Christmastide II

Thursday, January 5

Grand Rapids, Mich.

On the fourth day of 2023, dear reader, I made fried rice.

In these gray, cold days of winter, I’m contemplating things that bring warmth and comfort, especially foods that both remind us of past encouragement and point us to the promised good still to come. Surely you, too, can summon memories—of something you’ve eaten that fed you not only pleasure but also a sense of possibility; something that tells a story beyond your own; something that stirred joy, perhaps, which is to say bitter as well as sweet.

In her recent book Salty: Lessons on Eating, Drinking, and Living from Revolutionary Women, the cultural critic and author Alissa Wilkinson imagines a dinner party with nine tremendous humans. I especially loved her reflection on the celebrated chef Edna Lewis, particularly this part:

Memories of cooking at the elbows of her relatives stuck with Lewis, as did those of gathering to eat the fruits of their labor, along with the emotions that went with them. The excitement of butchering pigs in the fall, then blowing their bladders up like balloons with straws and hanging them to dry out for use as Christmas decorations... The happiness of seeing far-flung relatives come home for feasts. The bone-weary gladness that comes with a long day spent in the kitchen or the fields, knowing that the fruits of your labor are yours, and no one else’s. These were the memories that lodged themselves in Lewis’s brain.

Maybe the memories were etched onto Lewis’s palate, much as yours might be too. Certainly mine are.

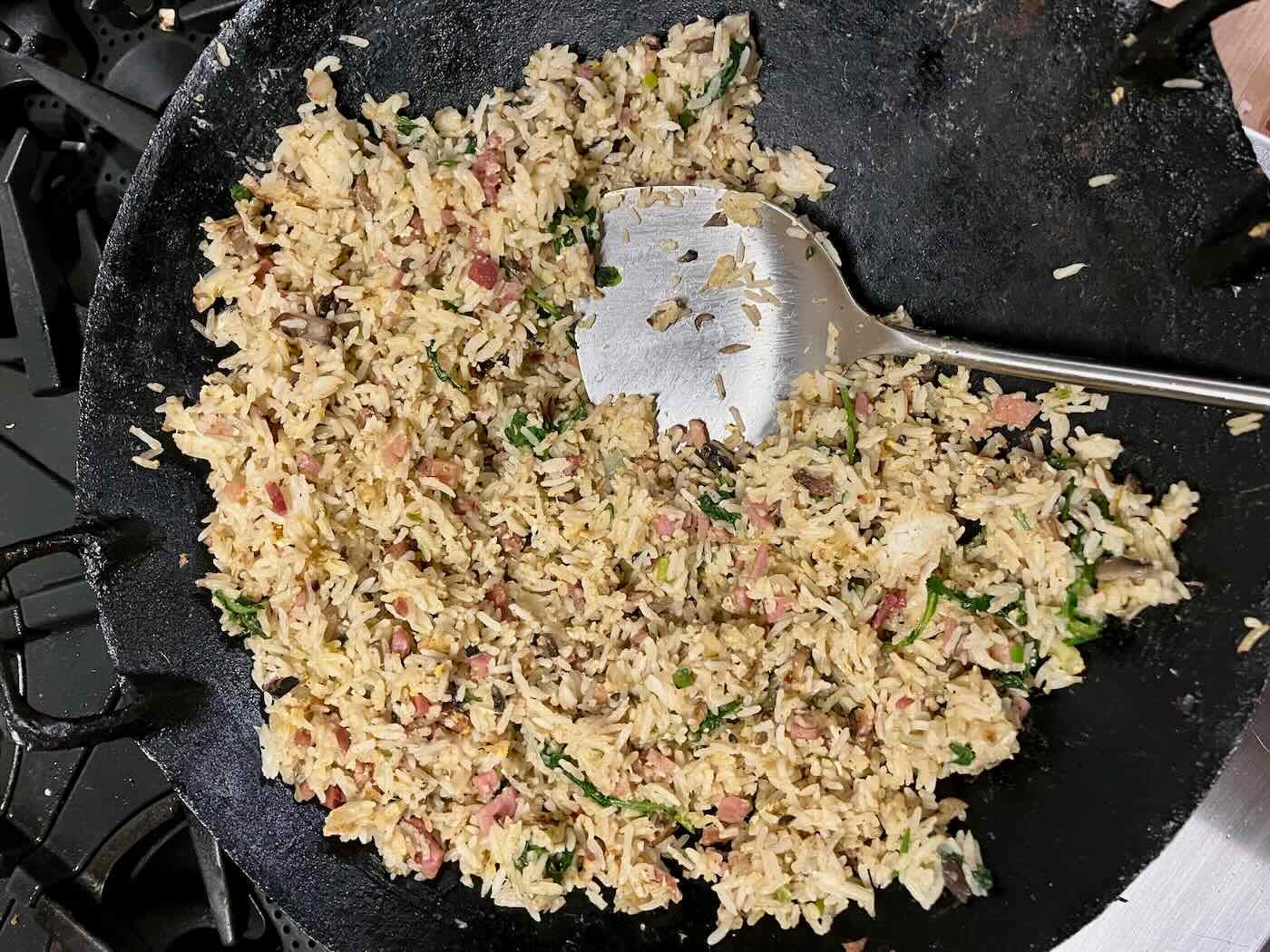

Which is why I am thinking, as I so often do, about fried rice. Last night’s version: honey-baked ham, left over from our New Year’s dinner; baby kale; mushrooms; onions; garlic; scallions.

I’ve written to you before about fried rice and how I make it. But I don’t think I’ve ever told you the story of exactly why this dish matters so much to me. It isn’t really one story so much as a collection of them.

***

Summer 1988, Berkeley, California: We’d moved across the country two years before, leaving behind all our family. For the first time, I lived in a place where there weren’t many faces that looked like mine and the weight of being different.

Even now, it only takes a millisecond to be transported back to the classrooms and hallways of Wildwood Elementary School, which I came to hate. Rick, Kristin, Mac: I can still tell you my bullies’ names and exactly what they did, exactly what they said—especially Mac. Where the other two were just generically mean, he was specifically wicked and racist and cruel.

Each summer, my sister and I returned to California, as if migratory birds. We stayed with our paternal grandparents, becoming by far the youngest residents in an apartment building reserved for old people and sleeping on the pullout couch in the living room of their one-bedroom unit. There, I felt safe again.

In my grandparents’ apartment, I always sat on a stool wedged into the corner of the living room, which was also the dining room. There, I watched my grandmother in the kitchen—wielding her heavy cleaver, stirring with her wok turner, making me fried rice. My sister hated green onions. I loved them. So my fried rice always came with extra green onions—and a reminder that, in Cantonese, the word for green onion, 蔥 (“choong”), is homophonous with the first character in the word for intelligent, 聰明 (“choong ming”).

I don’t know that the green onions made me any smarter. But they and the fried rice—they did make me feel safe, and they did make me feel loved.

***

After school, 1995, Miami: I was graduating from high school, and my grandmother would be there. We’d bought her plane ticket six months before. But then we got a call: She was in the hospital. She’d had a stroke. We flew westward immediately.

Grandma looked so peaceful in the hospital bed. I held her hand and begged her not to leave me—not yet, because we had plans, because we already had her plane ticket. Then she waited until all the family had left for the night. An hour or so later, someone from the hospital called to say that she had died.

Grief is weird. Shortly after we returned to Florida from the funeral, I had to make up a calculus test that I’d missed while we were away. I hated calculus, my brain struggled to process calculus, and even at the best of times, I could barely force myself to study calculus. For the first time in recorded history, much to my surprise as well as my math teacher’s, I aced a calculus test.

Such was my sorrow that, for once, I didn’t even care about the A. It felt as if I were just moving through the motions of life, but sometimes that’s what you do when you’re sad—you do the things until you can feel other emotions again.

I don’t know how many batches of fried rice I made following my grandma’s death. But it was what I knew how to do. Many afternoons, while my mom was still at work, fried rice was my go-to afterschool snack. We always had leftover rice in the fridge. And eggs. And leftover meat of some kind. And of course green onions.

***

July 4, 2004, London: Friends had come for Sunday lunch. I can’t remember what I cooked; it might have been tagine, because I’d brought back a couple of clay tagine pots from Morocco and I was in a tagine phase—lamb and prunes, often.

What’s clearer in my memory is that, as with the best Sunday lunches, 1 became 2, and then 2 became 3, and 3 became 5. We might be talking about the time or the bottles of wine. Both, really: Everyone was still there—pretty full, pretty drunk, pretty happy.

That was the summer of the European Championships, and the final kicked off at 7:45 that evening: Portugal v. Greece. I didn’t care for either team, except that my dislike of Portugal—diffident, arrogant—was already well formed. They’d defeated England during the quarters—penalty kicks, of course. Anyway, Greece had only qualified once before for the Euros and once for the World Cup. They were certainly the underdogs, and as they pushed through the group stage, then the quarters, then the semis, they became Σταχτοπούτα—somehow that’s Greek, I’m told, for Cinderella.

“I’m hungry,” someone said as halftime neared. So I went into the kitchen and dug around in the fridge. Leftover rice. And eggs. And leftover meat of some kind. And of course green onions.

I remember that, after we’d each had a big bowl of fried rice, my friend Jumana slid off the couch onto the floor. “I’m so full,” she said, holding her belly. “It hurts.”

She paused, and then she said: “Is there any more?”

***

October 2018, Brooklyn: I’d been in Dallas for work, and I’d tucked some leftover brisket, ribs, and sausage into my backpack to take back to New York.

As the backpack passed through the airport scanner, the TSA agent’s eyes widened. He surveilled the line for the bag’s owner. By the looks of things, he was Chinese American too. When he saw me, I waved. Immediately, his face softened, and he smiled, nodded his approval, and gave me a thumbs-up, as if to say, Yes, this is how our people travel.

The next night, I took out the brisket, and I made fried rice. The smokiness of the meat complemented the umami of the soy, and the onions and scallions gently cut the fattiness of the brisket. Why hadn’t I thought of this before? It was us in a dish: Tristan’s Texas and my Hong Kong.

This would be the perfect story if I told you that Tristan had savored this expression of our marital love. He did not! He was out of town. I scarfed down that entire batch of brisket fried rice myself. Whatever. It was delicious. And let’s call it practice: The next time we had leftover brisket, I made him some too.

***

In a world fraught with struggle and a life burdened by stress, meals should be more than mere nutrition-delivery systems. Of course every dinner can’t be a feast. Sometimes you just have to eat. Sometimes you just have to get the food on the table.

But now and then? I wish for something more.

In the introduction to Salty, Wilkinson writes that, in each of the nine women she profiles, in each of the people she has gathered around her literary table, “I see grace breaking through, enabling them to face an often frightening world and give courage to their readers, to their audiences, to their communities.”

Isn’t that what a good meal can and should be and do? Isn’t that what ought to happen when we cook and when we feed? I wish that for me, and I want that for you.

May you know a dish that tastes like safety.

May you experience meals that feel like grace.

May you enjoy many a supper that summons you back to love.

What do you cook, dear reader, that brings back cherished memories? What do you wish you could eat again, if only someone could prepare that dish for you? I’d love to know.

There are still two more days of Christmastide, so it’s not too late for me to commend to you the Christmas service from Crosspointe, my church in North Carolina. We filmed early last month while I was down there to preach. I think it’s just beautifully, movingly done, and I think the snippet of Scripture that pastor Jonathan Bow preaches on—“the Magi went home by another route”—offers timeless inspiration to those of us who have had to find a different way. (I have a short segment in which I tell a story about fried rice—on brand, right?)

That’s all for this week. The sun isn’t up yet here in Michigan, but Fozzie is, and I can tell by his face that he’s wondering why we aren’t out for a walk.

I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

With all my best wishes for good eating,

Jeff

This is beautiful, Jeff. Thank you.

When I was growing up in Colorado, we lived days away from family in Texas. My “adopted” grandparents taught us to fish (and cook) the trout from the river nearby. The best were smaller fish we called “brook” trout (not sure if that is officially what they are called)…so sweet and tender. Mr Parker would bread them with cornmeal and fry them outside, while inside, Mrs. Parker would make baked beans, hot potato salad, sweet tea, and chocolate pie. Same sides every time unless we were cooking them right beside the river and then just potato chips and white bread would suffice. It is the meal of my childhood. Mrs. Parker passed away a few years ago, Mr. Parker moved to be with family, and it’s been years since I moved on, but if I could have one single meal right now, it would be that particular meal with those particular people. Thanks for reminding me!!