We Still Have Hope

Some fragmented thoughts on Christmas Eve, family gatherings, gift-giving traditions, and Japanese milk bread

The 204th Day after Coronatide*

Christmas Eve

Dear reader,

Confession: I’ve always loved Christmas Eve more than Christmas itself.

When I was a kid, we’d go to a candlelight Christmas Eve service at church. Sometimes I found the sermon boring or felt sleepy in the dim sanctuary. But I’d perk up as soon as I reminded myself that, as soon as “Silent Night” started, we’d get to light our candles and I’d get to play with the melting wax. The challenge was to craft little stalactites without letting the hot liquid drip on the fabric of the padded pew. (My mom would gently slap me if she saw that happen.)

When we got home, the house would be quiet. The Christmas tree’s twinkling lights shone on the neatly wrapped boxes beneath. Our household tradition was that we each got to open one present on Christmas Eve. I liked this practice. For one thing, it felt like low stakes. Weirdo that I am, I’ve always been a fan of tempered celebration—nothing too ostentatious, nothing too loud. I also appreciated that if I didn’t like whatever I opened that night, there would always be other packages to open the next morning. I still had hope.

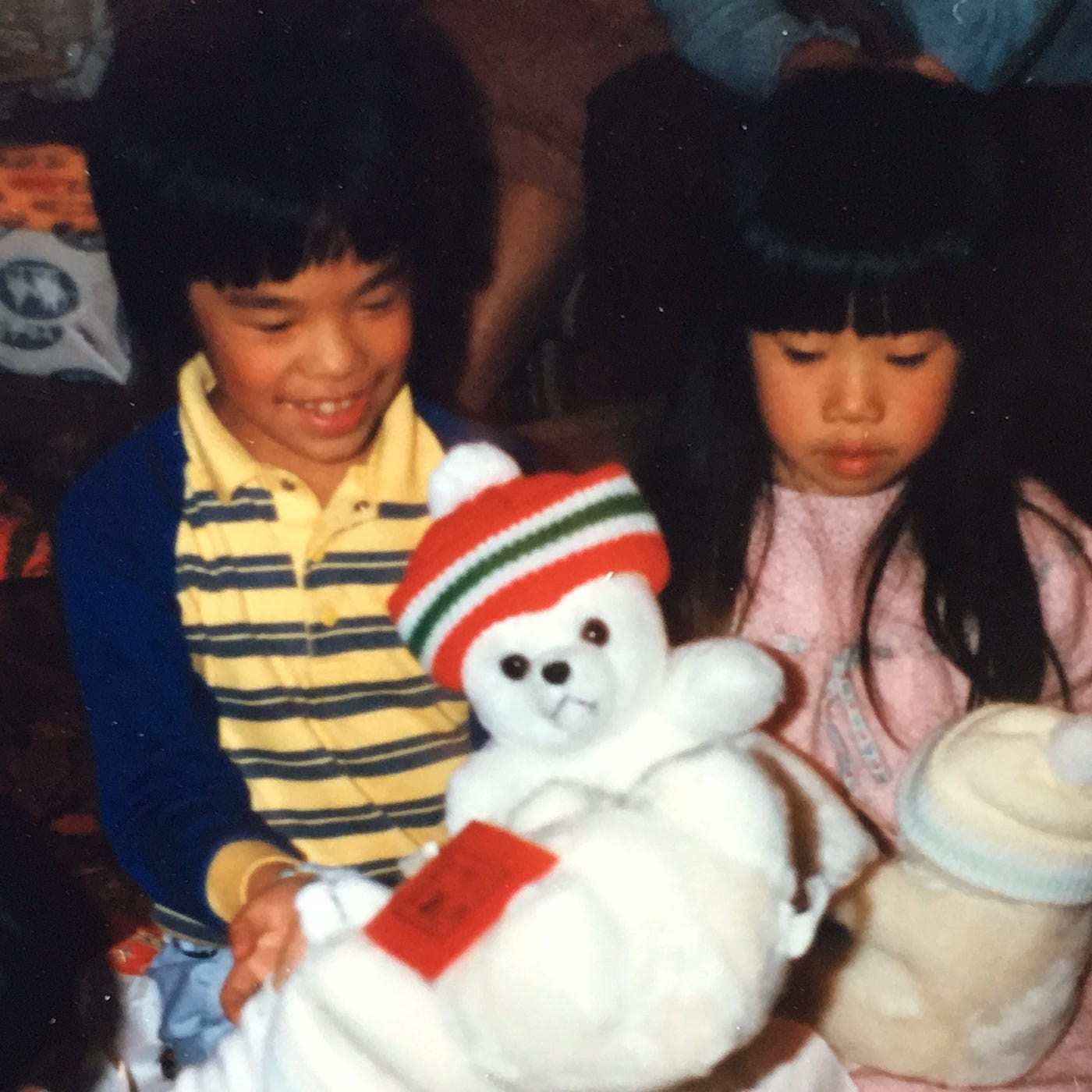

We deployed our own strategies. My sister would typically open the biggest package first. My mother would choose a small one. I usually tried to pick something that, following my careful analysis of the options, I thought I already had identified—or else a book, because I’d always like that. My mom, dad, and I all learned not to open anything from my sister, because at an early age, she developed a habit, which she found hilarious, of stealing things we already owned, wrapping them up, and “giving” them back to us.

Christmas Day was always about big family gatherings, usually with my dad’s side of the family. When Chinese families gather, the noise level rises completely out of proportion to the number of people. Conversational Cantonese isn’t a particularly elegant language anyway; even when they’re not yelling at you, my people can sound as if they are. A couple of members of my extended family are extremely hot-tempered, which I found difficult to endure. So I’d typically park myself in a corner of the kitchen with a book or a stack of blank paper and a pen, and I’d read or draw the day away, keeping one ear attentive to the women trading stories and news as they cooked.

Once we had endured the interminable Baptist pre-dinner prayer—come, Lord Jesus, and soon—we got to eat. The food was reliably good. One of my aunts makes famously wonderful soup, rich with pork and chicken, and a big pot was always simmering on the stove. My favorite: the generous piles of barbecued pork and roast pork and soy-sauce chicken and especially roast duck, the crispy skin lacquered and glistening. I could make a happy meal out of just those animals and a big scoop of white rice.

The major problem began after dinner, when we went around the room, opening presents one at a time.

My people don’t open gifts in front of the giver. You’re supposed to show gratitude for the idea of the gift, regardless of what the package contains, and the discipline of not peeking is immensely helpful. If that red envelope holds a five-dollar bill, not a twenty or a hundred, the giver is spared the sight of the greedy kid’s face falling in covetous disappointment. If the shirt comes in the wrong size, the wrong style, or the wrong everything, you can be rude and ungrateful in the privacy of your own home.

On Christmas, though, we turned out backs on the traditional Chinese protocols. This was a grave mistake. I’ve always been a terrible liar; my face gives everything away, which adds a layer of meaning to the Chinese concept of “saving face.” I don’t recall, because I refuse to recall, how many Christmases resulted in some humiliating moment of involuntary disclosure, my face declining to cooperate with my mouth’s attempts to express gratitude. I don’t recall, because I refuse to recall, how many Christmases compelled my mother to loudly, publicly Jesus juke me, reminding me that our Lord and Savior was the best Christmas gift of all.

If you were thinking that I was waxing nostalgic about those big family gatherings because this is a year when we can’t do that, well, you’d be wrong. I do not miss them! I do not miss doing Christmas that way! The first Christmas I celebrated with my husband’s mercifully smaller family was a revelation. Yes, they open some gifts together, but with a key difference: Gin (or wine or your drink of choice) is available. I do miss the roast duck and my aunt’s soup, though.

These days, I still love Christmas Eve best. It feels worthy of more attention than we often give it. I love its quiet. I love its hope. I love its lack of forced merriment. I love its preparatory focus. I love its realism—its steadfast refusal to turn away from our need for help alongside its unwavering confidence in the embodied salvation that will come. I love its liminality, which feels true to so much of the rest of life.

In this year of so much waiting, Christmas Eve feels pregnant with both anxiety and possibility. The anxiety of travelers searching for safe haven. The possibility of a family on the cusp of new life. The anxiety of humans confronting the unknown. The possibility of the faithful hoping for the fulfillment of grand promises. The anxiety of the exhausted just in need of some small mercy. And still, the possibility of some unexpected in-breaking of grace.

What I’m Cooking: I didn’t grow up in a household of bakers. In Hong Kong, my mother and grandmothers did not have ovens. So the learning curve has often felt steeper for my mom and me when it comes to making breads, pies, pastries, and cookies. I’ve gotten pretty good at making pie crust, but in recent weeks, I’ve marveled at my friends who churn out batch after batch of various kinds of Christmas cookie. I couldn’t muster the courage.

Baking has sometimes seemed futile, too, because I grew up on the airy, light, chemically enhanced baked goods of Hong Kong-style bakeries, cakes and pastries and breads made for a palate that prefers things not quite as sweet. But I’d read that shokupan—Japanese milk bread—delivered the kind of soft-textured crumb that I knew from the raisin-flecked loaves and cream-filled rolls of my childhood. Last week, I finally tried it, using a recipe from the New York Times.

The key technique is the use of a water roux (the Chinese version is called tangzhong, the Japanese known as yudane). The Times recipe, which uses the tangzhong method, calls for a roux made from flour, milk, and water. Don’t let me fool you into thinking I know more than I know. Tangzhong, as the bread geeks over at King Arthur Flour explain, “pre-gelatinizes the starches in the flour, meaning they can absorb more water... Not only does the starch in the flour absorb more liquid; since heating the starch with water creates structure, it’s able to hold onto that extra liquid throughout the kneading, baking, and cooling processes.”

It was so easy to make! My shokupan was a lovely loaf with a fine crumb and a pillowy texture. The flavor was not the most interesting; it was a respectable, versatile white bread. Toasted and slathered with salted butter and jam, it tasted good, because it was a willing vehicle for salted butter and jam. It was a decent sandwich bread. It made outstanding French toast. Also, the bread looked like a butt.

Some notes: I halved the sugar in the recipe; though we don’t like things very sweet, I might add a bit of that back. Also, my tangzhong cooked much, much faster than the recipe suggested it would.

What I’m Growing: One of my projects during my Christmas break will be to spend some quality time with seed catalogs, imagining what I might like to plant next season. I’d love to know what you love to grow, especially if you think it might work well in these Upper Midwest climes.

What I’m Reading: In her newsletter, “Field Notes,” my friend Sarah Bessey, who rivals me in unabashed earnestness, posted a lovely Christmas prayer for the broken-hearted the other day. If you’re into that kind of thing, the whole piece is worth a read, but as a hope junkie, I especially love this line: “I pray for hope to rise, unbidden and unforced and surprising, like a flower breaking through the cement in a parking lot. I pray for you to tend that tendril of hope like a gardener, protect it, let it grow wild and unexpected into the places you least anticipated.”

I’ll be off social media for the Christmas holidays, and I’m determined to spend a little more time reading ink on paper, not pixels on screens. Two books on my stack: Norman Wirzba’s Food and Faith: A Theology of Eating—I’m curious to understand why we have so many theologies of eating, theologies of consuming, and so few about cooking and preparing—and Yaa Gyasi’s Transcendent Kingdom, which my book group at church will be discussing in January. What’s on your reading pile?

This will be no ordinary Christmas for any of us. I suppose every Christmas is inflected with both joy and sorrow, happiness and pain. Isn’t that the reality of life this side of heaven? Even so, this year feels different.

Whatever it might look like for you and yours this year, my hope and my prayer is that love will melt your worries, that joy will surprise you, and that peace will, even for just an unexpected moment here or there, disrupt your day in the most beautiful way. Christmas blessings from our house to yours, even from Fozzie, who refuses to look at the camera.

I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Yours,

Jeff

*I’m still counting my days from June 1, when my governor, Gretchen Whitmer, lifted Michigan’s stay-at-home order. Michigan’s numbers are, thank God, significantly down from a couple of weeks ago. Vaccine distribution continues. Let’s please continue to wear our masks and stay safe.