A Gracious Reception

Some fragmented thoughts on how we read, essays, empathy, tortillas, zinnias, the late-summer garden, and the discipline of joy

Thursday, September 7

Grand Rapids, Mich.

A wondering this week, about reading.

As I’ve been working on Good Soil, which is a memoir, I’ve been wrestling with how we read. In other words, how do we receive others’ stories, especially those that differ significantly from our own? What do we look for, and how do we respond?

I’ve been wrestling with how we read because those of us who publish—whether it’s a social-media post, an essay, a sermon that’s preached, a song that’s sung, a book that you hold in your hands—write to be read (or to be heard). And part of the faith built into this act of publishing—indeed, part of the fear—is that, once it’s out in the world, we have little to no control over how our stories are received.

In third grade, I published my first book. It had an extremely limited print run: There was just one copy.

The book was about my stuffed bear, who is named Bear and who is still with me, sitting on the middle shelf of my bookcase, watching me as I write. My teacher, Carmen Gonzalez, had each of her students workshop a story, print out the text, illustrate each page, and even bind the book by hand—a gentle lesson in the loving, multifaceted labor that can go into storytelling.

When I was workshopping the story, I remember several of my classmates not hearing much that I had to say beyond the introduction of my main character: Why would Jeff call his bear Bear? That seems really boring and not creative.

I called my bear Bear because that was what I wanted to call him, because that was always the name that he’d had, as long as I could remember.

But I would never have named my bear Bear.

But it’s not your story, is it?

My hope then, although I didn’t know how to articulate it, because I was eight, was for a more empathetic reader. Sure, I could have told the story better—I was eight!—but I wonder why they got stuck on Bear’s name and why they couldn’t get past the fact that they would never have been so utterly uncreative.

But it was not their story.

In recent years, even in recent weeks and days, a few essays have gone viral in particular circles. The pattern has become familiar: The essay goes up; some readers find points of resonance, which is why they share it; then others encounter it and are irritated, pointing out all the problems with the essay. Sometimes I’m not sure whether it’s the essay itself or the subsequent virality that others find irksome. But among the common responses are statements along the lines of “But that hasn’t been my experience,” and “But he didn’t name this thing that I have felt,” and “But I wrote something about this and it didn’t get this kind of attention,” and “But I’ve suffered more and he should check his privilege.”

Those “buts” could easily, and more charitably, be “ands.” The truth of another’s experience doesn’t diminish the reality of mine or yours. What in our world has trained our fast-twitch muscles to react by saying, “I don’t see that,” rather than, “I’m so sorry they experienced that”?

To be a more empathetic reader is to acknowledge that an essay is, as its very name suggests, a try—the root word is the French essayer, “to attempt.” Even when I’m hate-reading, say, the weekly “Modern Love” column in The New York Times, which I find irritating more often than not, I remember the brave futility and the beautiful folly of trying to compress a complicated human experience into 800 words and then putting it out into the world for us vultures to pick at.

To be a more empathetic reader is to recognize, too, that, as a reader, I am not the protagonist of the story. Not every story is about me and not every story is for me. Not every story is about you and not every story is for you.

Part of the beauty of reading—and, maybe, part of the work of reading—is to experience another human’s world, another person’s perspective. Of course, you have the freedom to disagree, to find that perspective likable or loathsome, to skitter on back to your own world as quickly as you wish, or even to write your own essay. I wish, though, that the primary question when we encounter another’s work were not, “Where do I find myself in this?” but, “How has the writer found themselves here?”

Perhaps that posture is most difficult to maintain is when the cultural markers and social location of the writer are closer to one’s own; comparison is so easy, so tempting! Take me far beyond my usual context, and it can be easier to find a little charity and to allow the writer more latitude.

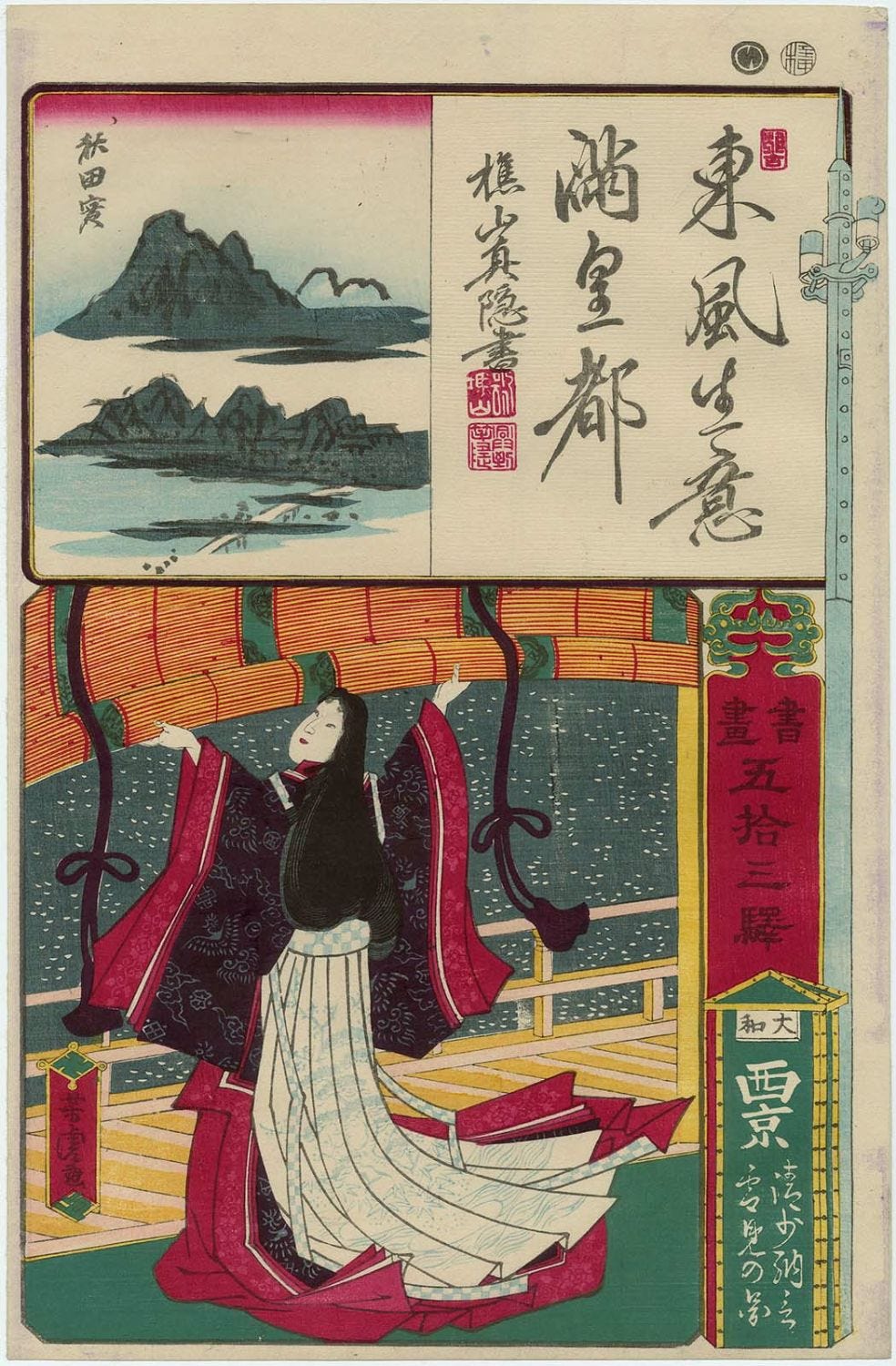

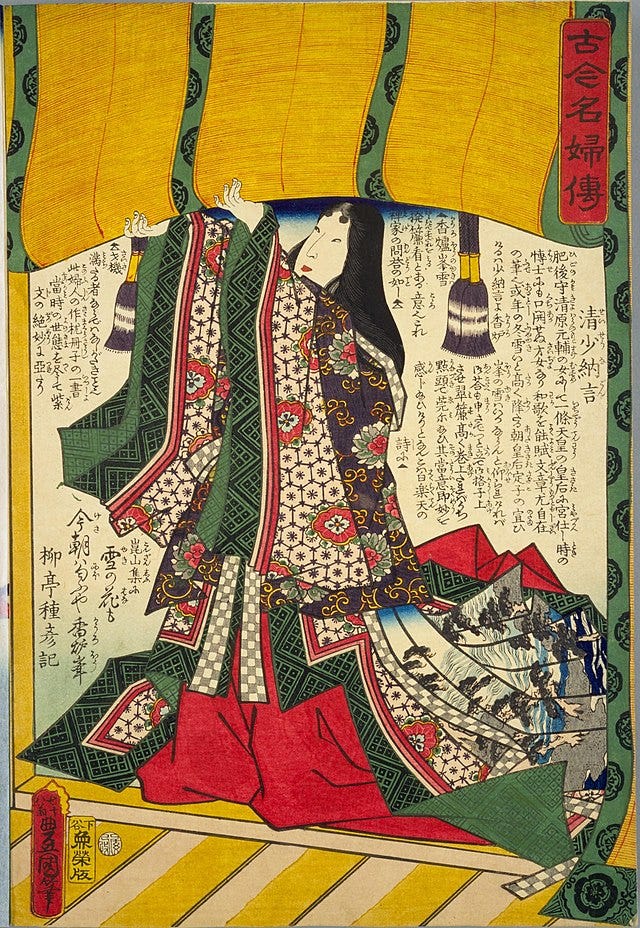

One of history’s first known essayists was Sei Shonagon, a Japanese imperial courtier who wrote in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. The daughter and granddaughter of poets, she authored The Pillow Book, a wide-ranging, genre-bending collection of musings on everything from late-night dalliances to court gossip to her evaluations of various birds. (You can read the full text of The Pillow Book online here.)

Sei Shonagon is wild! For instance, she has an essay entitled “A Preacher Ought to Be Good-Looking.” “We must keep our eyes on him while he speaks; should we look away, we may forget to listen,” she writes. “Accordingly an ugly preacher may well be the source of sin.” No comment!

One of my favorite selections from The Pillow Book is called “Depressing Things.” It’s an essay distilled into the basic form of a list: “A lying-in room when the baby has died. A cold, empty brazier. An ox-driver who hates his oxen.” She veers in all kinds of directions: “It is quite late at night and a woman has been expecting a visitor. Hearing finally a stealthy tapping, she sends her maid to open the gate and lies waiting excitedly. But the name announced by the maid is that of someone with whom she has absolutely no connection. Of all the depressing things this is by far the worst.”

To read Sei Shonagon is to be whisked to another era and place, a world of rigid formality, strict rules and regulations, and remarkable behind-the-rice-paper-screens shenanigans. And part of the pleasure in reading her is to have her slide back the shoji, giving us access to a world that is in some ways so foreign that the moments of remarkable relatability surprise us. With time and distance, perhaps it’s easier for us to empathize without saying, “But I wouldn’t have told the story that way.”

Maybe more points of connection make it harder to read empathetically.

For those of us in the Christian tradition, Paul is often regarded as one of the most difficult but most influential writers of Scripture. People love to hate Paul. For ages, I did too. He’s often regarded as something of a pompous jerk, maybe because he can be a pompous jerk. But even as he is being a pompous jerk—exhibit A: his gratuitous swipe at vegetarians, whom he describes as “weak” in his letter to the Romans—he is also kind of funny and gloriously, humanly petty. Anyway, I was not one of the original recipients of his letter; it’s called the letter to the Romans for a reason, and I’m reading someone else’s very old mail (something, I confess, I have always enjoyed).

Paul can be especially frustrating if one reads his words and constantly asks, “What is he saying about me?” That’s not to minimize the theological importance or the spiritual wisdom in his writings. By no means! But Paul becomes a far more sympathetic character when I wonder, “What is he saying about himself, and his dreams, and his yearnings?” I’ve slowly been training myself to ask as I read Paul: How did this human end up writing these letters? What in his experience compelled him to say what he said? What joys and what sorrows sit behind these words? What hope and what pain move this writer’s heart?

Somewhere out there, a reader has been building toward a “Yes, but...”: Yes, but isn’t it the writer’s responsibility to address all possible critiques? Yes, but isn’t the writer’s job to be a better, clearer communicator? Yes, but shouldn’t the writer have accounted for x, y, and z?

Maybe! And that’s not what I’m writing about today.

To be a more empathetic reader is to reject the lie that there isn’t room enough in this world for all our stories. It is to rebuke the noxious ranking of lived experience. It is to embrace a generosity that makes room for imperfect storytelling—and imperfect storytellers. It is to acknowledge that, yes, there are stories that are untold as well as stories that are offered but listened to less than others—and also to receive in a spirit of curiosity the ones that are told. It is to accept an invitation into the wideness and the mercy of the “Yes, and....”

To be a more empathetic reader is to give a gift that I wish we would offer to more writers. I say “gift” because it’s not mandatory; it has to be voluntary. You might also call it “grace.”

What I’m Cooking: We all have foods that speak to our spirits and sing to our souls. Often, we ate these dishes in our youth, and they still spark delight. For Tristan, a good tortilla is, I think, one of those foods. I recently bought him a tortilla press and some heirloom-corn masa, and on Tuesday evening, we had homemade tortillas for the first time, which we used to make steak tacos with leftover meat from the night before. I give our first attempt a solid B+! (We don’t do grade inflation in our household. B+ is a good grade.)

The next morning, we had a few leftover tortillas, so I made migas. I love dishes that tell a tale of resurrection. In Spain, migas is traditionally made with stale bread, and in Mexico, it often repurposes old tortillas.

Because Tristan is from Texas, our version hewed more to the Tex-Mex style. I sliced the tortillas into thin strips, then fried them until crisp, in a little oil, in a hot cast-iron pan. I chopped up a banana pepper, a tomato, and a bit of onion, and tossed all that in. Finally, I added three beaten eggs. We topped the migas with salsa verde that I made the other day from our abundant volunteer tomatillos. A satisfying breakfast!

What easy home-cooked dishes give you comfort and nourish your soul?

What I’m Growing: The zinnias are still going strong, sending up bloom after varied bloom, in so many different patterns and colors. I cut a few yesterday to put by my desk—a constant reminder as I write, I hope, of the surprising beauty and gracious love that I want to be at the heart of my book.

Our bean crop has not been quite as robust as last year’s, thanks to the dastardly Mexican bean beetles. But still, every single one of the beans that we do have is a miniature work of art.

In the garden, the rest of the beans are slowly drying out, and the sunflowers have mostly faded. Yet even as they droop, they have their own beguiling elegance. When I see one, I think of all who have fed on its goodness—and are still feeding, as it turns out! And even as these blossoms fade, they’re setting seed and preparing for new life.

Where are you being surprised by beauty and encountering unexpected goodness?

In her vital new book, Sacred Self-Care, the Rev. Dr. Chanequa Walker-Barnes, who also writes the very good Substack newsletter “No Trifling Matter,” discusses the importance of making room in our lives for joy: “Our days are so full of activity and busyness that we do not take time to revel in the bounty of our lives: the beauty of nature, the laughter of children, the warmth of sunshine, the delight of a snowflake on the tongue, the pleasure of dancing with wild abandon.”

I love how most of the examples she names aren’t things that we earn or even do. They’re simply there to be noticed and received. Joy, she adds, “is a discipline, something that we should seek and cultivate as an act of vulnerability and gratitude.” I’m still not much good at it, especially that dancing with wild abandon part, unless we’re talking about dancing inside one’s heart. But one can dream! One can try.

May you tend your joy this week—and may it also surprise you like a volunteer flower in the garden.

I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

In hope and with gratitude,

Jeff

lol yes to "But it’s not your story, is it?" It's so maddening, especially on social media when we have to give a thousand disclaimers. I do find that it's one symptom of a larger issue at the intersection of consumerism and Christian culture that every form of media is design to preach at us or sell us on something. It's right in the name of "evangelical media," but that style influences too heavily into personal posts and videos, so we're trained to constantly be preached at as well as marketed to. Even if you don't have a specific product to earn money from, it's in the way we (often are required to for certain careers) build our "brand." Phrased in the imperative, to a hungry audience who wants to be told what to do and think and say to not offend and make life easier, even if it's veiled politely as an ad testimonial to why it works.

So when as contemplative or narrative or memoir writers, we say, "This is my perspective," an audience of consumers with marketing-fed preached-at brains replies (or quote tweets), "But what about me? I thought writing, publishing, and posting were teaching/preaching/influencing/meeting MY needs and desires? I can't buy this and instantly have a better, more magical life?" I think we'd all do well to take into consideration the contemplate principle of "use I language to speak your truth" and then "listen with a posture of openness and mindfulness" in return. This isn't a "we all" or an implied "you" in an instruction or a sermon or advertisement; just my own story to tell, and I am open and grateful to hold your own in response. Not when phrased as a criticism, but when phrased as a conversation. I do want dialogue. I don't need unsolicited critique. And the more we deconstruct from the evangelical capitalism machine, maybe we can reclaim that as a society?

this.

" reject the lie that there isn’t room enough in this world for all our stories. "

❤