An Investment in Hope

Some fragmented thoughts on interdependence, my participation in the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine trial, tofu stir-fry, and pretty pictures

The 239th Day after Coronatide*

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Dear reader,

Last week, the United States passed a grim milestone: 400,000 Americans dead from COVID-19. Nearly 100,000 have died in just the past month. The numbers are so big that they are nearly incomprehensible. The nation has grown numb to the daily reports and ever-climbing tallies, and we haven’t begun to reckon with the reality behind the numbers: the loss of so much heritage and so many stories, so much wisdom and so many meals and hugs not shared.

Every day, Tristan and I walk Fozzie up and down the streets of a city we have come to love. Grand Rapids has 200,000 people. What if Grand Rapids were totally obliterated twice over, in a matter of months? That’s exactly what has happened—yet here we are.

I’ve been frustrated at how many of our fellow citizens have thrown up their hands—“what can we do?”—and/or issued their own personal declarations of independence, explicitly proclaiming that they will not change their lives, that they “will not give into fear,” or implicitly doing the same by keeping life as normal as possible, Instagrammable vacations and all. We’re seeing the toxic blossoms of deeply rooted American individualism. In some seasons, that characteristic seems hardy and robust; in times like these, which demand collective sacrifice, it can be deadly.

At times during this pandemic, I’ve been afraid: afraid that we’re not taking enough precautions; afraid that my loved ones might suffer or even die (two close family members have tested positive for COVID-19); afraid of the havoc that this virus, which we’re still struggling to understand, can wreak on a body, on a mind, on the fabric of a society. If perfect love casts out fear, it’s not hard to understand why fear is rampaging through this country. We have not loved one another well.

Every day is a new invitation into repentance, though. And there’s so much we can do, so many ways in which we can foster interdependence: wearing masks; keeping safe distance; exerting healthy peer pressure; listening better, especially to the most vulnerable; confessing and addressing our addictions to comfort and convenience.

A few months ago, we had a frank conversation in our household, after I read that Johnson & Johnson was recruiting volunteers for its vaccine trial, called the Ensemble study. We’re not early adopters of anything; my parents bought me my first iPhone, because they thought it was sad that I still had an old, hand-me-down BlackBerry when so much of the world had progressed. Yet this felt different. I’m relatively healthy. The researchers need a diverse pool of participants; though they’re running the study in eight countries, none are in Asia. The J&J vaccine had already been found safe in its initial trials, and the method has been used before. Plus, we figured that if something went terribly wrong, well, at least we don’t have kids. So I registered, joining about 45,000 other people all around the world. It seemed like a small thing that I could do to invest in us.

This vaccine uses different technology than the Pfizer and Moderna ones. It’s built on a method developed at Harvard Medical School, grafting genetic material from the coronavirus onto a deactivated common-cold virus. Injecting this modified virus into the body sparks a chain reaction: human cells produce a protein found on the COVID-19 virus, which then prompts the immune system to make antibodies that can fight off that virus. The vaccine also doesn’t need to be kept in deep freeze, so it will be easier to deliver to some of the places that need it most. And it’s just one dose, not two, making it much more accessible on another level.

In early December, I headed to Cherry Health, a community-health center here in Grand Rapids, for a six-hour introductory session (we were told to bring a bag lunch, and I was that jerk who packed a tuna-fish sandwich, which I ate, with a side dish of guilt, as the smell filled the room). The research team walked each small group of potential volunteers through a long document about the potential risks as well as the science behind the study. They answered all our questions; when one person in my cohort expressed fears that the vaccine would give her COVID. The staff patiently explained that this couldn’t happen, that it wasn’t that kind of vaccine, that it didn’t contain a weakened COVID-19 virus.

We each met one-on-one with two doctors, who answered any lingering questions and talked us through a long medical questionnaire. A research assistant took our height and weight; another took our temperatures and measured our oxygen levels. Over and over, we were reminded that some participants would receive the experimental vaccine and the rest would be given a salt-water placebo. We were told that the study is scheduled to last for two years, but over and over, we were also reminded that we could exit at any time. Finally, those of us who still were willing to participate signed our papers and we lined up to get our shots.

A couple of weeks ago, I emailed Dr. Leslie Pelkey, the chief medical officer of Cherry Health and the lead investigator on the Grand Rapids part of the global J&J trial, because I had some questions. For decades, Cherry Health has provided medical care without regard for a patient’s ability to pay for it. The majority of its patients are people of color, and we know that communities of color have been disproportionately hit by COVID-19.

For the past 13 years, Cherry Health has had a research operation, because it believes that its clients deserve to be part of the process of building the future. I asked Pelkey why she wanted to be a part of this particular study. She shared about the experience of treating COVID-19 patients. Many recovered quickly, but others spent weeks in the hospital. “Their stories of suffocation and fear and loneliness are heartbreaking,” she said. Not all survived. “One of my patients lost his life, despite all of his heroic efforts in concert with the specialists caring for him,” she said. “The picture of him holding his wife’s hand in the end was shared and will stay with me forever.”

Then there’s the doctor’s calling, coupled with the reality of being human. “As a physician, I am called to heal,” Pelkey said. “But with this new disease, there is no curative prescription to write, leaving a sense of helplessness.” She realized that this study could help change the equation. “To be able to participate in the Ensemble trial has given me hope,” she said. “Hope that I can soon safely see my friends and family, who I miss dearly.”

I share that hope. I don’t know if I got the vaccine or the placebo. My arm felt a little tender afterward, just like it does after any other shot. For a couple of days afterward, I felt nauseated—but was that just my brain playing tricks on me, generating a response because I really, really wanted one?

I think about that hope every Monday and Thursday, when, as instructed, I take my temperature and check my oxygen levels and then report, via an app on my phone, whether I’ve had any symptoms that could indicate COVID-19 infection.

I thought about that hope in early January, when I went back to Cherry Health for my first follow-up visit. They took my temperature, drew some blood, asked me some other questions, and then sent me on my way. I’ll be back in February for another check-up; there are a few more after that.

We should learn next week whether Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine candidate is working. Of course I’m afraid—afraid that it won’t work as well as it did in the early trials; afraid that the virus will mutate faster than science can handle; afraid that we’ll continue to live under the specter of a microbe that has such awful power; afraid that we’ll fail once again to learn necessary lessons about interdependence.

It helps to be reminded of all the texture of the word “fear,” especially for those of us who spend time in Scripture. In his book God in Search of Man, the rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel explains that the Hebrew word yirah can indeed mean fear of danger or calamity. Even this kind of fear can be good—it’s a human survival instinct—and it can be bad, if it’s irrational, say, or based on prejudice. But yirah can also mean “awe”—the kind of awe that one should have when regarding the miracle of a newborn child or the swirls of the Milky Way against the midnight sky or the impossible magnitude of God’s grace. “Fear is the anticipation and expectation of evil or pain, as contrasted with hope, which is the expectation of good,” Heschel writes. “Awe, unlike fear, does not make us shrink from the awe-inspiring object, but, on the contrary, draws us near to it. That is why awe is compatible with both love and joy.”

Yes, I’m afraid. Yet on my better days—or, to be honest, in my better moments—my good yirah wins out over my bad, and my awe—at God, at the gift of science, at the transcendent beauty of communities coming together for the sake of one another—prevails over my fear. In partnership with love and joy, awe feeds my hope, and that is, I think, as it should be. How else can we make it through?

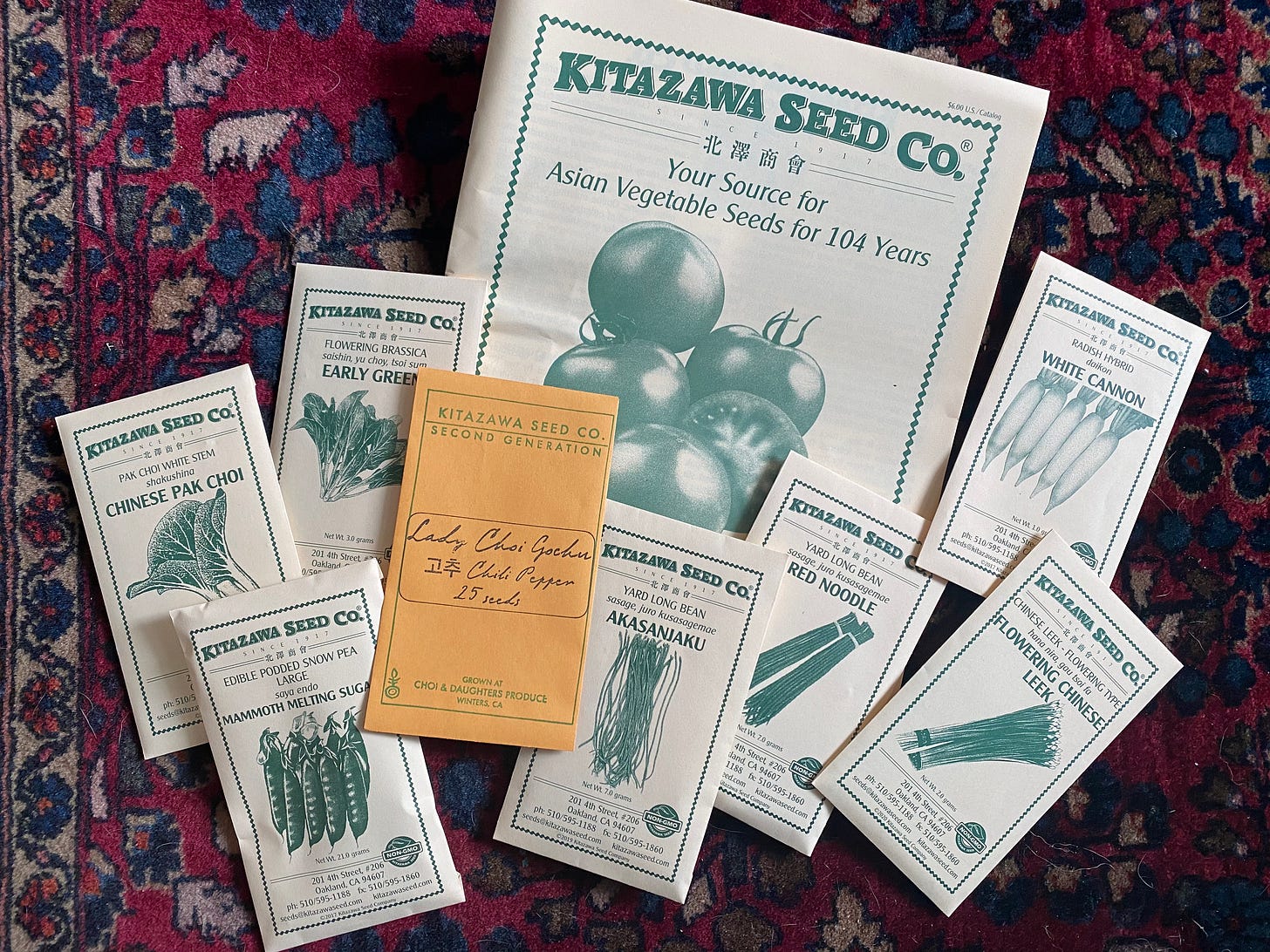

What I’m Growing: Seeds for the new season have started to come in! This week, I got my shipment from Kitazawa Seed, a 104-year-old California company that has a fascinating history of survival through the Japanese internment. Kitazawa is where I go for most of my Asian greens; even though my choy sum didn’t do well last summer—I’m wondering if it needs more subtropical heat and humidity—I’m trying again.

What I’m Cooking: Two staples I keep in my fridge: gochujang, the beautifully spicy Korean chili paste, and oyster sauce. Last night, we wanted a simple vegetarian dinner, so I pan-seared some slices of tofu; chopped up some shiitake mushrooms, an onion, a couple scallions, and some chard; and stir-fried it all together with a big spoonful of gochujang, a couple of glugs of oyster sauce, a splash of vegetable stock, and salt and pepper. It was quick, it used only one pan (Tristan teases me about how “a simple dinner” can mean multiple pots and pans), and it was great over brown rice. If you’re not into tofu, well, I wish you’d try my tofu, but this works with chicken or pork too.

What I’m Reading: Since 2014, the photojournalist Marzena Skubatz has been visiting a remote weather station on Iceland’s eastern flank. I came across Skubatz’s words and images via the New York Times, which, throughout the pandemic, has been transporting readers all over the globe through a photojournalistic series called The World Through a Lens. The headline struck me: “Monitoring the Weather at the Edge of the World.” What’s at the center, if that spot in Iceland is at the edge? How do we define centrality anyway?

What I’m Watching: What I wouldn’t give for a chance to hike the Yorkshire Dales right now. Someday. But the next best thing: All Creatures Great & Small, a new Masterpiece/PBS adaptation of the classic James Herriot books, which I adored when I was a kid. The Scottish actor Nicholas Ralph plays Herriot, a veterinarian who gets his first job tending to the calves, cats, and egos of the English countryside. The show is gentle and gorgeous, the televised equivalent of the coziest afghan.

My last Sunday at Central Reformed Church will be this Sunday, January 31. I started at the church on January 15, 2020, which seems like such an innocent time. We could still travel! We could still gather in person! We could still sing in church!

Originally, my gig as teacher-in-residence at Central was for one year. Because of COVID, the church extended that for a couple of weeks—just enough to finish up a Bible study and a book group as well as for me to preach one last time. I hope you’ll join us online for worship; music begins at 9:20 a.m. ET, the service at 9:30. I’ll be preaching on Psalm 111 and Mark 1:21-28—yeah, the kid who grew up Baptist got a demon passage for his last sermon.

I’m so grateful to this congregation for their trust and for this opportunity to journey together. Also, Tristan, Fozzie, and I plan to stay in Grand Rapids for now. We’ve come to like it here. I’ll focus on pretending to write and on trying not to kill plants.

As always, I love to hear from you. Tell me how I can be praying for you.

And as always, I’m so grateful we can stumble through all this together. I’ll try to write again soon.

Yours,

Jeff

*I’m still counting my days from June 1, when my governor, Gretchen Whitmer, lifted Michigan’s stay-at-home order. Right now, we have one of the lowest COVID-19 rates in the country, which honestly isn’t saying a lot. Please stay safe, wear your masks, and stay home as much as possible. We can do this.

I need prayer for my marriage.

Wonderful message today.