Vows

Some fragmented thoughts on my impending ordination, impossible promises, heroes of the faith, worms, and dresses

Thursday, April 4

Brooklyn, N.Y.

I arrived on the East Coast yesterday ahead of my ordination on Saturday. If you’re here for theological inquiry, book reviews, or garden stories, I have none of those this week. Instead, please indulge me a personal reflection as I prepare to take my vows.

Recently, people have repeatedly asked how I feel. I’ve mostly said that I’m trying not to have feelings, because there is a lot to do. Anyway, I’m often unsure if they want—or have time for—the honest answer. Is this just a spin on the perfunctory “How are you?” Do I practice my ministry of mercy on them, or do I unleash my whirlwind of emotion? Usually I try to restrain anything beyond a gentle breeze.

I entered the ordination process in the autumn of 2016. The outcome was never guaranteed—and it shouldn’t have been. My understanding was that my concentric circles of community would ask big questions with me: Was I called? Were my gifts suited to this work at this moment in the life of the church and the world? If so, how might that look? That’s why it’s called a process, and that’s why it’s supposed to be an extended season of discernment.

It’s been fascinating that so few people have actually been willing to engage these questions at much depth. “Of course you’re called,” I’ve heard again and again. A surprising number of conservatives have told me that, while they’re generally opposed to the ordination of married queer people, they feel I’m called to ministry, even though they can’t and won’t publicly say so. More so, this process has been drawn out because of my denomination’s own discernment on matters of sexuality, although I’d argue that “discernment” is a very polite way for a ping-pong ball to describe the actions of the paddles on either side.

This season has turned out to be longer than even I had anticipated. Though I expected that it would not be the usual three years, I never thought it would take the better part of eight. It’s as if I started out on a day hike and ended up on a camping trip. I like hiking; I hate camping.

--

A longtime friend recently described my ordination as “your wedding to God.” I didn’t know whether to laugh, to cry, or to cringe—perhaps all three. The notion of getting married to God is all kinds of awkward and problematic, and I encourage you not to examine the metaphor too closely.

There ought to be a fidelity to ordained ministry, though, that’s akin to that of marriage. On Saturday, I will “pledge my life to preach and teach the good news of salvation in Christ, to build up and equip the church for mission in the world, to free the enslaved, to relieve the oppressed, to comfort the afflicted, and to walk humbly with God.”

This promise is wild. Just as it is impossible for those who are marrying to understand precisely what their vows mean in practice—twelve years in, Tristan and I are still learning—there is no way for ordinands to comprehend exactly what they’re getting themselves into when they make such a commitment to God, the church, and the world. The vows express intention, but one necessarily makes them with naïveté—varying degrees, sure, but naïveté nonetheless. I can say that I will walk humbly with God, but where exactly will we be walking? As I survey this woebegone world, I wonder, What kind of mission could possibly offer the healing it needs?

A few weeks before his ordination in 1931, Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote to a friend about the dire state of his country and the world. “But will our church survive another catastrophe?” he wondered. “Will it not reach the end of its existence then, if we do not change immediately, speak and live completely differently? But how?”

Bonhoeffer admitted that he wished sometimes that he could escape to the countryside, “to get away from everything everyone wants from me and expects of me. It’s not that I’m afraid of disappointing—at least I hope not primarily—but that sometimes I simply cannot see how I will be able to do all these things right.”

He anticipated that well-meaning folks around him would say simply that he ought to do his best. “The cheap consolation that one just does what one can, and that there are others who would do it even worse, isn’t always enough,” he wrote. “Now and then, I would like to laugh grimly about all of that.... And in times like these! What good is a person’s theology?”

Nearly a century later, I echo Bonhoeffer’s grim laughter, and I confess that I share his questions: What exactly is the church doing? What is my part in the larger story? How could I possibly play that part well? And indeed, in times like these, what good is a person’s theology?

--

I’m not much for heroes, but I do have a few. One is the late Rev. Florence Li Tim-Oi. During World War II, the Hong Kong-born Li ministered to refugees in Macau, which had no resident Anglican priest. In January 1944, Ronald Hall, the Bishop of Victoria (Hong Kong), ordained her so that she could administer the sacraments to the flock in Macau. Li became the first woman ordained a priest in the Anglican Communion.

Hall’s decision was thoughtful, creative, and hugely controversial. Called to account for his action, Hall told his superiors in England that “no prejudices should prevent the congregations committed to my care having the sacraments of the Church.” He was lambasted publicly in the Church Times, which wrote that he “neither considered the wider implications of his action, nor consulted wiser heads than his own. He preferred to play a lone hand, not like a civilized leader who is himself subject to constitutional authority, but like a wild man of the woods.”

In 1946, under pressure from the Archbishop of Canterbury and China’s Anglican bishops, Li faced a choice: either she surrender her priestly title or Hall would be forced to resign. She relinquished the office. “Through a moment of deep meditation in which I prayed for God’s guidance,” Li later wrote, “I suddenly saw the light. I realized that I should see my personal prestige as worthless, for I was merely a small servant of the Lord.”

When I first read an excerpt of a letter from Li to Bishop Hall explaining her decision, I cringed. “You are an important man,” she wrote. “I am a mere worm, a tiny little worm.”

That was before I worked at the Farminary, before I knew much about compost, before I learned anything about worms and their superpowers. That was also before I grasped the humility of Li’s act or its particulars: She gave up the office but never renounced her ordination vows. Though the title of priest wasn’t restored to her for nearly 40 years, she faithfully continued her ministry in mainland China.

Li recognized that her vocation didn’t depend on title, office, or recognition. After the Communist revolution in China in 1949, she taught and preached at tremendous cost. Under Mao, she was sentenced to Communist re-education and spent years performing forced labor. During the Cultural Revolution, the authorities confiscated and then burned her Bible. She didn’t dare to make the sign of the cross even in her own personal prayers, for fear that someone might see and report her. But, she said, “the cross was in my mind. Jesus was in my mind.”

Hero.

--

I love the metaphor of the worm.

The worm labors largely in obscurity. While the work of a single worm might be near-imperceptible, in concert with others it is transformative and life-giving. At least according to what science can currently tell us, it has no aspirations to be anything other than what it is. The worm is humble, through and through.

To embrace the posture of the worm is to accept the burden of being overlooked and misunderstood as well as the honor of turning the things of death into fertile soil that can foster flourishing. The worm will never see the full results of its efforts; those will accumulate over the generations. Its labor, its life, comes with inherent risk—beware the hungry robin.

Again and again, I have returned to the garden over the past months and years, digging and weeding and always hoping to glimpse a worm. The worm reminds me to be steady and patient—to remember what is mine to do and to surrender what is not.

I originally wrote three long, petty paragraphs here about folks who got ordained while I’ve waited; about people who tried to nudge me out of the denomination; about loudly public allies who, privately, turned out not to be allies at all. But some things are best left either to the group text or to the compost pile—maybe both.

Remember the worm.

In some ways, I don’t regret the slowness of the process. I’ve lost things along the way: Respect for some people. Illusions about ministry or ministers. Any doubts I had about human depravity. But I’ve gained so much too—and maybe even grown a little.

Remember the worm.

In my denomination, one must receive a call to a particular position to be ordained. Depending on whom you ask, there are strict rules about what’s “ordainable.” Multiple people told me that my role at Crosspointe, where I serve as teacher in residence, wasn’t, because it’s a nondenominational church. Maddening! Also, I’ve always felt that my primary ministry is writing—articles and essays, but also sermons and prayers and, perhaps every decade or so, a book. Though my Classis once ordained someone as a poet, that was in the days when the Church seemed to have a greater imagination.

Finally, the First Presbyterian Church of Berkeley stepped in and called me to be parish associate of storytelling and witness. I’ll lead an online Bible study in June (we’re going to talk about prophets); a couple of times a year, I’ll preach and assist in worship. But mostly, the congregation has committed to supporting what I’m already doing in the world, recognizing it as an atypical yet valuable form of ministry.

So I will serve both at Crosspointe and at First Pres—and beyond. In coming months, I’ll preach to a gathering of Lutherans in Nebraska, at an assembly of mostly mainline folks in Minnesota, and in Presbyterian and Christian Reformed congregations. This cobbled-together, unconventional ministry feels right and good: ecumenical, unconventional, boundary-crossing.

Remember the worm.

--

During a 2001 interview, Toni Morrison was asked how one survives “whole” amidst trial and trauma. “Sometimes you don’t survive whole; you just survive in part,” she replied. “But the grandeur of life is that attempt.... It is about being as fearless as one can and behaving as beautifully as one can in completely impossible circumstances.”

Perhaps one survives in part and then can also find wholeness by growing in new ways. Perhaps. Anyway, I don’t know about behaving as beautifully as one can, but I’m going to try to dress the part.

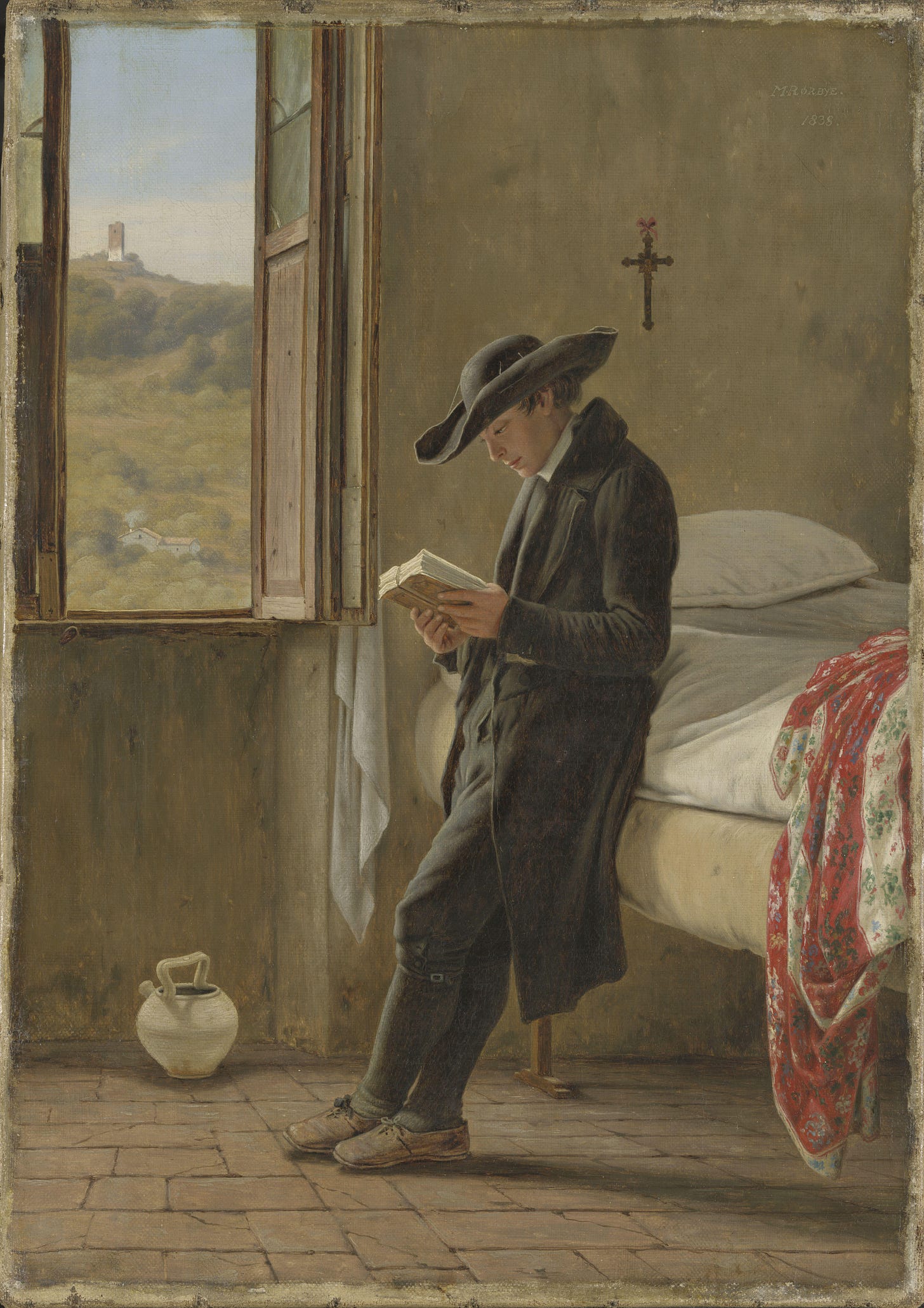

On Saturday, I will wear a clerical robe called the Magdalena. It was made by the Swedish designer Maria Sjödin, who crafts custom robes and shirts for clergy. I contacted her after acknowledging that the off-the-rack options would leave me looking as if I were a kid playing dress-up with a giant duvet, which isn’t good news.

“It’s a dress!” she said when I arrived at her Stockholm studio for my fitting in October. It wasn’t a challenge; it was an observation, an expression of curiosity. “You’re the first man to order the Magdalena. It’s a dress.”

I told her I didn’t mind at all, and I love that my dress/robe/clergy thingy is called the Magdalena. Mary of Magdala, after all, is a disciple who has been misunderstood and misrepresented. Her faithful example is plainly there, if only one would like to perceive it: healed and restored, generous and sacrificial, bearing witness both to the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ.

It actually wasn’t until the sixth century that Mary’s biography was embellished with allegations of prostitution. What would she make of the added flourishes? I like to think that she’d be unbothered, though she was only human. Anyway, I hope that, each time I put the Magdalena on, I’ll remember the ways in which I’ve been healed, recall what God has done for me, and care well for all the people whom the Church has treated as less-than. I hope that I’ll be able to embody some good news.

As Bonhoeffer said, “Sometimes I simply cannot see how I will be able to do all these things right.” I might word it a bit differently: I know I cannot get all these things right. I will disappoint people. I will make mistakes. I will use the wrong word and say the wrong thing. But, as I will promise on Saturday, I’ll do my best “to faithfully discharge my office... and adorn it with a godly life.”

I hope that will be enough.

All are welcome at the ordination, whether you wish to join us online (here’s the link to the livestream) or in the sanctuary (729 Carroll Street, corner of 7th Avenue, in Park Slope). 11 a.m. Eastern time, Saturday, April 6th. If you’re joining online, you might wish to prepare some communion elements; you can also access the bulletin here.

Pray for me.

Yours,

Jeff

It already is enough. God has called you AND equipped you for Her Service. And as Eugene Peterson says, ‘A Long Obedience in the Same Direction’. This is who you have been and who you are now.

Alleluia!

Thank you so much for giving a glimpse into your thoughts as you lead up to the big day! I appreciate your perspective on things so much— your meditation on worms actually brought me to tears, as I have been struggling this week with feeling like nothing any of us do matters. It gives me encouragement to keep "making compost" where I'm at.

I hope the ordination goes well!