Love Your Neighbor

Some fragmented thoughts on fences, carrots and potatoes, shadow puppets, wartime poetry, and prayers that God might show up for us and in us now

Wednesday, November 22

East Sandwich, Mass.

The sun was already starting to sink in the sky one afternoon a couple of weeks ago, when Fozzie and I went to the community garden to clean up. By mid-November, each gardener has to remove anything that can’t be composted or tilled back into the soil. So we retrieved the tomato cages and pulled up the stakes that I’d put in as supports for various plants. We also dismantled the fence that I’d set around our garden plot.

Our garden neighbor, Roger, was there too, to tidy his plot. Roger’s set-up is always much more elaborate than mine. I guess it’s a bit grand to call my fence a fence: Where I had my rudimentary stakes driven just a few inches into the ground and basic rolls of chicken wire that I’d bought on Amazon, he had four-foot-tall fencing with solid wooden posts.

As we worked, he asked if my fence had done its job: “Did it keep the animals out?”

He thought he knew why I had put it up, and I almost had to laugh, given how kindly he asked. Where Roger had a swinging gate, complete with hinges and a latch, the entrance to my growing area was just a gap in the chicken wire, through which any creature could easily have strolled.

“Oh, it wasn’t meant to keep anything out,” I said. Though rabbits live in the neighborhood, I’ve not had any trouble with them, and anyway, they could easily have jumped over my fence, which was only 16 inches tall. What damage I had this year was entirely the work of much tinier creatures that have never been much bothered by fences—the bean beetles, which ravaged my bush and pole beans, and slugs and caterpillars, which mostly stayed away until I planted my fall crop of bok choy. “I put it up so that Fozzie would stay in.”

He laughed, we continued our work in amiable semi-silence, and I thought about that old Robert Frost poem in which one man insists that good fences make good neighbors. Really, I think good neighbors make good neighbors.

My fingers slowly untangled and discarded the desiccated vines of long-dead morning glory and frost-faded stems of chicory, which had braided themselves into the wire. In one section, the thick stalk of a sunflower had woven itself through the hexagonal steel. In another, volunteer grape-tomato plants had made my fence their scaffolding. Fozzie and I slowly worked our way around all four sides of the plot, suffering through the tedium of separating dozens of feet of the metal I’d installed from so many varieties of nameless weed that had enmeshed themselves in just a few months.

So much of this was, of course, evidence of my carelessness and neglect: I could have addressed those weeds. I should have attended to the chicory and the morning glory, which showed up in exactly the same places the season before. A wiser gardener would have learned lessons, would have showed more discipline, would have saved himself a lot of trouble. But it was just easier to let the fence grow, until it wasn’t.

“It takes a lot more time to take this fence down than it did to put it up,” I said.

“That’s for sure,” Roger replied.

What I’m Growing: Two weeks ago, I harvested all the carrots from the backyard—a whole bunch of purple and yellow ones, but also a few orange, though those are the ones Tristan likes least. Then I went down to the basement and packed about ten pounds of potatoes; they’re mostly a red-skinned variety called Desiree and a yellow-skinned one called Vivaldi, but I suspect there are a few Yukon Golds in there too, which I grew from potatoes that I’d let languish for too long in the refrigerator.

As usual, we are on Cape Cod for most of November. We’ve been coming here for more than 15 years, and it has become a special place for us, with so many memories. Among them: This is where we got married, right in the backyard.

It’s such a gift to be a long-term visitor to a place—to return again and again, to learn more about it and its history, to appreciate aspects you didn’t notice before. Even as it changes—summers are definitely hotter now, the waters less clean—we change too.

Fifteen years ago, I had never grown a carrot or a potato, couldn’t have told you what either’s leaves looked like or when to harvest, and had no idea that carrot tops were edible, let alone made for a delicious pesto. Fifteen years ago, I didn’t know how to shuck an oyster, didn’t know the difference between the Nauset and the Wampanoag, didn’t know anything about how they were the ones who had grown vegetables here and harvested oysters here and fished the waters here for generations.

I am thankful, for these things and for so much more, and tomorrow, many of us will sit around tables with loved ones—annoying ones, perhaps, or exasperating ones, maybe, but loved ones nonetheless—and we will express our gratitudes. What then? I wonder. What then? What then in a world that still holds so much ache and grief? I guess my hope is that our gratitudes won’t be shared merely in vanish mode but that they will somehow move us—move us beyond ourselves, move us beyond this particular moment, move us to be just a little more gracious, just a little more loving, just a little more... just than we were the day before.

What I’m Listening to: Spencer LaJoye has a stirring new song out called “Shadow Puppets.” If you don’t Spencer’s work— well, I hope you’ll soon acquaint yourself. Their voice is wondrous—and their lyrics! “That shadow is big, that shadow is wide,” they sing. “It’s a darkness that I fit my whole self inside.” In an interview with Glide magazine, Spencer said, “I confess that I tend to let my darkness swallow me up, even though I have every capability of separating myself from it enough to see it more clearly and treat it with a little compassion.” Me too. This is the title track of their upcoming album, which I believe will be released early in the new year. Can’t wait.

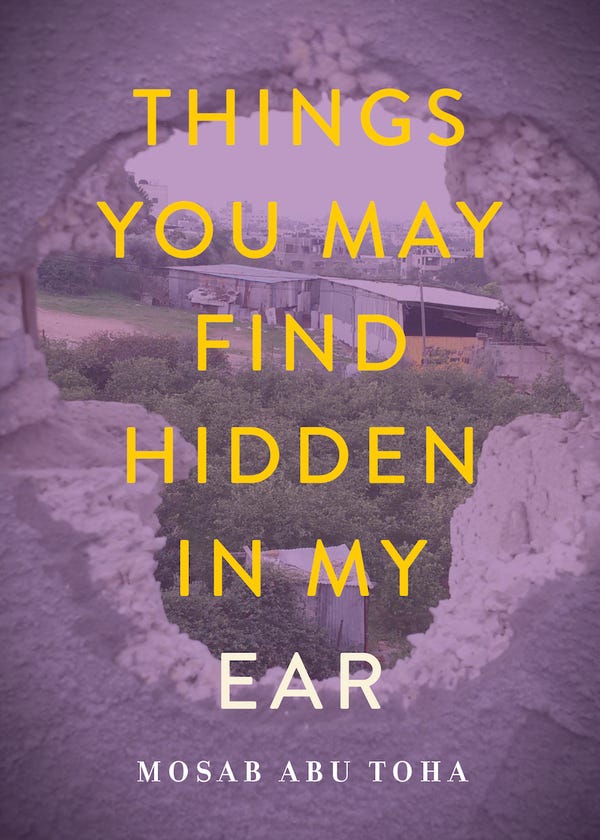

What I’m Reading: Before October 7, the poet Mosab Abu Toha lived in the northern Gaza town of Beit Lahia, which is less than three miles from the Erez checkpoint to Israel. While he and his family were sheltering in the Jabalia refugee camp last month, their home was destroyed. Then, last week, they fled southward on foot, perhaps hoping to get to the border with Egypt; one of Abu Toha’s sons was born in the U.S. and is an American citizen, and the family was said to be on an evacuation list. But Israeli soldiers who stopped them en route took Abu Toha into custody. After a couple of days, he was released, but I have to wonder: What if he had not been an internationally known, award-winning poet? What if he had been just another son, just another husband, just another dad, just another person trying to build a life amidst rubble?

I suppose I am most grateful for Abu Toha’s writing because it describes, with witty candor and ridiculous grace, what it is like to be an ordinary person in Gaza. He invites readers’ compassion but has no use for their pity. Every poem bursts with resilient life. The grandson of Palestinians who were forced from Jaffa in 1948, he writes with a wry, vibrant manner, an affection for nature, and a clear eye for the absurd. His poems are beautifully drawn dispatches from a land that most of us will never visit—a land that most of its residents never intended to call home. Each one I’ve read, each with its carefully observed details and its unexpected grace notes, has reminded me of the complex reality of human existence. Even, perhaps especially, amidst devastation, one must find laughter, must hold onto memory, must cultivate love—because that is what it means to hope, to persevere, to survive.

Two favorites:

First, “We Love What We Have,” which features in Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear, Abu Toha’s award-winning 2022 collection. You can read the whole poem on the website of Expedition Press, a lovely Seattle-based letterpress that has created a broadside of this piece, but I can’t stop thinking about its opening lines, which remind me that we live because of love:

We love what we have, no matter how little, because if we don’t, everything will be gone. If we don’t, we will no longer exist, since there will be nothing here for us.

Then there is the surreal “The Fish and the Refugee Camp,” which is exactly what the title suggests: a fish visits a refugee camp.

San Francisco’s legendary City Lights Books is currently offering a free digital download of Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear “as a gesture of love, a tribute to our dear friend, and in fervent hope for peace.”

I know I’ve been delinquent with my letter-writing. Every time I’ve sat down to write, I’ve felt overwhelmed. I cannot make sense of the daily onslaught of the news or the cacophony of the commentary—and then I remember that what we see, which is already so much more than we were ever equipped to process, isn’t even the half of it, or the quarter, or the tenth. This is the violent mess of the world.

How long, O Lord?

I confess, too, that I had no idea that so many people were so multifaceted: Middle East policy experts as well as scholars of Frantz Fanon as well as authorities on the global media as well as analysts who can perceive the private motivations behind social-media silence.

How long, O Lord?

Let me leave you with a prayer. It’s a follow-up to, maybe even a continuation of, the one I wrote last month. These words came slowly—lately, my prayers have felt more like wordless groans than anything else—and they still feel so insufficient.

How long, O Lord?

I’ve been thinking so much about how God is said to show up and a few of the metaphors, limited as they might be, that the ancients used to describe some facet of the divine. Some days, we can only hope for the smallest suggestion of the divine, only wish for the tiniest flash of light—and some days, even that hope and that wish feel impossible to articulate.

As I wrote, I had in mind not just Gaza and its residents, the Palestinians who are suffering devastation upon devastation while carrying the unhealed wounds of so many generations but also the people of Israel, especially those who are wondering whether their loved ones will ever come home, and my Jewish friends who are enduring the grievous resurgence of anti-Semitism. Not just this particular manifestation of the human propensity to hatred and warfare, or this particular set of feckless political leaders but also other sorrows and other stories, especially those that have been unfolding far from the headlines. That some of these stories are under-covered, or perhaps even uncovered, might reflect disparities in the attention economy; why, for instance, have thousands been slaughtered in the devastating civil war in Sudan, yet that conflict gets so little coverage? Not just the events with geopolitical importance, but also those many stories that are deeply personal—devastating diagnoses and bedeviling predicaments, spirit-level troubles and private traumas. The weight of these things is significant too.

In response to last month’s prayer, I received one particularly scathing rebuke. A woman wrote to me to argue that those on the other side, for lack of better terminology, did not deserve to be remembered to God. I understand the anger. I acknowledge the deep pain. And also: It remains my firm conviction that, at the heart of it all, there are ultimately no sides when it comes to humanity. We are all God’s beloveds, all in need of intercession, none beyond the reach of divine grace.

Though I know that no prayer will feel right for everyone, I hope you might find some resonance somewhere in its lines.

God of the dove, Where are you? Be with all who cry out in sorrow, all who shout for help. Be with those who grieve and those who are still waiting. Show us a sign of unexpected hope. Let us glimpse an olive branch. God, come near.

God who is like a brooding hen, Where are you? Nudge us to be more like you— Shield for the vulnerable. Compassionate and faithful. Shelter for the weary. Attentive and kind. Empower us to be agents of grace. God, come near.

God of the sparrow, Where are you? Be with all who wonder if they have been abandoned, all who feel overlooked. Be with those who can only wish to cultivate a garden, those who yearn to walk without fear in the lands that hold their stories, those who wonder if they will ever again feel at home. Stir our imaginations. Sustain our dreams. God, come near.

God who is like a vigilant eagle, Where are you? Help us to be more like you— Seeing with empathy and clarity. Tender and steady. Moving with courage and care. Present in solidarity. Compel us to work for liberation and love. God, come near.

May you feel God’s presence near you in these difficult days, whether in the embrace of a friend or in the aria of a songbird, a surprising sighting of beauty or an unexpected encounter with grace. May you sense blessing all around you, and in gratitude, may you in turn bless the world with your love.

I’d love to know what you’re grateful for, if you’d care to share.

As always, I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

Much love,

Jeff

I am grateful for the marbled swirls of ruby and white in the beetroot I just picked and peeled from the garden. That “surprising sighting of beauty” helped me glimpse God’s presence for a moment in the mundane; helped remind me that They are a God of bountiful beauty.

Really loved this. Thanks so much for sharing.