In Search of Joy

Some fragmented thoughts on family time, cooking for my parents, perspectives on COVID-19, and departed glory

Thursday, December 17

East Sandwich, Massachusetts

Hello, friendly reader.

This past weekend, I drove an hour and a half north from the Cape to my sister’s house. My parents, vaccinated and boosted, were visiting my sister and her family, so I, too, made my first visit since the Before Times.

A few minutes after I arrived, my mother did what she always does: She did inventory.

Almost immediately, she took me into the kitchen. Was I hungry? Had I eaten breakfast? On the counter were the Chinese buns that I liked, pillows of bread split in half and filled with cream. She opened the refrigerator: There were four boxes of cheung fun with shrimp, which she’d bought in Chinatown.

My mom had brought so many things for me to take home too: Chocolate-covered macadamia nuts. Toothbrushes and floss and toothpaste. Dried apples, which she’d made from fruit harvested from her backyard; Tristan and I once said that we liked them—they’re good in oatmeal—so now we get a regular supply. Two Ziploc bags full of dried beef; she’d used the beef to make stock, and she thought Fozzie might savor the remnants, which she’d painstakingly shredded and picked through to ensure there were no bits of bone. A large container of rich and gorgeous stock, simmered for so long that, when finally cooled, it grew thick with collagen and jiggled like jelly. (“There are a few pieces of tendon in there too,” she said, knowing that her stewed beef tendon is one of my very favorite things to eat—and one that I still struggle to cook properly.) Two wool scarves, one light gray and one dark gray, which she’d knitted for us.

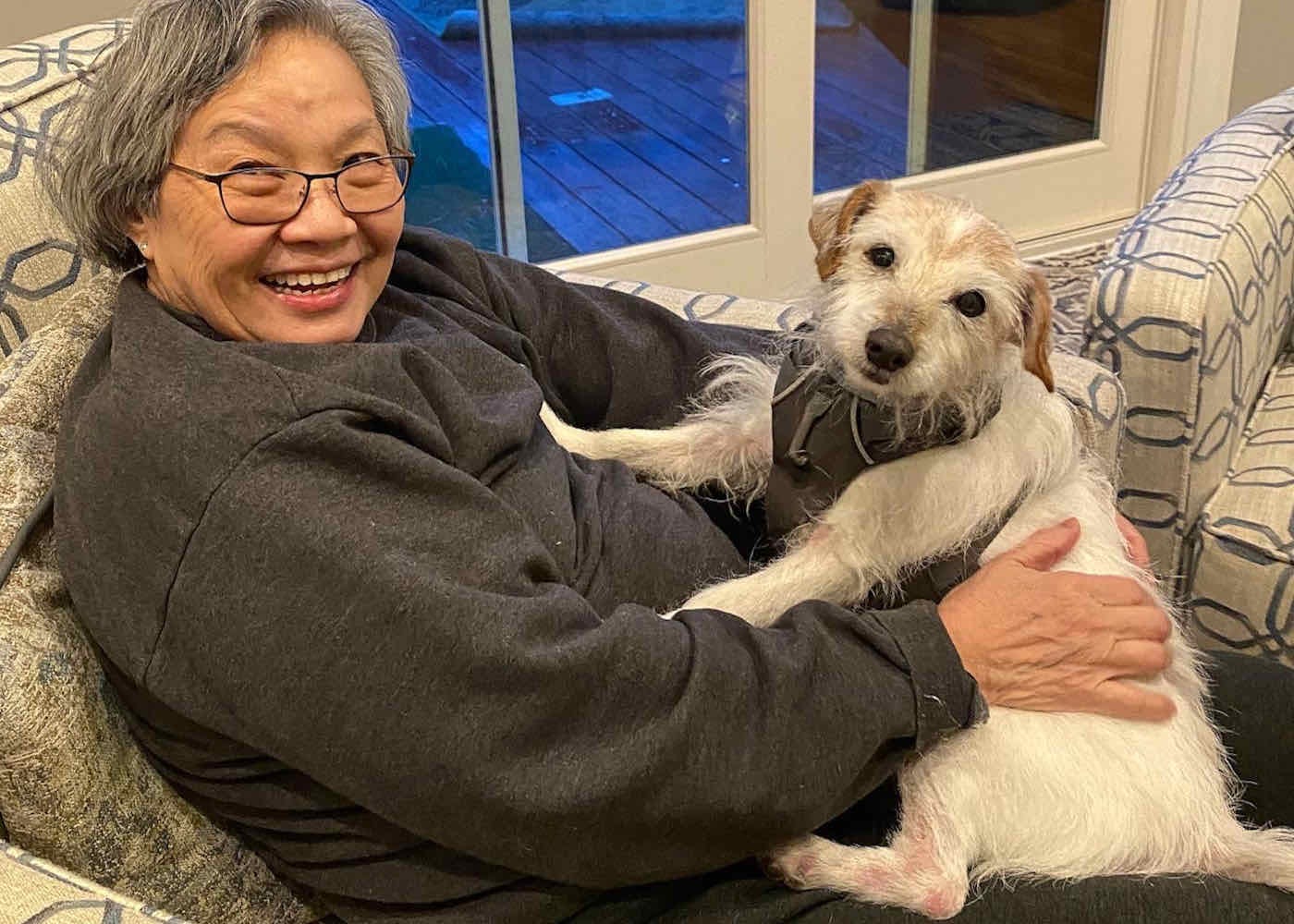

This was my mom’s tangible way of doing what she has always done: feeding, nourishing, making sure we stay warm. If you’ve ever wondered where my love of food and my interest in hospitality comes from, well, now you know. My mother is the one who taught me how to cook by sight and smell, the one who demonstrated how to get eight dishes on the table nearly simultaneously, the one who modeled the art of tending to others, the one who showed me by example how to achieve harmony on a menu. Her name is Grace.

I could also see that, after a week in a house full of kids, both my mother and my father were weary. They’d never admit it aloud. Instead, I read it in the finer details—for instance, the box of fried rice in the fridge, which, uncharacteristically, came from a restaurant.

As my parents sat in the family room, my mom knitting and my dad watching some kind of sportsball, I wondered whether we’d finally arrived at the crossroads that, for a while, I’d seen in the distance. In my heart, I imagine them still to be in their forties and seemingly inexhaustible. In reality, they are now in their seventies, and things just aren’t as easy as they used to be. The two of them have spent so many years, so much energy, caring for us and for our extended family and for their friends. Perhaps the roles are shifting. Perhaps it’s come time for me to cook for them.

On Sunday evening, I made dinner.

First, I shucked some local raw oysters and whisked together an apple and shallot mignonette. Then, I roasted a few pounds of tri-tip as well as some zucchini and rainbow carrots, because they’re vegetables that the kids won’t reject... usually. “What are those?” Alex, my 5-year-old nephew asked, pointing at the purple and yellow carrots. “Carrots,” I replied. “No, they’re not,” he said. “Carrots are orange.”

I made a quick shallot jus to accompany the roast beef, and of course we had rice. My 13-year-old nephew, Caleb, had told me he wanted to help, and he enjoys baking, so we made a batch of buttermilk biscuits too, because carbs are of God.

My mother obviously couldn’t leave me alone in the kitchen, not entirely. Before I went to the grocery store, she’d instructed me to get two pounds of tomatoes. One of my sister’s favorite dishes is egg and tomato, the traditional Chinese comfort food that I’ve written about before. My brother-in-law tried valiantly to make it for her not that long ago, going entirely on taste and logic; his version—eggs + tomato + ketchup + love—was not what my sister was expecting. So my mom did a brief cooking lesson for him. Though I’ve made this dish a thousand times before, even I got lost in her rapid-fire litany of sentences that began, “Then all you do is...”

Earlier in the day, I’d asked my father if there was anything in particular he wanted to eat. He inexplicably replied: “Chocolate soufflé.” I have never made a chocolate soufflé. I think I ate a bite of one once, in Paris, when Tristan ordered it at a bistro. But we live in wondrous times, and Google is our friend, so I found a recipe on the Interwebs, and my nephews and I got to work.

We melted the chocolate—bittersweet, which seemed right—and butter. We added egg yolks and vanilla (which Alex, with all the confidence and exuberance of his five years, felt no need to measure, taking the whole bottle and starting to pour until I said, “What are you doing? Did I tell you how much?”). We whipped egg whites into stiff peaks. We gently folded those egg whites into the other ingredients.

My sister had no ramekins, and the recipe called for ramekins. But as in every good Asian household, she had all manner of Pyrexes and oven-safe storage containers, because we do love our leftovers; dinner in a Chinese home is a failure if you’ve cooked too little for there to be leftovers. I found two round Pyrexes resembling large ramekins. We filled them with the batter and popped them into the oven with hope and prayer. The soufflés rose!

“That was a good dinner,” my dad said, after everything was finished and the leftovers packed away. (See above paragraph.)

Later that evening, as I prepared for bed, I remembered that it was Gaudete Sunday—the third Sunday of Advent, when those church traditions that follow the liturgical calendar focus on joy. Gaudete Sunday takes its name from the introit customarily sung during that Sunday’s Mass, which begins, in Latin, “Gaudete in Domino semper....” In English, it goes: “Rejoice in the Lord always; again, I say, rejoice. Let your forbearance be known to all, for the Lord is near at hand. Have no anxiety about anything, but in all things, by prayer and supplication, with thanksgiving, let your requests be known to God.”

Joy has never been the easiest thing for me to find, to feel, or to understand. Is it an emotion? Is it a sentiment? Is it a byproduct of some other spiritual virtue that I neither have nor grasp?

Maybe joy can be cultivated through careful attention and thoughtful response. Maybe joy springs from quality time spent intentionally among those for whom—and with whom—comfort might be fleeting. Maybe joy takes shape where grace is unexpectedly recognized and gratitude slowly emerges. Maybe joy grows out of a deeper story—out of forbearance, as the introit says, as well as out of mutuality, out of sacrifice, out of loyalty.

My relationship with my parents hasn’t always been easy. We differ on many things. But as an adult, I’ve come to recognize what I couldn’t as a child: That my mother and my father have always had the best intentions and the highest hopes for me and for us. That in their own way, they have tried to be faithful, first to their God and then to their family. That, though we hold distinct convictions on some serious matters, we also share bonds that transcend our disagreements.

Maybe joy is a discipline—not so much the bubbling-up of happiness as a movement toward contentment. Maybe joy wells up from a place deep in one’s soul, where the conviction endures that, as Julian of Norwich famously wrote, all shall be well and all shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well. “Shall be,” of course, because we can’t know the completeness of joy in this lifetime.

Before dinner, my dad had unspooled a characteristically Baptist prayer—a long and winding journey that at times seemed less meant for God’s ears than for those around the table. I almost laughed, because, though he was praying in English, it was almost as if he were channeling my preacher grandfather, who, after a stroke stole most of his ability to speak, could always summon the words to pray and pray and pray in Cantonese.

Maybe joy is what you feel when you can find the well-meant, heartfelt thing behind the thing. Maybe it’s the taste of the possibility of ultimate reconciliation. Maybe it’s the glimpse of the goodness of a hard-won love.

What I’m Cooking: The method I used for the roast tri-tip came from Serious Eats. The next day, I took the leftovers home. We made excellent roast-beef sandwiches. Fozzie got some of the beef as a special treat. And this morning, I took the rest and made fried rice for breakfast.

And here’s the recipe I used for the chocolate soufflé. It really was much easier than I imagined it would be.

What I’m Reading: As you know, I think a lot about what we eat and how we eat. A couple of weeks ago, I came across this profile of Birch Community Services, an intriguing operation in Portland, Oregon, that seeks to address food insecurity in innovative ways. One unusual aspect about this story is that the writer has personal experience with financial insecurity and describes the effects that participating in Birch’s program has on her and her family: “At the grocery store, people usually think about whether they can afford to buy something. At Birch, they start thinking: Is this the best choice for my family? Do we really need it? It took time, self-reflection, and a determined mouse who started nibbling at our pantry’s overflowing provisions to help us realize we did not need to take it all.”

This past week, the United States passed a tragic milestone: 800,000 people have now died from COVID-19 in this country. The number is staggering—and perhaps so large that we struggle to grasp the toll. Against that backdrop, I found this essay, written by Matthew Walther, who lives no more than 100 miles from our home in Grand Rapids, to be particularly stunning and sad. I suppose I should be grateful that he is willing to put into stark black and white what others refuse to say except implicitly: “No one cares.... [O]utside the world inhabited by the professional and managerial classes in a handful of major metropolitan areas, many, if not most, Americans are leading their lives as if COVID is over, and they have been for a long while,” he writes. “[T]he virus simply does not factor into my calculations or those of my neighbors, who have been forgoing masks, tests (unless work imposes them, in which case they are shrugged off as the usual BS from human resources), and other tangible markers of COVID-19’s existence for months—perhaps even longer.”

He did not write any of this with any regret or any remorse. He tells us that none of his children has ever put on a mask. He has not received a booster shot, and claims that nobody he knows has. Indeed, he has chosen to change almost nothing about his daily life: “In 2020, I took part in two weddings, traveled extensively, took family vacations with my children, spent hundreds of hours in bars and restaurants, all without wearing a mask.”

Two particularly striking things to me about his framing of COVID. First, he paints our divisions about COVID as a matter of class, identifying himself with what he calls “the lower orders.” Yet there is no acknowledgment of the reality that those “lower orders” have been disproportionately hit by this pandemic; multiple analyses of COVID’s toll have found that startlingly higher fatality rates are “associated with high poverty levels, especially in areas with low population density.” In other words, rural, poorer regions like Walther’s have borne the brunt of this pandemic, yet those deaths, that suffering, has done little to change daily behavior. Secondly, his bio tells us that Walther is the editor of a Catholic literary journal. Yet, conspicuously, there is not one mention of social good, or of mutual care, or of Christian love.

Finally, my friend Sarah Bessey’s latest installment of her newsletter, Field Notes, is a word of solidarity and hope for anyone who has been disappointed by the Church. It’s beautifully honest and tender, just like she is. As I tweeted earlier today, she and I have a half-joking, long-running debate about depravity, and I really wish humans would make it more difficult to believe that depravity actually real.

As we move through these final days of Advent, I hope and pray that you will find glimmers of goodness and signs of grace around you. May the busyness of holiday preparations not swamp you. May your worry pale in comparison to your hope. And may you find ways to embody for others the very same love that you long for.

I always love to hear from you, to know what’s stirring in your hearts, and to learn what’s on your minds. If you’ve got something you’d like for me to be holding in prayer, feel free to share it.

As always, I’m so glad that we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Much love,

Jeff

I am writing this reflection of the the Atlantic article as someone who has been living in NYC for the entire pandemic. Here are some disjointed thoughts.

How easy it is for me to reject the broad stroke that Matthew tries to paint me into. How often in my thoughts of those I disagree with they would also reject how I paint them.

How blessed is Matthew and his family to have had a time mostly unaffected by covid. To not have been the cause of someone’s death because of a wedding or birthday party or Bible study. Others did those same things and now 800,00 people are dead in the United States. As we have seen human connection is so vital I understand why people would take those risks even if they don’t see it as risky.

I feel so sad that Matthew has such little empathy for those to have lost so much more than him to this pandemic. I also must turn that critical eye to myself and question how often I have accepted my blessings without a thought to others unless it directly intersects with my life. As someone who has not lost any family how easy is it for me to know the numbers, but not process them as real people. For everyone who died was a child of God. Everyone who died was part of a community that now morns them. How expansive has our loss of human life been and yet dinner needs to be made, an email needs to be answered, the dog needs to be taken out; our lives still go on. Only God truly understands the loss, but let us try not to let our hearts be calluses over because we have heard the death counts so many times before.

What a lovely tribute to your parents. I also struggle with holding some intensely different perspectives from my family of origin. I think you're right- at the end of the day, I love them and they love me. We can find some commonality there.