When Family Trips Are Not Vacations

Some fragmented thoughts on Disneyland, the endurance of difficult love, garlic, the plight of the Chinese Uyghurs, and a whale that might (or might not) be lonely

Thursday, July 22

35,000 feet above Colorado

Greetings, dear reader.

I’m starting this letter as I fly back east from California after taking my nephews to Disneyland.

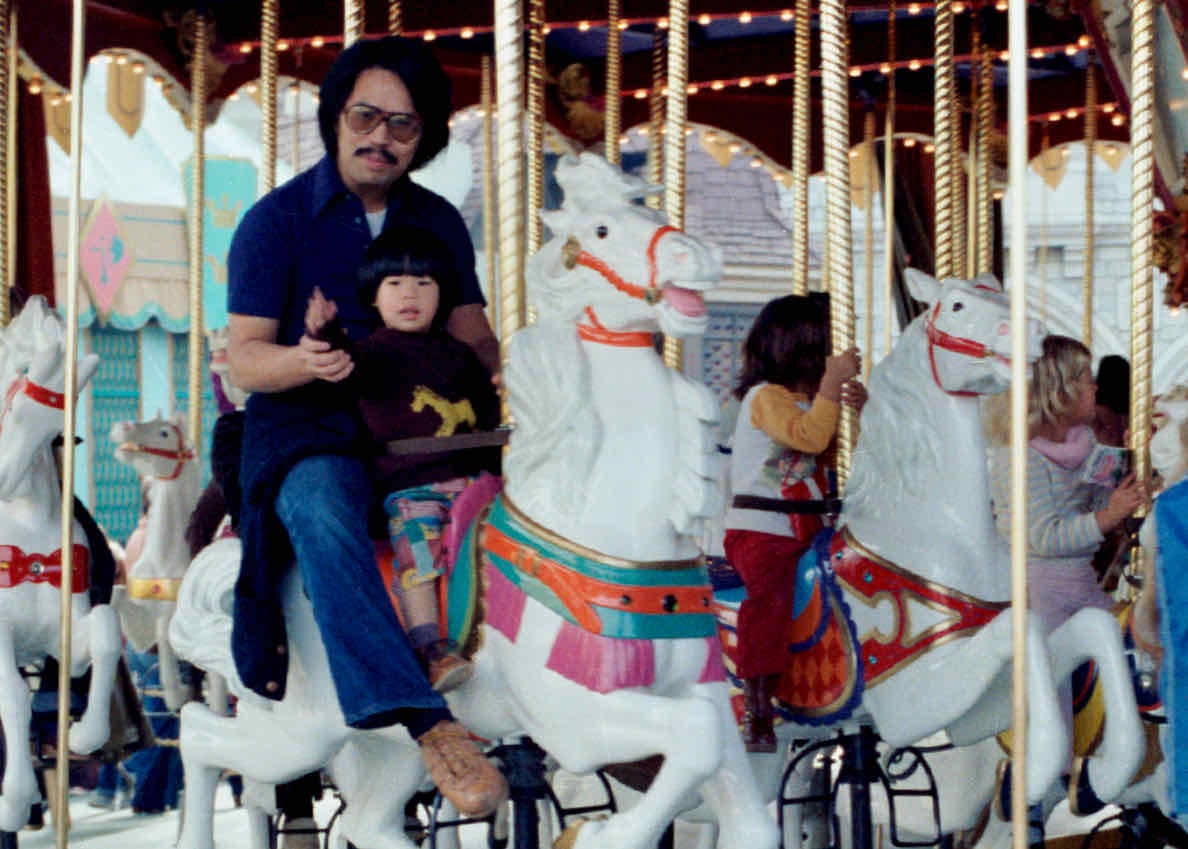

Here’s a picture from my first trip to Disneyland.

I think this was my first trip out of the Bay Area, where I spent much of my childhood. I have no memory of the trip, but this photo tells me the story of a dutiful, persistent young dad. Then in his early 30s, he had recently finished college thanks to the G.I. Bill. When he first arrived in the U.S., he delivered pizzas and drove a taxi. Now he was slowly working his way into the professional class, allowing him small luxuries like a family visit to Disneyland. Also, I wish I had an adult version of that giraffe sweater.

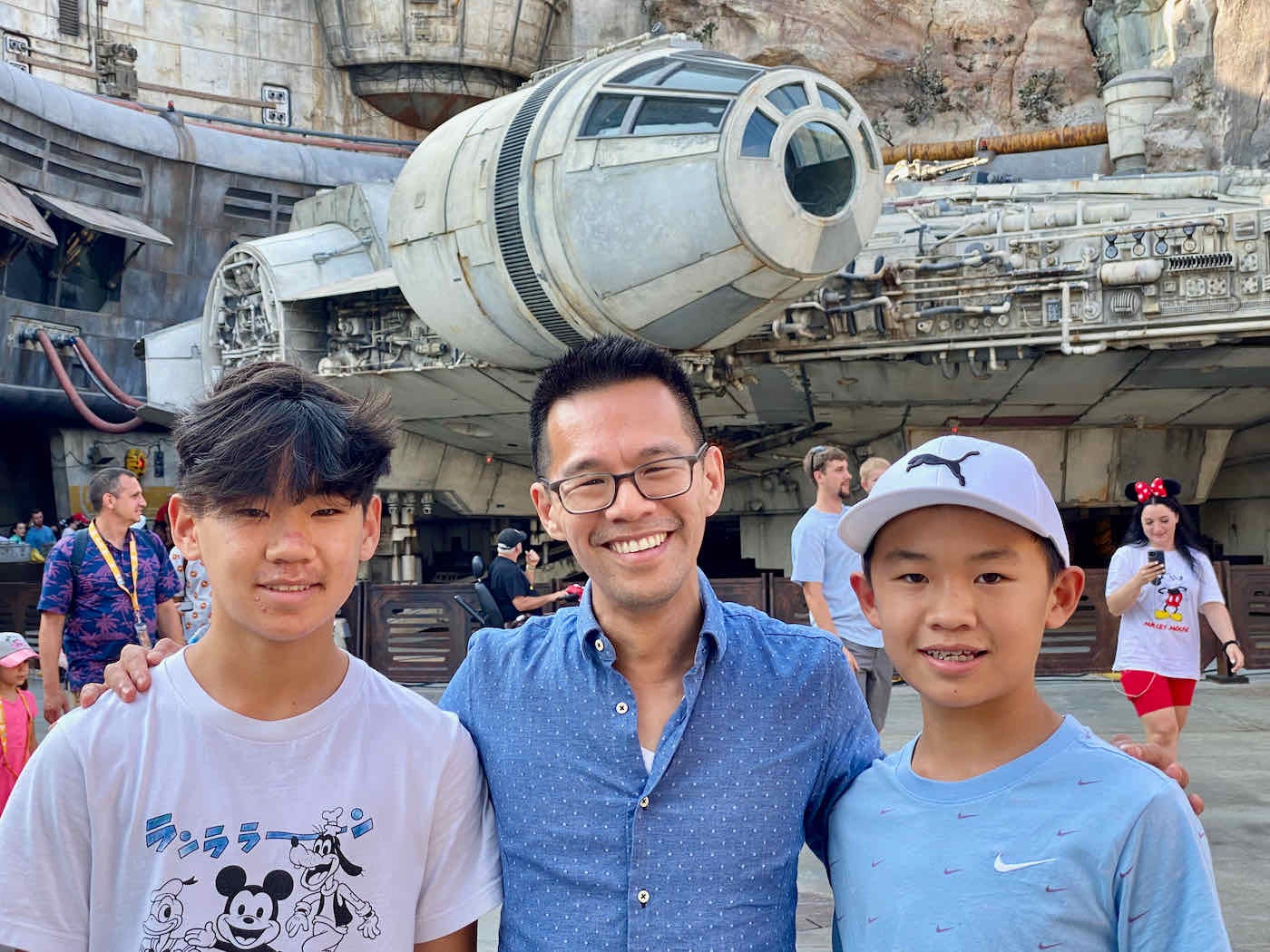

A few decades later, that same man is a comfortably retired grandfather, and he returned to Disneyland with his wife, his son, and two of his grandsons. We walked miles and miles. We ate overpriced theme-park food. And while I grumbled a bit about how expensive the tickets were, my dad, stereotypically Chinese and therefore frugal yet generous, never said a word about the cost. I think he was just glad to make this trip with another generation of progeny.

Walt Disney once said that he created Disneyland to be a place where both adults and children could have fun together. But “fun” is not really a word that I use much in my daily life, and anyway, it means different things to different people. What at Disneyland did my dad consider “fun”? Unclear. And I’d hoped to get a picture with my cartoon soulmate, Eeyore, who was nowhere to be found; maybe he’s not the most popular with crowds. Anyway, I settled for one with Sadness, from Inside Out—painfully on brand, I know. Does that count as “fun”?

Anyway, this trip was really for my nephews. So I delighted in their enthusiasm as they rode the Incredicoaster, a roller coaster inspired by the movie The Incredibles, four times—I sat on a bench and waited with my parents—and even happily endured their laughter as I surrendered any remaining cool-uncle cred by refusing to join them on Guardians of the Galaxy—Mission: BREAKOUT! Thirteen-story free fall? That’ll be a no from me. I’m not a total killjoy, though: I went on Splash Mountain. I liked Radiator Springs Racers, which goes a little bit fast. And we all loved Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance, a beautifully immersive, truly transporting storytelling experience as well as an outstanding ride.

Alas my judgment failed me when it came to the deviously named Pixar Pal-A-Round, an innocent-looking Ferris wheel adorned with Mickey Mouse’s smiling face. This monstrosity has gondolas that swing wildly and roll down tracks as the Ferris wheel makes its rounds. The English language doesn’t have words adequate to describe the horrors. There are no seatbelts. There are no safety bars. There was nothing for my desperate hands to hold onto. All I could do was close my eyes and surrender to the unexpected sudden revival of my prayer life. Turns out all I needed was to be trapped in a cage as it gyrated over Southern California. Never again.

There might be a scientific explanation for our different approaches to fun. Though the mind largely remains a mystery, scientists have begun to explore how people respond divergently to thrill rides. It might have much to do with brain chemistry, including how we process dopamine rushes and whether we experience the stress of a ride as good stress or bad.

When I asked the elder one, Ryan, which ride was the worst, he quickly answered, “The Inside Out one.” Inspired by the Pixar movie, that ride’s full name is the Inside Out Emotional Whirlwind. It’s kind of like the Dumbo ride, only with different characters: You ride up and down, round and round. It’s all gentle and pleasant until you register the soundtrack, which consists of characters from the movie saying things to you like, “An emotional whirlwind gets you nowhere.” I highly recommend it to anyone who feels the need to be emotionally attacked at a theme park.

In the aftermath of that emotional attack, I noticed that my reaction to the Inside Out Emotional Whirlwind was different from Ryan’s: curiosity, bemusement, some discomfort. I did not hate it. Where other rides sought to deliver escapism and thrill—I can recognize that even that damn Ferris wheel had good intentions, if questionable impact—the Emotional Whirlwind wasn’t much fun. But it was the ride that has stuck in my mind, because it is so different than all the others.

Perhaps the uncomfortable reality of the Inside Out Emotional Whirlwind was precisely that it dealt in reality when I’d been hoping for a purer form of escapism. Perhaps its hidden gift was that it reminded me that, even at Disneyland, we can’t entirely escape our present circumstances—and there can be blessing in attentiveness to what is, rather than what we want it to be.

The film Inside Out was informed in part by “Reason and Emotion,” a short wartime propaganda film that Walt Disney Studios made in 1943. “Reason and Emotion,” which was nominated for Best Animated Short at that year’s Oscars, posits that a “ceaseless battle for mastery” is constantly being fought within each human between our ability to think (reason) and our ability to feel (emotion). It depicts emotion as something to be subordinated to reason, and it holds up Hitler, “a master rabble-rouser [who] destroyed reason,” as one who both thrived on his own untamed emotion, which manifested in fear and pride and hate, and exploited that of the German people.

Inside Out is significantly more nuanced than “Reason and Emotion.” It seeks to understand emotion rather than to tame it. The movie acknowledges the entire chorus of emotions—joy, sadness, fear, anger, and disgust—as potentially helpful and useful but also, and if out of balance, possibly harmful and even dangerous. (Early on in the film’s development, the cast of collaborators was more diverse, including envy, gloom, shame, pride, hope, and embarrassment, but they got left on the cutting-room floor.)

Obviously, both films vastly oversimplify humanity’s complicated internal terrain, as is the Inside Out ride. So even though overthinking is my forte, I don’t want to do too much of it. But I do have one question: In the internal ecosystems of both these films as well as the ride, where is the place of the force—a word I choose consciously, because I’m not sure whether it’s an emotion or a feeling or a manifestation of reason or a mix of these and more—called love? Where is it? Where is love?

For many, if not most, of us, family trips are not vacations. I knew that this trip, sprinkled with Disney’s pixie dust as it was, would be stressful; question is, good stress or bad? Whatever the case, love manifesting as duty compelled me to make the plans and pack my bags and head to California. Love manifesting as self-sacrifice urged my dad to devote these days to wandering around the theme park with us, because he, a huge golf fan, undoubtedly would have much rather been watching the Open Championship on TV. Love manifesting as the willing acceptance of physical discomfort convinced my mom to come along too, given her strong dislike of hot weather and her affection for air-conditioning. Love manifesting as words not spoken, as irritation recognized and tamped down, was undoubtedly part of the Disneyland experience for every one of us; we hadn’t seen one another in nearly two years, so we were a bit out of practice with the restraint often necessary to be together graciously, but still we all tried our loving best.

Love is what I see in the man who carried his young son on his shoulders and held him on the carousel, the same man who now, in his mid-70s, accompanies his grandson for miles and miles along theme-park pathways. Love is what I see in the mustache that has turned gray and in the legs that, though still striding confidently, tire more quickly than they used to; sometimes, he needs to sit and rest. Love endures, though his son’s life has not unfolded the way he had hoped it would and though his grandsons might make choices that he can’t always understand. Love endures, though each of the people on this trip has their distinct worries, their competing convictions, their divergent theologies, as well as their mutual longing for respect and approval.

Through it all, there is love—a difficult love, a love that tolerates when it can’t celebrate, a love that says in presence what it can’t in words, a love that still insists on showing up. Perhaps attentiveness to that love, as imperfect as it might be, is enough, because it’s rooted in a love beyond them—a love that comes from God’s own self. That love is a miracle. That love must be our reality. That love is our hope.

What I’m Growing: I am back in Grand Rapids now, and yesterday, I harvested my first-ever garlic crop. What a tremendous difference between the cloves that were planted in the pretty good soil in our little plot in the backyard—big, full bulbs—and the ones that were planted in the poor soil on the side of the house—real garlic, yes, but miniature versions. Guess I harvested a sermon illustration along with the garlic! Anyway, it’s all now hanging down in the basement to cure for a month or so, but Tristan is already imagining what we might cook with our first homegrown garlic.

What I’m Reading: The Atlantic last week published a series of articles on what China is doing to its Uyghur minority—a five-part, firsthand account by the acclaimed Uyghur poet Tahir Hamut Izgil. It’s long, and it is heart-wrenching; I had to pause multiple times to gather myself. The series documents how the Chinese government has forced more than 1 million people into concentration camps, forcibly sterilized Uyghur women, cultivated fear, and methodically undermined an entire culture. “While the system of state terror in Xinjiang is orchestrated by an inhuman bureaucracy, the individuals running that system—and those crushed by that system—are human in full,” the American academic Joshua L. Freeman, who studies the Chinese borderlands, writes in his introduction to the piece. This system is operating well beyond Xinjiang, including in my beloved Hong Kong, where China is steadily dismantling the last remaining vestiges of free thought and democracy. Please don’t turn away. Lives and cultures are being destroyed.

What I’m Watching: Beginning in the late 1980s, marine biologists began detecting an unusual whale song different from any other. They came to believe that a single whale was singing at a frequency beyond the ranges used by other whales—52 hertz, like a low note from a tuba but much higher than your typical blue or fin whale. In the years since, people have speculated that this was a call without a response—and that 52, as some came to call the creature, must be lonely.

A new documentary, The Loneliest Whale, chronicles the filmmaker Joshua Zeman’s quest to find 52. He wonders whether 52 really is lonely. Are we projecting emotion onto a whale, or might it really be lacking connection?

I found this earnest documentary thoughtful and moving. There’s gorgeous footage of magnificent whales. And the film draws necessary attention to the sobering consequences of human activity throughout the seas: the incessant groans, grumbles, and whirs of ships crisscrossing the globe as well as the percussive pounding of oil and gas rigs drilling for fuel, all of which disrupt the communications of these tremendous beings. If you watch, stay on through the credits for a surprising epilogue.

I want to underline a phrase in my comments above: “a love that tolerates when it can’t celebrate.” I know that will grate on some people, and many will find the idea challenging, but I stand by it. It’s a reality of our existence in a world of disagreement and diversity. Tolerance is often underrated, even disdained (if you’re into philosophy, I commend to you the book Tolerance among the Virtues, by the Christian ethicist John Bowlin, who was one of my seminary professors). I think it’s unfairly maligned, because it can represent a kind of difficult love that is both laudable and beautiful. And it often draws on and points to a greater love—a divine love. Have you, in your own life, experienced such unlikely love or sought to cultivate it? Do you find my framing of such love as objectionable or somehow wrong? What questions does it stir up in you? Leave a comment and let’s discuss. I’d be glad to know what you think.

As always, I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I will try to write again soon.

Yours,

Jeff

I like your comments about tolerance--sometimes it helps us through a period of time so we can return to love and full acceptance. As the parent of children who have had struggles as they emerge into full adulthood, sometimes I've had to tolerate phases of life, just so we can get through the period of time into more acceptance. And I DO see the divine in that process

The word "tolerate" always makes me think about teaching diversity classes where we talk about what it's like to be tolerated as opposed to being loved or even respected. But sometimes tolerating someone or something is the best I can do in that place and time. I'm trying to think of tolerance as a place holder; a space in which I can store things while I work on a better understanding and maybe a change of heart and mind regarding each.