Postcard from the Philippines

Some fragmented thoughts on the pervasiveness of religion in Filipino culture, excellent ham, candid conversations, TikTok, and a prayer for these devastating days

Thursday, January 16

Siargao, the Philippines

I’m just finishing up a 10-day swing through the Philippines—the first leg of a reporting trip through Southeast Asia. Some of you know me best as an itinerant preacher or as a writer on spirituality. But one thing that makes the rest of my work possible is my career in journalism. In my twenties, I worked full-time at Time and Conde Nast, and I spent most of my thirties at the business magazine Fast Company. Today, I’m an editor at large at Travel+Leisure.

This kind of storytelling is my first vocational love. (I didn’t even preach my first sermon until the age of 38.) With my journalist’s hat on, I feel a bravery that I usually lack in the rest of my life. The journalist has permission to ask awkward questions—to be nosy—as well as the responsibility to be open to whatever answers might come.

On this trip, I’ve been surprised by the number of conversations I’ve had about matters of the soul. I’m here to do a travel story about the Philippines. I absolutely didn’t expect themes of faith and spirituality to emerge organically, again and again.

On my first night, the team at the (spectacular) Peninsula Hotel Manila organized a session of their Peninsula Academy, an educational program that emphasizes local culture and heritage. They took me to the studio of the fashion designer Len Cabili, whose company, Filip+Inna, celebrates the craft traditions of this wildly diverse country and boosts the economic fortunes of twenty-some Indigenous communities that work with her brand.

The creation of Filip+Inna “was really a faith journey for me,” Cabili told me at dinner. Some years ago, she was diagnosed with cancer. “Death became very real, and I started thinking, I’d better do something good if I get through this.” As she recovered and as she prayed, “the word ‘fashion’ would always come up,” she recalled. “God speaks to me through big words, and the word that kept coming up was ‘fashion.’”

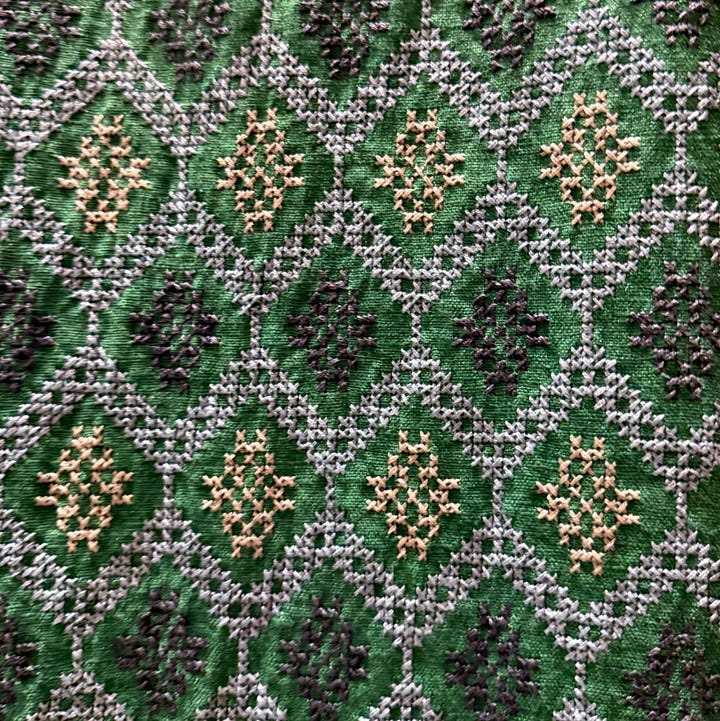

She began traveling the Philippines in search of Indigenous communities that had clung to their time-honored artisanal traditions. Then she created contemporary clothing featuring the Indigenous handiwork—say, a bomber-style jacket embellished by the elaborate embroidery of the Hanunoo Mangyan people, or a shift dress enlivened by the fine cross-stitching of the T’boli.

“A lot of times, I couldn’t see the next step, but I just put my faith in God to provide the buyers,” Cabili said. They came in droves, along with coverage from Vogue, Tatler, and Forbes. Today, Cabili’s workshop employs nearly three dozen women, many of them Indigenous. She has also created steady work for hundreds of others across the archipelago and helped to expand respect for the Philippines’ rich and varied heritage. “This culture needs to be celebrated, but how can we celebrate, or even preserve, what we don’t know?” Cabili said. “Sometimes our culture is so masked by the Western. This is a way to showcase our craftsmanship.”

Cabili isn’t unique in seeing her faith as backing material for entrepreneurship. On our second day in Manila, we did a tour of the old colonial city center, where only one of the seven churches, San Agustin, survived the devastation of the Battle of Manila during World War II. Then we wandered through Chinatown and to the neighborhood of Quiapo, where we stopped at a shop called Excelente Chinese Cooked Ham for a snack. We bought a couple of sandwiches (150 pesos each, about $2.50—a real bargain), and as we sat in the shop eating—the ham was indeed excelente—the proprietor, who introduced herself as Nene, came over to talk.

Excelente was actually her husband’s family’s business; they’d made ham for generations, even before immigrating from China. She married into ham-making after meeting her husband on a plane. “I was a flight attendant,” she said with a grin.

Entirely unprompted, she said she attends early Mass every single morning, then comes to the shop “to look after the girls,” she said, waving a hand at her employees. She stopped to tell them to bring us some drinks. Then she asked if we wanted some cheese. Before we could say yes or no, squares of banana leaf-wrapped kesong puti, a cheese made of water-buffalo milk that tastes like a cross between burrata and feta, had appeared. She continued her rangy monologue, recounting the hardship of her own mother’s life and the responsibility she feels. “I do my morning prayers every day,” she said. “I think maybe God put me here.”

My friend Tesa Totengco, a Filipino-born, New York-based travel advisor who put this itinerary together, wanted me to experience some of Manila’s robust contemporary-art scene. So the next morning, we visited the private collection of a wealthy businessman before proceeding to a few contemporary-art galleries. Again and again, I saw religious imagery and spiritual themes.

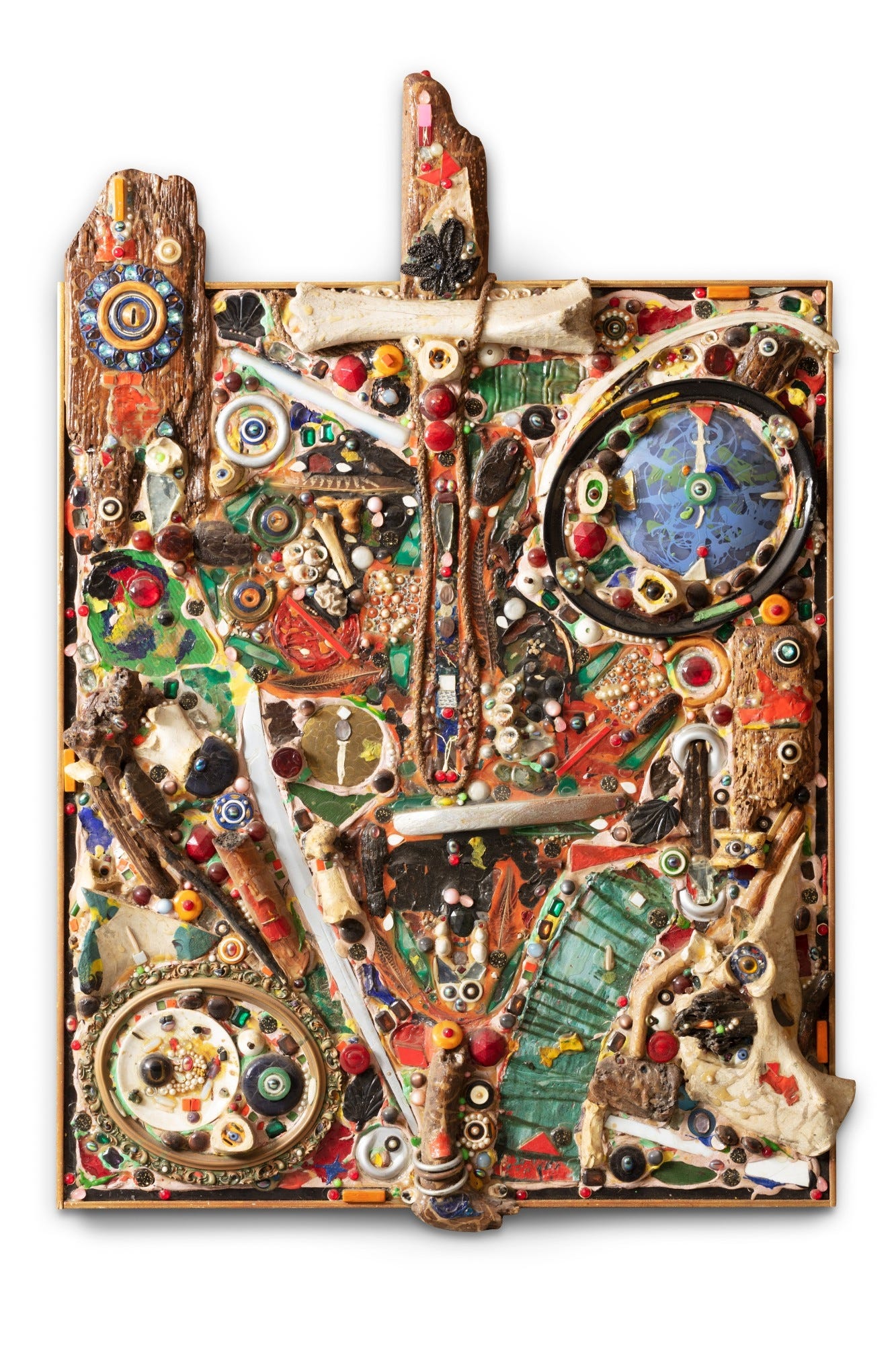

There was an obvious cross at the top of Alfonso Ossorio’s 1963 mixed-media piece “The Hanging.” “He was a friend of Jackson Pollock’s, he was gay, and this one is quite interesting because you can see that he’s a tortured soul,” said curator Bambina Olivares, who accompanied us on our tour. “It’s very disturbed.”

At Tina Fernandez’s Artinformal Gallery, we saw some work by the young painter Ryan Jara, including a painting that had images of Pope John Paul II, Mother Teresa, and Joan of Arc. But we also glimpsed more subtle wrestling, including a beautiful, massive print by Tosha Albor. In the notes for that work, Albor writes, “I’m currently exploring the concept of wholeness and what it offers to my sense of self. How does it feel to be whole? What are the sensations, tension, conflict, or fantasies that bring me to it, or prevent me from getting closer?”

Then, at the Gravity Art Space, I fell into a conversation about the intertwining of faith and art with Indy Paredes, the artist who runs the space, and Silke Lapina, a German-Filipina artist who was visiting. “We have so many esoteric beliefs here,” Paredes said. He thinks it’s natural that those beliefs should be explored on the canvas. Lapina, who is deeply interested in theological questions, said she felt that was more accepted in the Philippines than in Europe: “When I arrived, I thought, Oh my god, I can actually talk about all my topics here. I say a prayer before I start my work, and I’m not ashamed to say I pray.”

“Religion really shapes the Filipino psyche,” Olivares told me. That is undoubtedly true—and the story of religion here is inevitably bound up with the story of colonization. The Spanish conquest in the mid-16th century also brought mass conversion to Roman Catholicism. In recent decades, the Catholic Church here, as elsewhere, has been plagued by scandal and abuse. Still, about 80% of the population remains Catholic, and though the Philippine constitution enshrined separation of church and state, Maundy Thursday, All Saints’ Day, and the Feast of the Immaculate Conception of Mary are all still public holidays.

The artist Wawi Navarroza told me that one core aspect of the “postcolonial condition” in the Philippines is hybridity. I’d go further and say there’s a comfort with discomfort and dissonance. Navarroza tries to capture some of it in her colorful, complex photographic work, which she calls “tropical gothic”: “It’s all fluid. It’s never just one thing. Our strength comes from things that maybe don’t make sense at first—the contrasts, the contradictions, the absurd. It’s cacophony. It’s muchness. It’s layers.”

At dinner with Navarroza and some other artists and gallerists one evening, I experienced that muchness, that layered way of life, in beautiful display. One person talked about how she became an atheist while another mentioned that she had found solace in the ritual and the mystery of the Latin Mass. People recounted their school days—the strictures of the uniforms, the attitudes of the nuns, the little rebellions as the students fought their way toward adulthood. They talked freely about how they made sense of religion, or didn’t, and what they had hung onto, or discarded.

“You can’t get away from commenting on religion here. It’s pervasive,” Fernandez, of Artinformal, told me at that dinner. What struck me most, though, was the apparent lack of judgment at the table—and indeed throughout so much of my time here in the Philippines. Though there has been no shortage of heartache in the testimonies, the conversations have felt apolitical and somehow less fraught than what I’m used to in the U.S. Why?

I’ll continue to ponder that question as I leave the Philippines tonight. It feels too pat to say that so many centuries of building resilience has enabled these folks, even those who have been deeply hurt by institutional religion, to talk about faith and values in a wholehearted, candid, and brave way. But it also feels right to name that, in addition to their embrace of contradiction, they seem well-equipped with a thing that’s so needed yet all too rare in our world: grace—for ourselves and for others.

What I’m Reading: Nearly to the end of Roxane Gay’s outstanding, perceptive, chastening examination of TikTok, I came to three taut, powerful sentences: “We want. We want. We want.”

Full disclosure: I’m not on TikTok, and I intend never to be on TikTok. I have significant concerns about the Chinese government’s involvement, and I don’t need yet another online black hole to alter my life with its insatiable gravity. But don’t mistake that small choice for a larger claim to any kind of moral high ground: You’ll find me on Instagram, and to a lesser degree, on Facebook, and Gay’s insights largely apply to the other social-media platforms too.

“TikTok is creative and sprawling and often strange and anarchic, which mirrors the internet more broadly,” Gay writes. I’d argue that it also mirrors our world. In spending time on TikTok and its social-media siblings, many of us give away more than our data, and our time, and our attention. On these platforms—that word matters so much—we, creators and consumers alike, reveal who we are and who we wish to be. “It’s incredible to witness how many different ways there are to be, how creative (or uncreative) people are, how we crave attention, hoping that if we make the perfect video, we might be catapulted to some version of fame,” Gay writes. “It is also … haunting, how so many of us yearn to be seen, to be understood.”

Yes, I’m on a reporting trip that has taken me to some spectacularly beautiful places, but I obviously haven’t forgotten about the devastations that are happening elsewhere in the world. Yesterday, I wrote and shared a prayer with the Evolving Faith community that I offer here, in case it’s helpful to you.

O God who was present to the wandering people through steady flame, we pray for an end to the fire that destroys and devastates and the beginning of the fire that warms and nourishes. Be with all who mourn. Give them the hope of renewal and restoration.

O God who sends the gift of rain, we pray for the water of life. Deliver what we need. Move the heavens, such that they bless us with reminders of your provision.

O God who promises to be with us through whatever comes, show yourself now. How can we be encouraged along paths of peace rather than the way of violence? What will it take to usher us toward goodness, not destruction? Why do we persist in our selfishness instead of communal care? How do we honor truth in a culture of lies?

O God who pledges your solidarity, remind us of the lessons of Emmanuel. Guide us to a posture of openheartedness, vulnerability, and love.

O God who has embodied faithfulness, be our solace and our strength. Give us the courage to hope and the audacity to persist.

Amen.

What’s on your minds this week?

Always grateful for your companionship on the journey.

Yours,

Jeff

There’s something refreshing and centering about all these threads of travel and culture, spirituality and work, place and history. You’ve woven them together in an organic manner that I believe grounds us with authenticity that I find often dismissed by our American mainstream culture. Your prayer is “icing on the cake.” Thank you for this welcome gift.

"Move the heavens, such that they bless us with reminders of your provision." Thank you for this prayer, and the post. This line really stood out to me - I've been thinking and writing about the motions of stars and planets, and their hidden reminders of God's faithfulness even beyond the sky & clouds. The moon crossed in front of Mars a couple nights ago, and it was bitter cold but amazingly clear here in Chicago. What joy to see those bodies collide, what a reminder of his provision. Move the heavens, oh Lord. Then again, often the movements of those cold bodies feel more like absence than provision: then too: oh Lord, move the heavens today, that we might know you.

Thanks again!