Gentle Strength

Some fragmented thoughts on being like water, Lao Tzu's timeless wisdom, a cherry tree, and grievous division in the church

Friday, June 16

Grand Rapids, Mich.

Hopes raised, hearts shattered: This feels like the story that we live again and again, individually and communally. It isn’t even sequential: This week, my hopes rose in one part of my life, and my heart shattered in another.

How do we keep doing this? What empowers us to keep going? When do we get a break? Do we have any other choice?

As I stewed in a vat of mixed emotions, three words came to mind: Be like water.

You might be thinking: OMG, he’s quoting Bruce Lee?!?! And if that were the case, I would be as surprised as you are. Yes, the kung-fu master tucked that line into one episode of a 1971 TV show. But the wisdom was not his, nor were the words. They were written down late in the 6th century BC or perhaps early in the 5th, by the ancient teacher Lao Tzu.

“Best to be like water, which benefits the ten thousand things and does not contend,” he wrote. “It pools where humans disdain to dwell.”

Be like water.

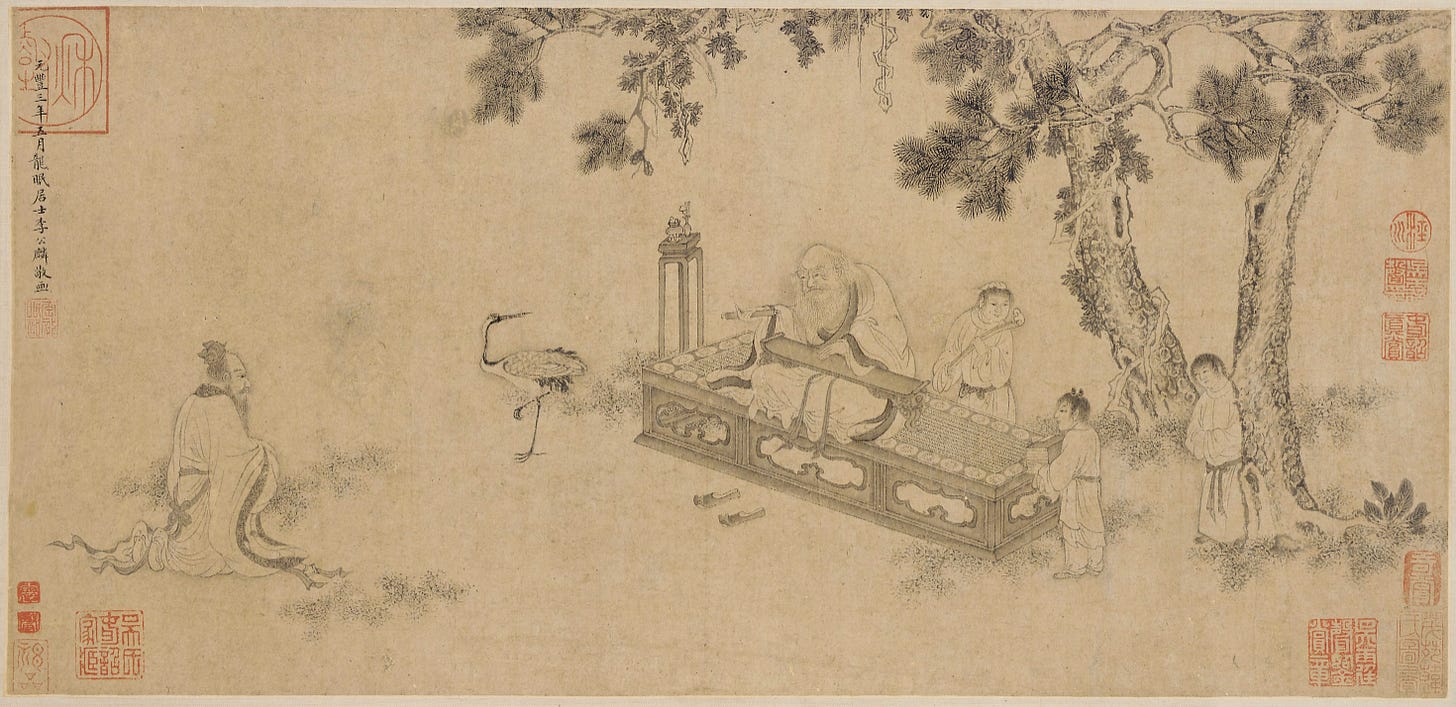

Lao Tzu wasn’t his real name; it was an honorific. 老子 can be translated bluntly “Old One.” But given the traditional Chinese respect for the aged and their wisdom, it’s perhaps better and more elegantly rendered “Venerable Master.”

It’s believed that he was born Li Er. The son of a courtier, he rose to become archivist of the royal court of Zhou. He tended to the collections of oracle bones and bamboo fragments, studying and marshaling history and philosophy for the benefit of the king. Even in his lifetime, Lao Tzu’s renown was sufficient that, according to some sources, Confucius traveled to seek his counsel and wisdom in person. Legend tells us, though, that he put little stock in his own fame. After retiring from his government job, he reportedly moved to the countryside and became a hermit.

The lines including the advice to be like water come from the Tao Te Ching, a text comprising 81 short sections—epigrams and provocations, poetic snippets and paradoxical mind puzzles. As with the Bible, we lack insight into the original shape and form of the Tao Te Ching. The oldest extant fragments, etched on shards of bamboo, come from at least a couple of hundred years after Lao Tzu’s lifetime. And as with the Bible, scholars are still debating the best translations of this famously challenging Classical Chinese text.

The counsel to be like water comes in a meditation on how to embody goodness. “The supreme good is like water, which nourishes all things without trying to,” another translation renders it. “True goodness is like water,” still another says. “It nurtures everything and harms nothing. Like water, it ever seeks the lowest place, the place that all others avoid.”

Later, in a series of reflections on paradox, Lao Tzu makes another observation on water: “Nothing is gentler than water, yet nothing can withstand its force.” Put another way: “Nothing in the world is as soft and yielding as water. Yet for dissolving the hard and inflexible, nothing can surpass it.... The soft overcomes the hard; the gentle overcomes the rigid.”

You can see the truth of this brief reflection in nature itself. Water need not take up much space to do its steady work. It reads terrain brilliantly, finding the tiniest crevice and pooling in even a near-imperceptible depression. It has the power to dissolve more substances than any other liquid. Even the least porous, most impermeable rock will eventually yield to water somehow—through erosion or slow absorption, harnessing the power of other conditions, expanding and then contracting wherever it can permeate. It does not hurry. Even if it might sometimes seem as if water is not doing much, but it’s there, ready and willing to sustain, slowly softening whatever it encounters.

Be like water.

I hear a call to steady presence, to patience, to steady resolve. This is not a passive way of being. Water feeds and nourishes, gathers and burrows. It seeks out every opportunity. It makes itself available. It takes its time. It finds a way.

How countercultural this might seem to us in the West—and also how natural it is in the East. To benefit the ten thousand things is to think of communal goodness, not individual. And it strikes me how we often forget that the collective has long been the priority in Eastern cultures—Jesus’s as well as mine. In those traditions, harmony and belonging are the noble goals—not to stand out, not to be seen as unique, not to be recognized as an individual. What might we have lost in not recognizing that our wholeness is in our interdependence, not our independence?

What might we have forfeited in valuing personal salvation and individual importance over communal health and collective wealth?

Be like water.

“Courteous as a guest. Fluid as melting ice. Shapable as a block of wood. Receptive as a valley. Clear as a glass of water,” Lao Tzu wrote. “Do you have the patience to wait until your mud settles and the water is clear?”

I would like to. I hope to. Gentleness is the way, more powerful than we often acknowledge.1

What We’re Growing: The City of Grand Rapids has an urban forestry program, and for over a year now, Tristan has been in communication with one of their foresters about getting another tree for the right of way between the road and our sidewalk. Finally, last week, a team showed up to plant a tree.

I was surprised that they were planting a non-native Yoshino cherry. In front of our house, we have a tall sugar maple, and to the side, a silver maple—both native species. The arborist explained to us that there’s really nothing natural about an urban forest and that the right of way between the sidewalk and the street is not an ideal place for any tree to grow. Also, she and her team have to address a host of problems unique to the city, including sewer lines below ground (our maples are not great for those) and power lines above (ditto). So while they do plant plenty of native trees, they also a few non-native species in the mix.

This conversation reminded me of the ways in which we humans have imposed ourselves profoundly on the land, such that other creatures have to grow around us and our things. Even a native plant that grows as it was designed to can be considered weedy if it punctures sewer lines or interrupts the pavement. In its truly native environment, a sugar maple would have grown in community not with sidewalks and utility poles but with other maples and American beech trees, perhaps some elderberry or prickly gooseberry, and, in springtime, Canadian violet, trillium, and hepatica blossoming in their dense shade.

We can be fundamentalists even about things like native plants. Yet the chat with the arborist reminded me of the importance of seeing things as they actually are, not as we wish they were. We have so transformed the world in which we live such that few places are any longer “natural.” What then?

So we have this Yoshino cherry, and we’re glad, and we hope it will flourish. If it does, it will bless its neighbors. In early spring, its blossoms will be a source of nectar for for bees and for butterflies and for any hummingbirds that have made their way north. Later, the berries will provide food for the birds. We will delight in its beauty, and I might even try to make some cherry-blossom jam.

What I’m Reading: I spent the first 13 years of my childhood in Southern Baptist churches. They were Chinese churches, though, so largely insulated from the stereotypical American evangelical subculture. We had our own ways. While other kids might remember playing “chubby bunny” in youth group and listening to contemporary Christian music, I remember heaping Styrofoam plates of rice, braised vegetables, and stir-fry. Still, I was reared to revere the Southern Baptist missionaries who helped to bring the good news to my people. So it filled me with some grief this week to read of the punitive actions that my childhood denomination took against several churches that have women in pastoral roles. One pastor who voted to eject the egalitarian congregations warned that churches that allow women pastors eventually “allow the marriage of homosexuals and then even allow homosexuals to serve as pastors.” To which I can only say: Let’s hope so.

I spent seven years of my education attending a school that was nondenominational in name but thoroughly Christian Reformed in origin, culture, and identity. This week, the Synod of the Christian Reformed Church met here in Grand Rapids. It did not go well! The Synod doubled down on its anti-LGBTQ+ positions. Dave Struyk, pastor of Community CRC in Grand Rapids and father of Ryan Struyk, who penned this moving reflection ahead of Synod, was among the allies of LGBTQ+ people who walked out in protest. I grieve, especially for the queer kids who will question their belonging not just to their congregations but also to God. “Could the power of Christ’s resurrection be enough to redeem all of creation,” Ryan writes, “even loving, covenantal relationships that look different than Adam and Eve did?” To which I can only say: Let’s hope so.

I am overwhelmed with gratitude at all the encouragement and all the raised virtual hands I received in response to my request last week for readers to give feedback as I work on my book manuscript. It felt so scary to ask and then so gratifying, when dozens upon dozens of you wrote me. And what a gifted, varied, interesting bunch you are! People on six continents! (Where are you, Antarctic people?) Retired teachers and librarians, young gardeners and trained horticulturists, recipe developers and child wranglers, those who bravely bear the sacred burden of being your family’s grammarians and those who simply like to read.

Simply by responding, you have surrounded me with a sense of community, so thank you. As soon as I have chapters to send you that won’t bring shame upon my family name, I will begin to get them out to a few of you at a time. In some form or another, you’ll hear from me no later than August 15th, but hopefully much sooner—a deadline I put out there as much for public accountability as anything else.

All right, it’s time to head to the farmers’ market. I harvested the first of our garlic scapes yesterday, and I think we’re having shrimp and grits for dinner, so I want to get some greens.

What are you wondering about this week? What’s growing in your garden?

As ever, I’m so grateful we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Yours,

Jeff

This essay is written in a traditionally Chinese style that you might have noticed it in my writing before. It isn’t a linear argument. Instead, it circles around a phrase or a concept, examining it from different perspectives, returning again and again from different angles.

You have poetic sensibilities--that’s why I am so thrilled to hold your “fragments,” read your non-linearity! Thank you for tending our gardens. With or in spite of regularity. Thank you for naming our tensions and holding them with us, thank you for your odes to bumblebees and cherry trees in our urban fantasies. “To be like water.” You are a gift to us all.

Let's hope so. Amen.

Thank you for sharing Lao Tzu's wisdom with us. It is good to remember that soft, patient gentleness can prevail. What a week! (Though it was delightful to see you and Amanda Opelt harvesting scapes at the same time. The delight of gardeners. 😊)

We are in the throes of figuring out how to convert the sprinkler system in our front lawn into a simple drip system for the grapes and pollinators we are replacing it with. We are tired, low-energy desk workers with no clue how this stuff works. But we will gamely watch videos and give it a go.