The Gospel According to Eeyore

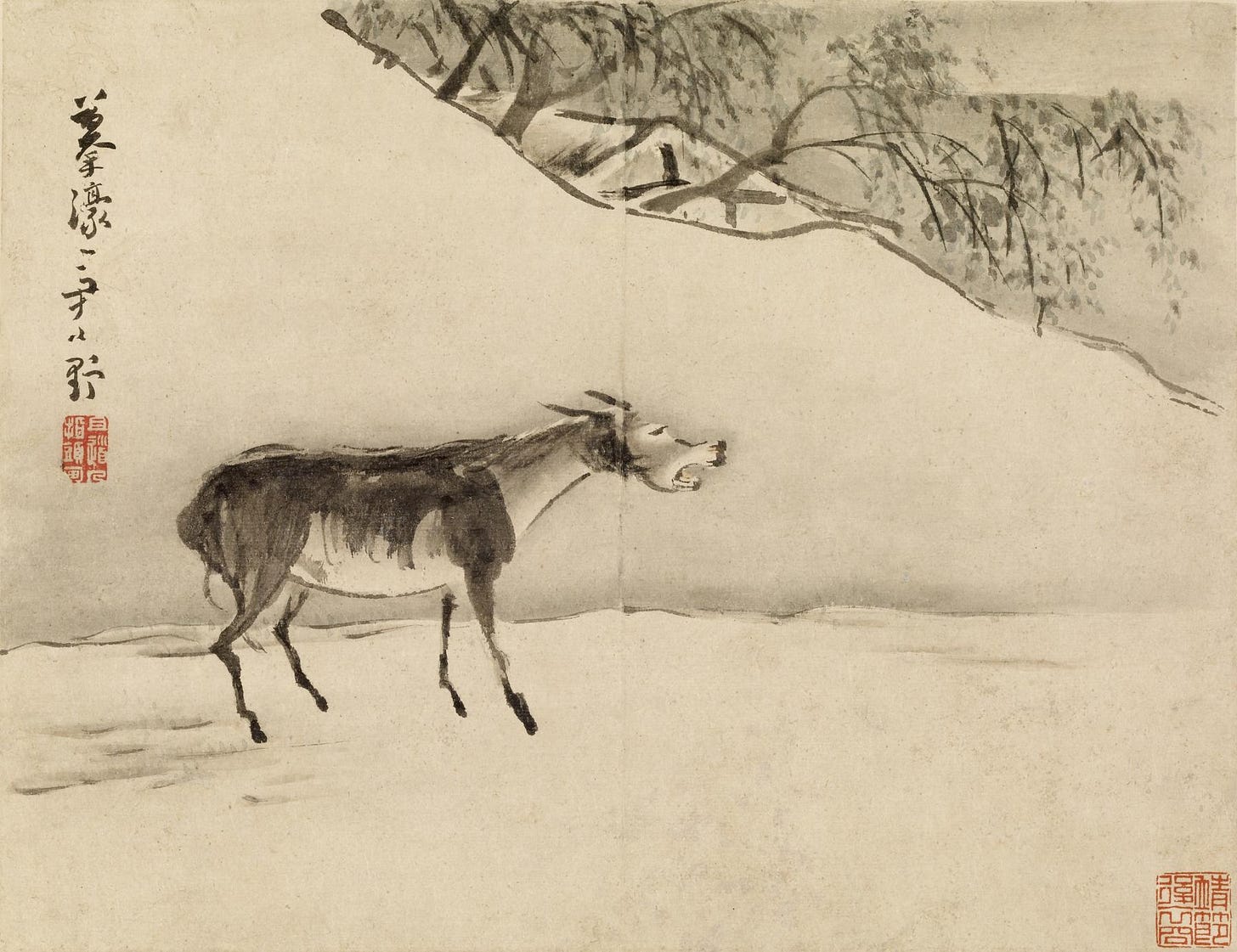

On this Palm Sunday, I'm thinking once again about the donkey

Years ago, when I was a seminary intern, I preached a Palm Sunday sermon about the donkey. It remains one of my favorites, and I offer it to you in its entirety today in the hopes that it will bring some nourishment and some hope as we enter Holy Week.

Much love,

Jeff

—

When I was young, I discovered one of my spiritual gifts. Some kids were good at making others feel loved. Other kids cornered the market on joy. My specialty unfolded on the family-room couch, where I could spend hours refining my gift: the throwing of the pity party, also known as wallowing in your own angst.

Many people do not discover this gift until they're teenagers, but I guess I was precocious. But I wasn't alone. These were pity parties for two: I had a stuffed Eeyore, the famously dour donkey from the Winnie the Pooh books. He was a kindred spirit.

The donkey Eeyore is the sad sack to Pooh Bear’s winsome, happy-go-lucky self. Where Pooh sees joy in a pot of honey, Eeyore sees sticky mess. If Pooh is sunshine, Eeyore is rain. Where Pooh wanders the world blissfully ignorant to what he’s missing—did you ever notice that in the Disney movies, he’s never wearing any pants?—Eeyore knows what he lacks—in one story, he lets everyone know that he's missing his tail—and he engages in the theological practice of lament.

One day, the boy Christopher Robin greets Eeyore. “How are you?” Christopher Robin says. “It’s snowing still,” says Eeyore gloomily. (After our fourth nor’easter in as many weeks, even the optimists among you get that glumness.) “So it is,” Christopher Robin says. “And freezing,” Eeyore says. “Is it?” Christopher Robin asks. “Yes,” Eeyore replies. “However,” he says, brightening up a little, “we haven’t had an earthquake lately!”

Where other people saw melancholy, Eeyore and I saw clarity. Where others read pessimism, Eeyore and I read humble reality. Where others felt the shadow of clouds, Eeyore and I felt we weren’t blinded by sunshine—we could see a way forward, a hopeful way, because it dealt with our true condition.

I thought of Eeyore as I explored this morning's Gospel text. I wondered if there were some lessons for us in how he moves through the world—and indeed how the Biblical Eeyores, Scripture's donkeys—take on the tasks to which they have been called. Clear-eyed. Humble. Sure-footed. Obedient. Could we learn something from the way of the donkey?

You might at this point be questioning my word choice. Did God call donkeys to service? Go back with me two thousand years, to a historical moment in which a holy donkey plays a pivotal role. Close your eyes, if it would be helpful, to imagine yourself amidst the scene, just outside the city walls of Jerusalem. The air is a little dusty, from the dirt of the mostly unpaved roads, but it’s crisp; it’s springtime.

You have heard that there’s this man Jesus who performs miracles, including raising his dear friend Lazarus from the dead. Now he is coming to Jerusalem, along with so many others, just before Passover, the greatest feast of the year, when you remember how God brought your ancestors out of Egypt, out of slavery, out of oppression, so many generations ago.

You’re hoping for liberation too, because remember, you are living under Roman rule. The Romans are not kind rulers. They are tyrants and oppressors. You feel the burden of surviving under a regime that seems not to care at all about your welfare. Your religion promises a Messiah, a savior, and you cling to that promise. You have to believe that a new King is coming, a King who will love you and your people, a King who will restore your freedom. What if this man Jesus is that King? What if?

As Jesus approaches Jerusalem, you might be riding waves of excitement. People start clambering up the palm trees and tearing off fronds and waving them at the parade. We want to believe in Jesus, they say. We need help. “Hosanna! Hosanna!”

We may hear “hosanna” now as a shout of praise, but back then, it wasn’t. It’s a short form of a Hebrew phrase: In Psalm 118:25, the psalmist cries to God, “Ho-shi-ah-na-ah-na”—which translates roughly, “Save me now, I beseech you!” “Hosanna” is a plea for rescue. “Hosanna” is a desperate call for liberation. “Hosanna” is what we cry out to God when we don’t have words to explain our pain, when we don’t know a way forward.

Many people around you are waving palm fronds at this Jesus, as much to get his attention as to honor him. Where do you see yourself amidst these crowds, amid the green leaves against the warm yellows of the Jerusalem stone? They want his help. They want what healing he has to offer. Do you?

This isn’t the 1st century equivalent of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade—this is more like a protest march. As the procession moves along, the wide ways outside Jerusalem surrender to the walls and the narrow, ancient city streets within choked not just with marchers but also venders and people going about their business. There are pious disciples and angry Pharisees and curious bystanders: Do you see yourself in the whipped-up crowd, shouting, “Save me,” and hoping for liberation? Are you just trying to run your errands, so you’re irritated by the inconvenience of the parade? Are you too dignified for all this, too respectable for the chaos, so you hang back, tucking yourself into a niche in the city walls or a doorway perhaps—but in the thoughts of your heart, yes, you’d like to see yourself on the side of this Jesus? Especially those of you who are elders, deacons, and pastors: are some of you more establishment types? Maybe you just got out of the Pharisees’ equivalent of a Consistory meeting and you’re troubled by this rule-breaking insurrectionist.

Wherever you see yourself in this story, I want you to pause to consider the one character who consistently gets overlooked: the donkey. The donkey who carries Jesus through the crowd, the donkey who bears the good news step by step, the donkey who seeks sure footing on the uneven pathways, the donkey who humbly submits to its place on this difficult journey. The donkey is worth a listen. This donkey is the surprise.

Society has consistently denigrated and underestimated donkeys. Philo and Plutarch both called the donkey “the stupidest of the beasts.” Aristotle commented on its foolishness. It’s largely Shakespeare’s fault that “ass” became a slur; in Midsummer Night’s Dream, the mischievous Puck makes a literal ass out of Nick Bottom, giving him a donkey’s head. Even in Winnie the Pooh, Eeyore is often the butt of the joke.

The horse is usually the hero—regal, majestic, riding to victory. The Roman cavalry that conquered ancient Israel was an army of horses. And if Jesus is the Messiah, if Jesus is liberator and conqueror, maybe Jesus should have been atop a regal horse.

Yet, as ever, Scripture flips the script. Throughout Scripture, the horse is described as a swift, powerful four-legged weapon of domination and war. It often represents the oppressor. The psalms tell us that horses signify “vain hope for victory.”

The donkey is essentially the non-horse. It is usually depicted in the Bible as a carrier of truth and a bearer of peace.

The donkey is one of just two animals in Scripture with a speaking role. If the serpent is devious, the donkey is true. There’s a story in the book of Numbers about the prophet Balaam who rides a donkey. The donkey doesn’t seem to follow Balaam’s instructions, constantly veering off the path. What the donkey sees and what Balaam can’t is an angel of God, blocking the way. Balaam is blind to what’s happening, but the donkey sees. Three times before God opens Balaam’s eyes to the full picture, Numbers 22 tells us, “the donkey saw.” When God opens the donkey’s mouth, it tells Balaam of its holy perspective.

1 Samuel has another donkey story, in which a woman named Abigail urges King David not to launch a bloody battle. She loads her donkey with bread and wine, the very elements that later, in our tradition, will come to symbolize the life we have through Jesus. Abigail successfully convinces David not to go to war.

Some commentators argue that Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem on a donkey echoes King Solomon’s parades. They point to translations of the Old Testament that describe Solomon and before him, his father David, riding royal donkeys. But this isn’t quite right. The Hebrew texts say that David and Solomon rode mules—half-horse, half-donkey, mules carried the symbolism of both war and peace, battlefield glory and hard-won comfort.

But Jesus chooses to go donkey-only. No war, only peace. This is a different kind of king. This is a king who, according to our tradition, had been heralded hundreds of years earlier by the Prophet Zechariah; Zechariah chapter 9 says: "Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on a donkey." This is a Messiah who, in his parable of the Good Samaritan, again makes the donkey an animal of healing: It’s a donkey onto which the Good Samaritan puts the injured man. It’s a donkey that carries the sick soul to safety and security.

But the crowds misperceive, as do the disciples. They want an earthly king, a temporal Messiah, someone to rescue them from their colonizers. “Hosanna! Hosanna!” they cry. “Save us! Save us!” And Jesus slowly makes his way through this crowd, atop a surefooted, indefatigable, but unmistakably lowly donkey.

Over and over in reading Scripture, we overlook this lowly creature, this unsexy half of the mule. Over and over in our own lives, we look to the beautiful, glamorous, and powerful for lessons. But I wonder: What if we’re supposed to be more like the donkey? What if we're supposed to be more humble, obedient, eyes focused on navigating the uneven terrain? What if we're supposed to devote our entire being to fulfilling our calling? What if it is our bodies that are meant to convey the good news of Jesus? What if we are called not to shout hosannas or wave palm fronds but to bear Jesus himself into the world?

We live in a land where we’re particularly good at shouting hosannas and waving palm fronds, which in and of themselves aren’t bad, but without accompanying action, does little more than stir the air for a few seconds. We live in a land where the name of Christ is proclaimed at football games and thoughts and prayers are offered during days of tragedy, yet when the time comes for more than platitudes, when the call comes to offer our selves—our prestige, our comfort, our bodies—for the Gospel’s sake, we scatter to the four winds. We live in a land where, too often, we are, across the theological spectrum, the haughty establishment who rather enjoy what power we have and reflexively explain why things can’t be done.

Who are the holy donkeys among us? Who are the people who put their lives on the line for the Gospel, people who with their bodies carry the King’s good news into our midst, only to be undervalued, even ignored? I think of caregivers and mothers, aid workers and missionaries—holy donkeys in so many homes and places. I think of our black brothers and sisters, who have for so long been the holy donkeys to white America’s Balaam, calling us to halt our sinful path even as we proceed foolishly and violently. I think of peacemakers and healers, young people marching against gun violence and humanitarians toiling in ravaged Syria, the holy donkeys who carry us nourishing bread and life-giving wine, even as our leaders prefer warhorses and weaponry. I think of my queer siblings, the holy donkeys who with their very lives testify to God the Father’s creativity, the Son’s self-sacrificing love, and the Spirit’s resilience—loving when they have not been loved, refusing to shame because they have been shamed, bearing the physical burden of their difficult call to costly grace.

Friends, as we depart Lent, enter Holy Week, and look toward Easter, let us meditate on the example of the donkey who, in Jesus, found its greatest purpose.

Let me close with a little exegesis of another story from the House at Pooh Corner—the rest of the story, actually, after Eeyore and Christopher Robin discuss the weather. The snowstorms have destroyed Eeyore’s house. He finds himself wandering, not sure where to go. He is a donkey in search of a way forward.

Unbeknownst to Eeyore, his friends realize his plight. They build him a house. When he finds it, he feels not just relief but also deep satisfaction. “It just shows what can be done by taking a little trouble,” Eeyore says. “Look at it! That’s the way to build a house.” Honestly, this house doesn’t look like much by the world’s standards—it’s just a ramshackle collection of sticks. But it’s a palace to Eeyore. Shelter from storms. A place of belonging.

Jesus does for us what Eeyore’s friends do for him—offering the safety and belonging we seek and the home base from which we are to radiate his love to the world. We are called to the life of the holy donkey. In Jesus, we find not just safety and belonging but also a path forward. In Jesus, we are called to walk a way, together, that may not be easy, that may not be all sunshine and rainbows, but that is humble and true and real and that leads to ultimate hope. This is the way of the donkey.

This call is for you, church, individually but even more so together. In Jesus, you have, like the Biblical donkey, received a call: to carry the good news into the world, to proclaim God’s peace, to love God and one another and your neighbors better. You may be tired. You may be weary. You may be battle-worn. You, individually and as a congregation, may feel like you’re struggling with a season of uneven pathways and rocky terrain, but with the holy donkey’s spirit, you can live into your call.

The way of the donkey is a humble way, a countercultural way, sometimes a difficult way. But as our Scripture exhorts us, “Do not be afraid! Look, your king is coming!” This way is ultimately more beautiful than anything else this world can offer, because of that King. It is the way of grace, and it is the way of love, and Jesus promises He will be with you all along that way, never letting you go and cheering you on and even giving his life for you and then conquering death itself—for you. He is for you, and He is with you—with every breath, with every step of the way.

Thank you for this. A family member has called me Eeyore for much of my adult life. It has not been meant as a complement. Yet, Eeyore has long been my favorite Pooh character. Your words bring peace and clarify purpose. Thank you. I think, when we have been burdened with seeing truth, seeking justice, living in kindness and hope, life doesn't look like all sunshine and rainbows. We see pain. We see injustice. We see lies and what they do to humankind. The glass is not half full. The glass is not half empty. There is liquid in the glass. It takes a stubborn sure-footed persistent and steady beast to carry that load. It is burdensome at times. I'll take Eeyore any day.

Thank you. Simply beautiful.