C., Emmanuel Episcopal in Baltimore, St. Paul’s UMC in Kensington, Md., Rock Spring UCC in Arlington, Va., the First Presbyterian Church of Annapolis, Rockefeller Chapel at the University of Chicago, Trinity Episcopal in Asheville, N.C., Gloria Dei Lutheran in St. Paul, Minn., Willow Street Church in Willow Street, Pa., Solomon’s UCC in Chambersburg, Pa., United Lutheran Seminary, the First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, the Ashby and Passmore families, Erin Collier, Kenji and Brianna Kuramitsu, Werner Ramirez, Sharon Sampson, Jamie and Deanna Smith, Rebekah Sundsrud, and Winnie Varghese.

I’m grateful, too, to the indie bookstores that have hosted (or sold books at) events and advocated for Good Soil: Great Good Place for Books in Montclair, Calif., Charis Books & More in Atlanta, Posman Books in NYC, Schuler Books in GR, Parnassus Books in Nashville, The Book & Cover in Chattanooga, Novel in Memphis, Blue Willow in Houston, Book People in Austin, Fabled in Waco, Quail Ridge in Raleigh, N.C, Labyrinth in Princeton, Titcomb’s and Porter Square Books in Massachusetts, the Ivy Bookshop and Park Books in Maryland, Fonts and Book People in Virginia, 57th Street/Seminary Co-op in Chicago, Malaprop’s in Asheville, Beagle and Wolf in Park Rapids, Minn., Magers & Quinn in Minneapolis, Aaron’s Books in Lititz, Pa., Hearts & Minds in Dallastown, Pa., Nooks in Lancaster, Pa., which just posted an audio recording of last week’s book event, and Uncle Bobbie’s in Philadelphia. My work as an author would be impossible without the collaboration of booksellers.

Special thanks as well to Alisse Goldsmith-Wissman, my publicist at Penguin Random House, who went above and beyond in helping with logistics.

As you can see, I have absolutely not been alone in promoting Good Soil. (My sincere apologies to anyone I might inadvertently have omitted from the lists above.)

Most of all, thanks to the readers who have given this book their time and attention. Some people have liked it; others have not. Regardless, the choice to receive another’s story into one’s life is a gift to any storyteller. Thank you. (Especially if you did like it, though, I’d love it if you left a review on Goodreads, StoryGraph, or Amazon.)

Enough from me for one letter!

All my best,

Jeff

Well said re: What I'm Pondering. Celebration + staying in the fight. Some said in the years after: "We won! The end. All is good now. Liberation achieved. Why do we even need Pride anymore? The fight is over." which is so ridiculous, especially looking back from our viewpoint in 2025. We have to keep pressing forward each day.

Thank you for this Jeff. Beautiful review, and look forward to reading Rebanks again.