Making Homes and Planting Gardens

Some fragmented thoughts on where one lives, Jeremiah 29, transplanted irises, church photographs, and Pete Buttigieg

Friday, May 19

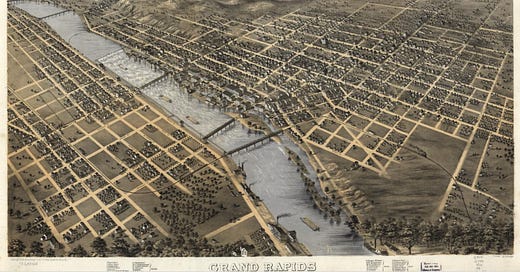

Grand Rapids, Mich.

Tomorrow, we’ll head to our small, local airport and embark on another adventure.

If we’re not checking bags, we can typically leave our house an hour before the flight and be at the gate before boarding begins. Recently, we got to the airport, and there were six or seven people ahead of us in the security line: Where did these crowds come from? On the return trip, if all goes well, I can be flopped on our sofa thirty-five minutes after the plane’s wheels touch the tarmac. The ease of flying in and out of GRR is one little thing we love about living in Grand Rapids.

Undoubtedly, while we’re traveling, someone will ask where we’re from, and we will say, “We live in Grand Rapids.” That usually sparks questions, some of which might even be asked aloud: “Is that where you grew up?” (No.) “What brought you there?” (A one-year, part-time job.) Occasionally, someone who is particularly blunt will simply say, “Why?”

Because we like it?

I lived in New York for 12 years; Tristan was there for many more. While we’re grateful for our time there, we were ready for something else—and we aren’t the only ones who felt this way. The New York Times published some interesting stats last week: New York City, San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Jose—all are losing people by the thousands to smaller, more affordable metro areas. But we are outliers, apparently, in having moved to Grand Rapids.

These fertile soils have long drawn settlers: First, peoples of the Hopewell cultures, who inhabited what’s now Michigan and Indiana for some 700 years. Then, a few centuries ago, the Peoples of the Three Fires—the Odawa, the Ojibwe, and the Potawatomi—built communities here, near the rapids on the river they called Owashtanong (“far-flowing water”). In the early 1800s, the first European trading posts popped up on the banks of what’s now the Grand River.

The French were followed by waves of immigrants from the British Isles, then Irish and Dutch, then Poles and Germans and Sicilians. African Americans from the South came during the Great Migration, Mexicans and Tejanos in the 1920s. Puerto Ricans began arriving in the 1950s, then Vietnamese refugees in the late 1970s. All that has made for a metro area that is much more diverse than the stereotypes: About 75% of the population is white—almost exactly in line with the demographics of the entire U.S. The City of Grand Rapids as well as its two largest suburbs, Wyoming and Kentwood, are now estimated to be just 60% white.

Change, it seems, has been a constant—and so has resistance to change. Fierce battles were fought in precolonial times over prime agricultural land and rich hunting territory. In 1925, thousands of KKK members flocked to Grand Rapids for a parade that pointedly went through the heavily Catholic West Side; the Klan was as anti-Catholic as it was anti-Black. In the 1930s, the city was redlined; our neighborhood was graded “yellow”—one rung from the bottom.

Today, Grand Rapids and its environs are grappling with the same sociopolitical dynamics that the rest of the country is. In our neighborhood, it’s rare to walk down a block that doesn’t have at least a couple rainbow flags on display, and last year, our congressional district voted to send a Democrat to Congress for the first time since the 1970s. Yet one of our neighborhood bakeries enthusiastically participated in an effort to recall Gov. Gretchen Whitmer because of COVID mandates. In Ottawa County, immediately to our west, a public library was defunded by voters because LGBTQ-friendly books are available on its shelves; it may shut its doors next year. And the Ottawa County Commission was taken over by right-wing Republicans, who recently abolished the county’s diversity, equity, and inclusion office, ousted the head of the local health department, changed the county motto from “Where You Belong” to “Where Freedom Rings”.

It can seem overwhelming to exist in the midst of powerful crosscurrents. But what choice do we have except to try to live faithfully, to be good neighbors, and to create some beauty where we can?

Grand Rapids’s city motto is Motu viget—“strength in activity.” Perhaps that’s a semi-toxic expression of the American work ethic, as if rest were weak. But we have found strength and growth and even respite in our activity, in our life, here. That’s how I wish to read it anyway.

In the yard, the peonies that my mother sent are budding. I planted blueberry bushes and milkweed last year too, and those evidently survived the winter. Last year, I rescued some bearded irises from my neighbor Sally’s yard after she moved away; they are now blooming, and there’s something heartening to me about the fact that they’re a collaboration.

Fozzie is snoozing on our living-room couch. He’s a transplant, too, from Indiana. Despite his achy hip, he’s been accompanying me to the community garden every afternoon. Recently, Tracey, who lives down the block, told me that she finds the Fozz inspiring, which made me laugh. Should I tell her that he pooped all over the house last night? Anyway, he’s still alive.

Our 100+-year-old American Foursquare house has been through some abuse. What other word would be appropriate to describe slathering brown-black paint on solid oak floors and all the wood trim? But Tristan has spent a lot of time learning new skills over the past few years. Though we had professionals strip and restain the floors, he has painstakingly and beautifully restored not only the doorframes and window frames but also the banister and five doors so far. He’s now working on re-plastering the guest room.

Yesterday, a box arrived with paint for my study walls. In my entire adult life, I’ve never had a study. But here in Grand Rapids, we can afford a house that has space for a study. Soon, we’ll repaint that room, and have people who know what they’re doing put up wallpaper, and install bookshelves, and create a better place for me to work.

Later today, I’ll go by a neighbor’s house to buy some seedlings; she’s raising money for fertility treatments. I also ordered seedlings from a local organic farmer who is in her late 20s; what a brave thing to do to try to make your living that way. Maybe that’s another way a community can find strength in activity—by choosing whom to support, by spending wisely, by helping one another find flourishing.

Of course no place is perfect, and I have my own petty list of gripes. For instance, we went out for Chinese food here once. Those tepid dumplings and those wan vegetables: Every dish was an insult to my ancestors, and every bite stirred shame, and I thought remorsefully of that pig that died in vain. Maybe each time we welcome local friends to our table, what they eat can tell a better, more honorable story about the cuisine of my people.

And also: As much as I am making a home here in Grand Rapids, I still struggle to call Grand Rapids home. In some ways, I feel like an expat, much as I did when I lived in London. I’d never describe myself as a Michigander. We know some folks here, but our community isn’t what you would describe as robust. I have never eaten a wet burrito or an olive burger, nor have I visited the Ford Presidential Museum or been to the Grand Rapids zoo. (A couple of days ago, one lady said to me, “What do you mean you’ve never been to the zoo?” I thought the words were pretty clear.)

Sometimes I think about the ancient counsel that the Prophet Jeremiah sent to the exiled Israelites: “Build houses and live in them; plant gardens and eat what they produce... Seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you,” he wrote, boldly claiming that he was speaking for God. “Pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.”

I don’t exactly consider myself in exile here in Grand Rapids, except in the sense that I feel a little bit foreign no matter where I go. If no place feels exactly like home, there is an invitation to create a little bit of home wherever you are. Here, we are building a life that suits us. I hope we are being good neighbors and, in some small way, making it a better place too. Maybe that’s enough. I think that’s enough.

What I’m Growing: I’m very late this year, but I finally put some basil seeds in some containers out on our back deck, and I’m out there six or seven times a day looking for signs of growth. I want pesto. In the yard, some chard has started to pop up, and the little leaves are so pretty, so promising.

It probably says something about my priorities that the flower seeds were the first I planted in our community-garden plot: zinnia, cosmos, poppies, sunflowers. I’m longing for beauty. Fozzie patiently stood watch as I planted Chinese greens and potatoes too. The dastardly Colorado potato beetles were devastating last season, and the Interwebs suggested waiting until later in the growing season to plant. But my seed potatoes have been sprouting, so I put a bunch in, and we’ll hope for the best.

How is your growing season going? Are you planting anything new? I’d love to know.

What I’m Reading: The Guardian ran an unexpectedly stirring photo essay the other day featuring the work of the photographer Herman Ellis Dyal. After many years away, Dyal returned to Riverside Church, the congregation in which he was reared in San Antonio, Texas. He reacquainted himself with the church’s people, and he visited and photographed the many empty rooms in the shrinking church. “Spending time in the church on weekdays, wandering and taking pictures in the darkened and empty church, I realize that I’m searching for something beyond photographs,” he writes in his book, The Things Not Seen Are Eternal. “Or perhaps I’m trying to somehow see through the photographs to something else. But I’m brushing up against a veil I can’t get past—cut off from the mystery. I long for a bush going up in flames. I long for my great cloud of witnesses, who may be in one of these rooms, if I just keep looking.”

Wired published an interview with Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, also a Michigan resident! He’s an intriguing character. I am with him in his convictions that there are some things a free market can’t—won’t—fix. I agree with him, too, that we get to redefine masculinity. I’m still pondering his spiritual perspective on travel, infrastructure, and transportation; “the conversion of Saint Paul happens on the road,” he says. And especially as a travel writer who often explores spiritual themes, I’m wondering about his argument that “we are all nearer to our spiritual potential when we’re on the move. Something about movement, something about travel, pulls us out of the routines that numb us to who we are, to what we’re doing, to everything from our relationships with each other to our relationships with God.”

Another part of the conversation that gave me great pause. “Your worth as a person,” he said, “depends in no small measure on how you make yourself useful to those who have the least power and the least means.” I get what he’s trying to say. I applaud any sense that one’s privilege should be deployed in the service of those who don’t have it. Yet according to my theological convictions, one’s worth as a person depends entirely on one’s belovedness to God. Out of gratitude for God’s love and grace, yes, we ought to love and to serve. But I struggle with the idea that human worth is contingent on any kind of productivity.

I’m grateful for all of the thoughtful, kind, openhearted emails and comments I received in response to last week’s letter about my conflicted feelings during Asian American/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Heritage Month. Hearing from and being in conversation with you is truly one of the best parts of this work. Remember that you can always email me at makebelievefarmer@gmail.com. This week, I’m curious: Where do you live, what brought you there, and, if you love living there, why? And what do you do to create your own sense of home and community?

I’ll be preaching at the First Baptist Church of the City of Washington, D.C., this Sunday morning, May 21st. We’ll be working with the Ascension texts from Luke and Acts. Would love to see you there if you’re in or around D.C.—or join us for worship online at 11 a.m. ET.

That’s all for this week. As ever, I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

With gratitude,

Jeff

Thank you for this piece. As always, absolutely wonderful. I appreciated the link to the pictorial essay that appeared in the Guardian. The photos were stunning. I am guessing many churches have these kinds of unused spaces on their campuses.

I'm encouraged by how my Episcopal Church has evolved to changing times. We have a large campus with several different buildings. Many years ago, our parish rectory was converted to classroom and lab space for the growing day school. Times changed, and the school eventually closed. Recently, we've renovated the marvelous space back to its original purpose: housing. Our new neighbors just moved in. In its new form, it's a sober living home for women in our community who need a fresh start, a place where their children can live with them as they work through recovery. Former classroom space on our campus is now occupied by a thriving preschool operated by an outside organization. There's also a drumming school! We have a large apartment that's being rented to a family at below market rate, something that's welcome in a community with scant affordable housing, and very little housing inventory overall. I live about two blocks from my church, and I love seeing (and hearing!) these neighbors on my daily walks.

Our ED Los Angeles Bishop - John Taylor - is spearheading a movement in consider how we're using underused church space in our diocese, and how we might benefit our communities by shifting use to affordable housing and more. We've just hired a "czar" to work in our diocese to help our parishes effect change around use of our space.

These changing times invite us to imagine new possibilities.

Hi Jeff, I appreciate your thoughts/feelings about living in a place, loving it, making a life in it, but not feeling “home.” I moved to SoCal six years ago from my native Ohio, and I often feel those same feelings. Am I an Ohioan or a Californian? I feel as if we were “sent” here, so rather than worry about labels, I guess I should try to create peace, love, and beauty wherever I am and know that’s enough. Thx for the reminder!