Lessons in Love

Some fragmented thoughts on 1 Corinthians 13, the testimony of young people, a new book of blessings, and the beauty of a blossoming orchid

Saturday, February 11

Grand Rapids, Mich.

I returned home two days ago, gentle reader, from a visit to the University of Georgia. On Tuesday evening, I had the honor of preaching at the Presbyterian Student Center’s weekly worship service. Then, on Wednesday afternoon, some students and I sat and talked—about our fears, our faith, our longings. What a privilege. What a gift.

Before the trip, I had the beginnings of something written to you. But after—after sitting with these students, after receiving snippets of their stories—I scrapped them and started over. Instead, I’d like to share a little of what I told them as well as what I learned from the students.

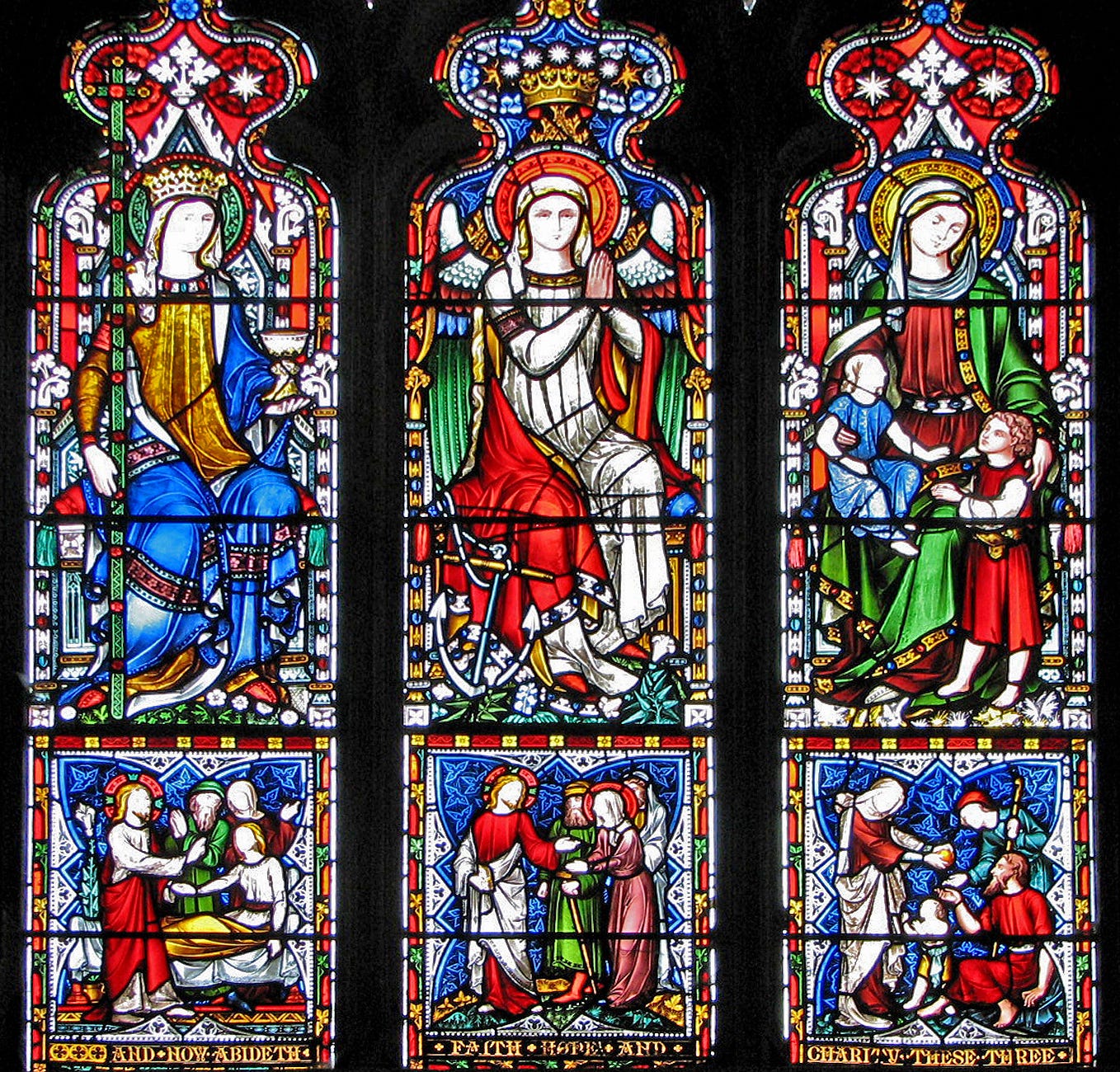

Pastor Haley Lerner, one of the Presbyterian Student Center’s two campus ministers, had chosen a passage from I Corinthians 12 for Tuesday’s worship. It’s that portion that talks about the different parts of the body, their distinct roles, and their mutual necessity—a common choice when one wants to honor diversity. But that section only makes complete sense if you keep reading into I Corinthians 13. As I reminded the students, the chapters and verses were imposed centuries after the letter was sent to the Corinthian church. Back then, they wouldn’t have stopped at the chapter’s end, because it wasn’t an end. They would have kept reading, into the part where Paul writes about love.

It’s only divine love—patient love, kind love, humble love, self-sacrificial love—that can hold the fractious body together.

Here’s part of my homily:

The lies that we tell others and the lies we tell ourselves—they erode the love that God has written into our very bodies and souls. The lies corrode the beauty, the good. We start to believe that we’re dispensable. And the only thing that can bring us back, the only thing that can ultimately heal, the only thing that can return us to where we belong is divine love itself, which comes to you through a friend’s whisper or a pastor’s embrace, a gentle breeze in the summer heat or a splash of life-giving water on your face, a memory of being cherished or a surprising reminder, even one you might have to give yourself sometimes, that you belong—because you are God’s beloved. Do you believe it?

I won’t lie: Some days I still don’t. Some days, I only want to believe it. Such faith seems just beyond my fingertips and well beyond my tired heart. Some days, my fears get the better of me—fears of rejection, fears of not being good enough, fears that my skin or my sexuality will mark me as unworthy, fears that my inward shame might show itself on the outside, fears that the things others have said might actually be true after all.

Which is why I still have to tell myself every day that God loves me. God’s love and grace are etched into every remarkable cell of my body, every gorgeous part of your being. It doesn’t mean you or I are perfect. But that was never the deal this side of heaven. It does mean we’re loved.

Another hard part: Do you believe that others belong, even people you don’t like, even those who have hurt you? Do you believe that others belong, even the ones you find toxic or awful, even those whose words and actions bring harm to the world? Do you believe that this love is for them too?

Over time the lies that we tell about others—even the people who tell lies about us—erode the love that God has written into their very bodies and their very souls. We begin to see them as less than. They eat away at all the beauty, all the good. And the only thing that can bring us back, the only thing that can ultimately heal, the only thing that can offer true redemption, is divine love itself—because they, too, are God’s beloved. Do you believe it?

Paul does a curious but crucial thing in this passage: He doesn’t define weakness or what he means by less honorable. He just talks about “those parts of the body that seem to be weaker” and “those that are less honorable.” There’s both a generosity and a rebuke in that: Each of us can identify something in those around us that irks us or makes us uncomfortable or angers us or even hurts us. And again—let me say it one more time—the only thing that can bring us back, the only thing that can ultimately heal, the only thing that can offer true redemption, to the entire broken yet beautiful body of God’s dear ones, is divine love itself. Do you believe it?

Again, I won’t lie to you: Some days I still don’t. Some days, I don’t want to believe that God’s love is so expansive that it would cover not just sins I’ve committed but also sins done against me and sins done against this unfair world’s most vulnerable.

Which is why I still have to tell myself every day that God loves even those whom I struggle to love. God’s love and grace are etched into every cell of their bodies and every part of their beings. Let me be clear: That doesn’t excuse any harm they might have caused. It doesn’t mean you need to act as if no wrong has been done. And it doesn’t mean they’re perfect. But that was never the deal this side of heaven. It does mean that they too are loved.

As I greeted students afterward and then again the next afternoon, I received some stories of the harm and the wrong inflicted on these young people, especially those who identify as queer. Even now, youth are being told that their salvation is at risk because of their sexuality or their gender identity. Even now, they are absorbing the message that love is conditional—their family’s love, their church’s love, their God’s love. Even now, they wonder whether it’s possible for them to belong—to their families, to the Church, to God.

It grieves me deeply that these young people must walk this terrain, which I and so many others know too well. And also: The community that walks with them at school—including the deeply loving pastors and the wise-beyond-their-years peers who are embracing them—gives me such hope that they’ll find their way, perhaps (I hope) more quickly than I did.

One student named Kaz urged me gently but firmly to put more meat on the homiletic bones. It’s fine that I kept talking about love. So many preachers do. But what does it mean, they wanted to know, in practical terms?

Kaz works at the campus Pride Center and often finds themselves in conversations that demand a particular kind of care, a special type of tenderness. Students confide in them about difficult circumstances and tough relationships. They need help. Kaz asked me to apply the principles I’d preached about to those conversations. How does one act justly and lovingly? They wanted to honor the person seeking help, yes. And in doing so, they also sought not to denigrate or malign any people who had done that person harm. How?

What heart! What I learned from Kaz is that, with great care, we can do multiple things at once: We can tend to the wounded soul in front of us while also honoring the hurting souls who have in turn inflicted wounds on others. From Kaz’s innate respect for human dignity, I got a much-needed reminder that we need not operate according to the world’s scarcity models when it comes to divine love.

Another student showed up with a guide dog in training. She—the student, not the dog, who was overjoyed to be around so many people—seemed really nervous. So for a little bit, we just talked about the dog. But then some profound questions emerged about welcome and belonging—really, her experience of the lack thereof. And then we talked about the dog some more.

What tender spirit! What I learned from her—what I saw in her example—is that the best answers to those questions come not from an outsider but from within. What might have seemed at first like a conversation full of non-sequiturs was actually all of one beautiful piece. She actually already knew what to do. In her care and nurture of a creature that is being trained to care and accompany another, she’s already living out the answers that she’s looking for. We create the goodness and the justice we seek. In tending to the needs of others, we can find what we’re looking for too.

A third student who comes from a religious background not that different from mine told me about the soul-crushing compromises we sometimes make when we’re back in our childhood congregations as well as the alienation we can feel when folks we’ve known forever begin to recognize that we might not be quite the same person they thought they knew. She wanted wisdom for how to navigate such circumstances.

What courage! What I learned from her was the power of showing up. This student had chosen to be present. The answer she longed for was already right there in her chair. In her resilience, in saying “no” to the naysayers, in her embodied longing for God’s love, she was testifying to a greater love. Here, in a place where she was welcome and a place where she could be wholly herself, she could find the nourishment she needed to strengthen her to show up authentically everywhere else. We, too, can find sustenance and solace in places that feed our bodies and our souls, bolstering us for the harder and harsher places that we’re bound to encounter.

Whatever knowledge I might have brought into the room paled in comparison with the wisdom we were able to tap into together. And what I learned from all the students I met at the University of Georgia is that sometimes you’re invited into the room as a teacher, but the best and most beautiful part is suddenly realizing afterward that you got to be a student too.

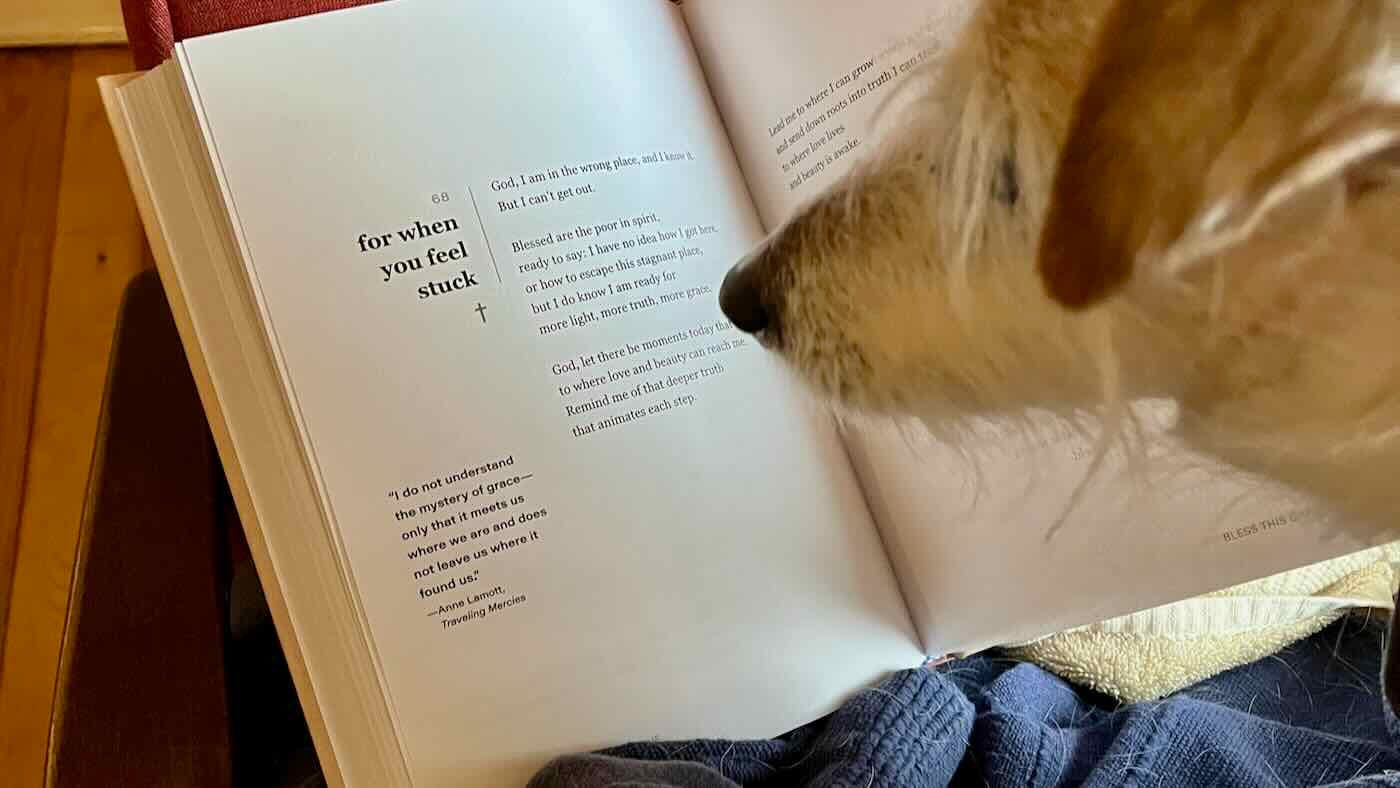

What I’m Reading: When I got back to Grand Rapids, I found a blessing in my inbox, written by Jessica Richie and Kate Bowler, the co-authors of The Lives We Actually Have: 100 Blessings for Imperfect Days. Some of you might remember that I interviewed Kate in the fall of 2021, when her book No Cure for Being Human was published. Then, last year, she turned the tables on me: she interviewed me for her podcast, Everything Happens, which Jess produces. And in early December, I was able to spend some time in person with both of them, eating potato chips and sipping champagne, and I have to tell you, they are the loveliest.

Their new book is a beautiful gift, especially for those of us who struggle with words like “blessing.” Maybe you’ve been the person gossiped about as the church lady ends the anecdote by saying, “Bless her heart.” Maybe you’ve craved blessing that hasn’t come. Maybe you’ve believed the lie that if you do just a little bit more or work just a little bit harder, then finally those blessings will come pouring down. This book is an antidote to all that. There are blessings for quotidian situations—“for small steps when you feel overwhelmed,” say, or “for when you’re running on fumes”; I have a feeling that I will be reading “for when you’re feeling grouchy” on a regular basis. There are blessings for life’s bigger challenges, too—“for aging gracefully” and “for learning to love yourself” and “for when so many are suffering (and you don’t know what to do).”

In Hebrew, the word for “blessing” shares the same root as the word that means “to kneel.” This is apt in multiple ways. If you imagine that God is ginormous and we are small, for God to bless us might mean that God must come down to our level. For us to bless God might invite us to bend a knee in praise. But then there are the times when life forces you to your knees—times when you could use an extra measure of blessing.

The blessings Jess and Kate have written combine the bracing candor of the psalms with a clear-eyed recognition of the realities of our modern lives. Thank our good and gracious God for their shared gift of wit, too, and thank God for people who have been through some stuff.

Kate and Jess sent the below blessing to me because they wrote it especially for you, the readers of this newsletter. What a perfect coda it is for my time in Georgia—and, really, what an apt word it brings for all of us trying to navigate the hard truths of being human.

A Blessing for When You Want to Experience Belonging

Blessed are you playing the stories of who you are through your mind like a filmstrip. Where you got your laugh or love of music or those terrible navigation skills. You who can pinpoint yourself on a family tree. You who know exactly whose you are.

And blessed are you when you don’t belong. When you can’t explain exactly how you ended up here, Outside of what was acceptable. But longing to fit in nonetheless.

Blessed are you in the alienation and the fear, The “where will I find my people” The confusion or anger or the still-wounded from unbelonging.

May you feel your own worthiness. May you feel your own belovedness. May you find yourself wrapped in a story larger than the one you can trace. A story of love and hope and courage A story truer than the one you’ve been told.

Blessed are all of us here, in this family of God.

Amen and amen. You can get “The Lives We Actually Have” here—and anywhere else good books are sold.

What’s weighing on you this week? Where might you crave blessing? What lessons are you learning in surprising ways and unexpected places?

I wish you glimpses of beauty and encounters with delight. Here in our house, that meant an orchid that not only didn’t die under our care but also actually blossomed.

That’s all for this week. As always, I’m so grateful we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Yours,

Jeff

What a fantastic read. sadly, I almost scrolled past it. Thankfully, I am finally getting better at listening to G-D's whisperings, rather than staying strictly to my self made time table.A most tender and profound piece. How fortunate, the young students are receiving these words of wisdom, truth and beauty.

I love how you always close your posts with "I'll try to write again soon." Such a classic line between letter writers. Thank you.