Preparing the Feast

Some fragmented thoughts on learning to eat fufu, being in the kitchen, Jesus cooking for his friends, failed Yorkshire puddings, and transformation amid COVID-19

Thursday, April 8

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Hello, dear reader.

When I was 21, I spent the summer volunteering at a rural not-for-profit based in Cape Coast, Ghana. I stayed in a local family’s home for over a month, and, because the dad of the family was overseas studying for the entirety of my visit, I was the only adult man in the house. Note: It’s questionable whether I was really an adult, but legally and for the purposes of this story, I was.

The three women of the house, along with the three kids, ate in the kitchen. Every morning and evening, I sat alone, at the head of a long, plastic-covered table that had room for eight, maybe ten people. Every morning and evening, like some unwitting monk, I took my meals in silence, save for the fluorescent light’s hum overhead and the women’s laughter and chatter, which filtered through from the kitchen.

On my third or fourth night in Ghana, the women declined to set the table with the fork and spoon they had provided the previous evenings. It was time for me to learn to eat the correct way, I was told: “The food will taste better!”

One of them hovered by my side, hands on hips, issuing instructions. With the fingers of my right hand—“the left hand is for dirty things!” she said—I was to break off morsels of fufu, the boiled and pounded cassava and plantain dough that we had at most meals, and use them as delivery vehicles for light soup, a tomato-and-pepper-infused broth that often featured fish and, occasionally, if they felt like spoiling me, goat meat.

Dinner took a long time that night. Even in the subtropical warmth, the soup, which started out scalding, couldn’t hold its heat long enough for me to eat it. My fingers turned pruney before I was even halfway through the meal, and more soup splattered the table and my T shirt than seemed to make it to my mouth. The woman’s constant giggles added a lilting soprano line to the overhead bulb’s bass-line buzz.

A few days later, I heard the steady thump of the giant, wooden mortar that they used to pound the fufu. So I quietly knocked on the kitchen door, and one of the women granted me entry. They all stopped their work and stared at me for a long moment. Finally, the one holding the mortar sized me up, flicked her chin at the boiled cassava, and asked, “Do you want to try?”

I wasn’t ready for how heavy it was. I couldn’t figure out how to get a good grip on the wood, which had been worn smooth with years of use. And as I flailed, often barely even making contact with the cassava, the women laughed uproariously. They tolerated my presence for a few more minutes, and then they ushered me back into the dining room and never allowed me into the kitchen again.

I understood: The kitchen was their space, not mine. There’s something sacred in knowing when you’re not the host and in playing the part of the faithful guest. Hospitality is like storytelling. Just as it’s as vital to understand how to receive a story as it is to offer one up, it’s as important to know how to be hosted graciously as it is to know how to host.

Yet in every home I’ve ever visited, I’ve always wanted to be in the kitchen. When I was growing up, holidays were always marked by the whir of activity around the stove and the sink. During the Thanksgivings and Christmases of my childhood, the men stared at the TV in the family room while the women made a true family room in the kitchen—trading stories about the relatives in Hong Kong and England and New Zealand, tending to giant pots of soup burbling over the gas flame, and making quick work of both animal and vegetable with the rapid chop-chop-chop of the cleaver.

In the kitchen, I felt I could breathe. And there was so much to inhale: the savory steam escaping the soup pot, the rich scent of lacquered duck crisping in the oven, the memories and news reports of a scattered clan. I was drawn, too, to the danger, whether it was the sharp blade of a heavy knife, the dancing blue flame under the wok, or the roiling, boiling water in the pot. Risk brought beautiful transformation.

Maybe that’s what I love about the kitchen. It’s dynamic. Arguments might erupt—“I’ve never seen it cooked that way!” can be an invitation or a grenade. But bonds strengthen too, and in the company of others, something comes to life that could not have been on its own. What was raw becomes gentled, the hard turned tender, disparate elements harmonized. Flavors meld.

Recently, I was re-reading one of my favorite stories in all of Scripture—a post-resurrection story that seems right for Eastertide contemplation. In John 21, some of the disciples go fishing, but their nets remain empty. After dawn, they see a man standing on the beach. They get to chatting, and he gives them what few fishermen want—unsolicited advice. He tells them to cast their net on the starboard side. They do so, and within moments, the net heaves with fish, so many that they can’t haul it in.

Recognizing Jesus, Simon Peter swims toward him, while the rest of the crew follows in the boat, dragging the net. Ashore, they notice that Jesus had been preparing breakfast—bread’s hot and fish grilling. Come and have breakfast, he says. I imagine that he beckons them with all the tenderness of a friend who knows what his beloveds have been through—the rumble in their stomachs, the heaviness in their hearts. Nothing needs to be said, because it’s just known. They are known.

One detail I love: Jesus asks the fishermen to bring some of their fish to him, to add to the fire. I seriously doubt Jesus would have prepared a picnic without sufficient supplies, given his mystical pantry (fishes and loaves, remember?). Instead, I read an invitation here—a suggestion that what we have to bring matters too.

I wonder why I’ve never heard anyone preach a sermon about Jesus cooking for his friends—or about cooking at all. Why do we fixate on consumption—on eating the bread and the wine, on all the times Jesus sits at the table with all manner of dining companion—and so little on preparation? Somebody had to bake the bread. Somebody had to make the wine. Why do we so rarely glimpse the bakers and the vintners?

You all know I love contemplating the theology of the compost, which is its own form of preparation and transformation. I’ve been thinking more lately about the theology of the kitchen. What might we glean from the stories of the biblical figures who stewed and roasted the meat, who prepared fig cakes, and who set the table so that others might feast? What might we learn from them? What would they have to tell us, if only we could eavesdrop on their kitchen?

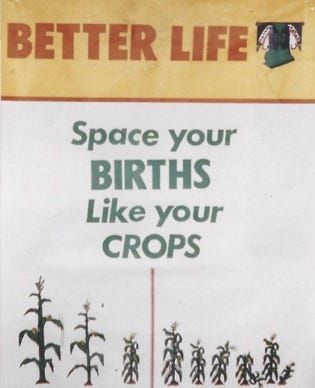

What I’m Growing: While I was digging through old pictures from my Ghana summer, I found one of a poster that was up in the nonprofit’s office. Yikes!

My tomatoes are growing! I’ve got two plots in the community garden this year—two 25x25 pieces of dirt—and I’m determined to be more diligent about the weeding, mulching, and tending. But first, I have to have something to plant, so I’m cheering this little ones on. Oh, and I planted eight or nine varieties? But I forgot to label them. So… I guess we will know them by their fruit.

What I’m Cooking: Obsessing about food is fun for me, but I make tons of mistakes. For Easter Sunday dinner, I roasted some beef (the Serious Eats reverse-sear method works well), which went with potatoes Anna (Geoffrey Zakarian’s recipe, except with a bit less butter) and Brussels sprouts (pan-roasted, with maple syrup and sriracha). We paired it with a Bel Tramonto, a Sangiovese-Merlot blend, from Mari Vineyards, a wonderful winery on Michigan’s Old Mission Peninsula. (Eat local! Drink local!)

We were also supposed to have Yorkshire puddings, which are supposed to be crisp-on-the-outside, pillowy-on-the-inside works of wonder. Here’s how mine turned out:

Tristan said the flavor was good. I love him, but they were flat, dense, doughy, and not good at all. I suspect the hot fat wasn’t hot enough, and I know I used too much whole-wheat flour. Serves me right for trying to be healthier. These were not my first Yorkshire puddings, but they were definitely my worst.

More successful: The pasta with fried lemons and chili flakes we had for dinner on Tuesday evening. Tuesday was a 78-degree day here, so we wanted something light, vegetarian, and summery. One change: We did casarecce, a fun, twisty shape that holds the sauce well, not spaghetti.

What I’m Reading: Over at the New York Times, Elizabeth Dias and Audra Burch put together a moving package about transformation amidst the pandemic. Sometimes the best reporting means just letting people share their reflections and tell their stories. I’d like to believe that Elena K. Cruz of Washington, Mo., was right when she said: “The pandemic scraped away all facades we’ve built around our lives.” And then there’s the heart-wrenching account by Joelle Wright-Terry, a hospice chaplain in Michigan, who said, “I know I am becoming someone different. I just don’t know what that different will be yet. I know I was a wife. And now I am 47 years old and a widow.” These testimonies prodded me to think about what’s changed in me and what invitations there might be tucked amidst all this loss. And now that I’m sounding like my spiritual director, I’m super-irritated at both her and myself, so I should just cut my losses and commend this beautifully quilted piece of storytelling to you.

If you have any suggestions for who has written books or articles relevant to a theology of the kitchen, I’d love to know! I’ve already read Robert Farrar Capon’s “The Supper of the Lamb.” Anything else you can recommend? By the way, when I talk about “theology,” I don’t mean only academic theology; I use the term more broadly, to encompass the ways in which we try to understand God and God’s work in the world. Any other thoughts on my notion of a theology of the kitchen? Please share!

I’m grateful we can stumble through all this together. I’ll try to write again soon.

Yours,

Jeff

Kitchens are safe haven for introverts. No eye contact necessary, busy hands, tiny respites from conversation to focus intently on chopping, ability to walk away from chitchat to fetch a pot...just perfect amount of human interaction for us.

Looking over the reading recs that have been shared so far, it strikes me how many of them are written by women and how few by men. Maybe this is another indication of how theology has long been seen as a field for men and the kitchen so often as a space for women, hence the disparity.