Words Matter

Some fragmented thoughts on Robert Alter's majestic translation of the Hebrew Bible, everybody's birthday, fried wonton, and a modern psalm for Lent

Lent I

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Hello, dear reader!

My first memory of hearing Scripture read aloud: I was four, maybe five. Morning devotions, just like every day, at my grandparents’ cottage in Berkeley, California. From the green-plaid-covered living-room couch, my grandmother voiced the words in her warbly Cantonese. Her left hand held her worn Chinese Bible, its cover cracked by time and frayed from use, while her right index finger followed each column of characters down each crinkly page, right to left.

At some point, I realized God’s voice was not that of an elderly Chinese woman. Moses, Elijah, and Jesus didn’t speak Cantonese. Grandma’s Bible wasn’t the only Bible. The words were originally Hebrew and Greek. This was a work in translation.

As I’ve aged, I’ve increasingly wondered: What did Scripture’s original authors intend? Why did they tell some stories and leave others to fade away? What were they trying to say, not to some audience unimaginable millennia later but in that first instance, in their particular time and place? What might we struggle to understand because we’re reading it in our language, not theirs?

Translating Scripture requires audacity; you have to believe you can uncover something in the text that others have not. It also calls for immense care. The questions that arise as we read Scripture aren’t merely academic. If it’s true that, as Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote, “words create worlds,” these words have tremendous power to shape how we perceive and interact with ourselves, one another, God, and all of God’s creation. Choose one word, and you might equip a reader with a bludgeon; choose another, and perhaps they’ll find themselves on a bridge.

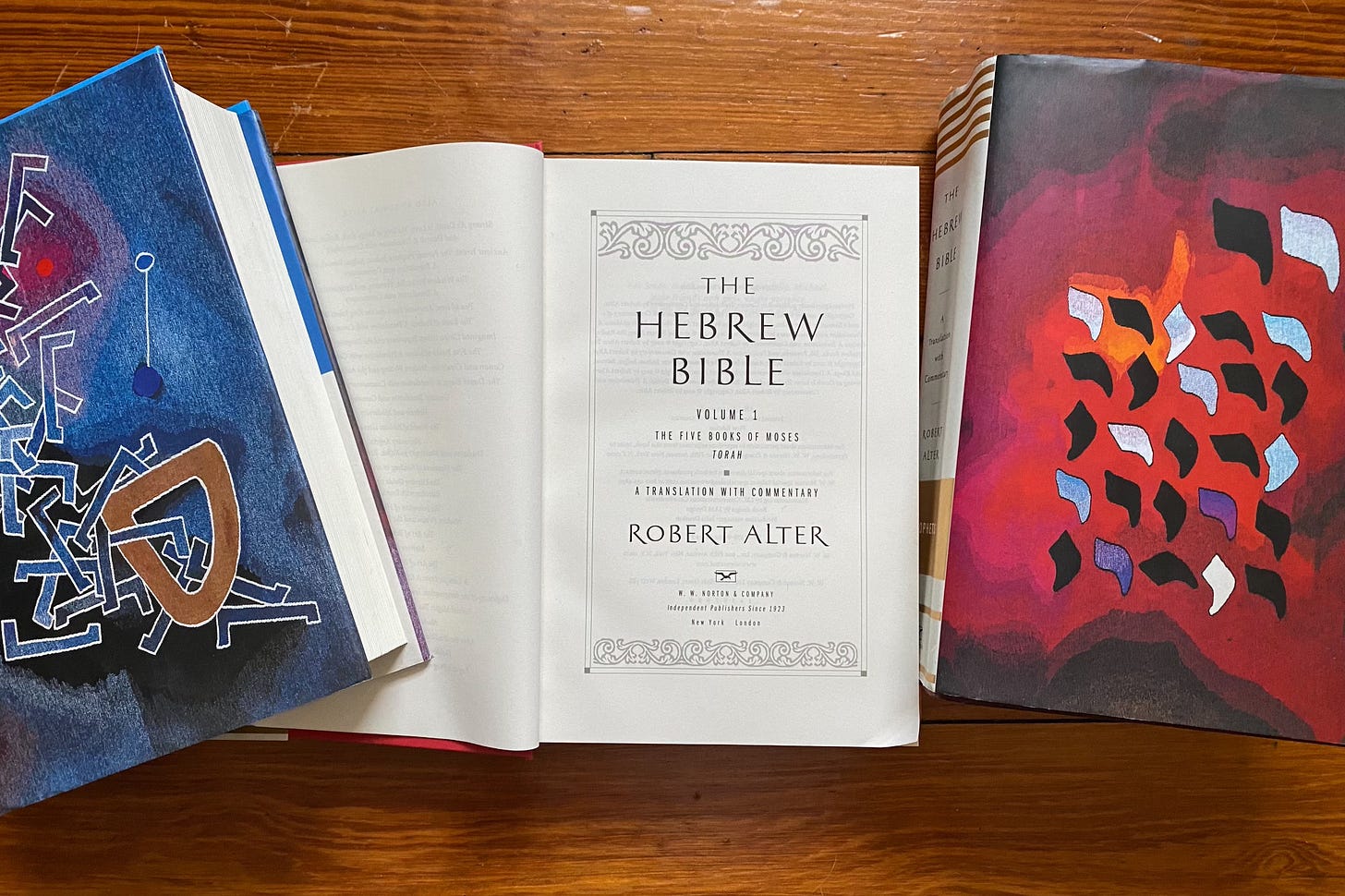

The version of the Hebrew Bible—what Jewish people call the Tanakh, what many Christians call the Old Testament—that has been most influential in my recent writing and preaching is Robert Alter’s translation, published in 2019. Armed with a scholarly scalpel honed over a lifetime of study, Alter, now 85, produced a work that I consult more than any other on my bookshelves. He has been called a biblical originalist, which suits him if you mean it in literary, not legal, terms: “I tried to get back to the feel of the Hebrew,” he said when I called him last week at his home near the campus of UC-Berkeley, where he has taught Hebrew and comparative literature since 1967. “To its concreteness. To its eloquent simplicity.”

In the Christian tradition, it’s rare for one person to translate the whole of Scripture. Most English translations were done by committee, including the NIV and the NRSV—at some cost and even insult to the reader. “They think that the only way to make Bible accessible or understandable to modern readers is to completely transpose it into modern terms and modern idioms. The effect of that is to make the Bible sound as though it were written yesterday,” Alter told me. “That diminishes some of the stylistic grandeur of the Hebrew.”

Alter cites Genesis 42, where, upon being reunited with his brothers, Joseph accuses them of spying on Egypt. The NIV renders his accusation: “You have come to see where our land is unprotected!” The NASB says: “You have come to look at the undefended parts of our land!” “That’s terrible,” Alter said. His version, which unveils the imagery in the Hebrew text, reads this way: “For the land’s nakedness you have come to see.” “The association with sexual taboos,” he explained, “is very powerful.”

His attention to the text’s layers points to his long career as a scholar of literature. His research interests have ranged widely. Among his first seven books are studies of picaresque novels, Henry Fielding, modern Jewish identity, and Stendhal. His eighth book, The Art of Biblical Narrative (1981), began his explorations of Hebrew Bible. He followed that withThe Art of Biblical Poetry (1985). In 1996, at an age when other people are trying to decide whether to start taking Social Security payments, Alter published his first translation of Scripture, starting, of course, at the beginning, with Genesis. In the end, his full translation took 24 years to complete.

His primary motive was literary. “For reasons we can’t fathom, these Hebrew writers working in the Iron Age, that community of people which was kind of the boondocks in many respects, when you compare it with the greatest empires to the east and south, produced writers of genius,” Alter said. He names Job as “the very pinnacle of Biblical poetry—some of the greatest poetry that has come out of the ancient Mediterranean world. No poem in any language I can read more powerfully expresses despair than Job’s death-wish poem in Chapter 3.” And he praises the best of the psalms as “deeply eloquent” works “that raise your spirits through their sheer beauty.”

This isn’t to say that he finds every part of Scripture equally inspiring. There’s Leviticus (“I can’t get all that excited about instructions for how you butcher animals for sacrifice”) and the first nine chapters of I Chronicles (“Nothing but a list of names. What can you do with that?). He’s also unsparing about what’s unoriginal, including some prophetic warnings (“boilerplate stuff”) as well as Psalm 119 (“pretty much a stringing together of set formulas—not really very interesting as poetry”).

Alter examines words and phrases as a gemologist might attend to a ruby. As our conversation continued, the geekery deepened. I asked if any word or phrase delighted him in Hebrew but lost texture in English. He thought for a long moment. “There is a phrase that occurs at the beginning of Job’s poetry, in the ‘death-wish poem,’ and then pops up again in a very different context, in the representation of the Leviathan [in Chapter 41]: ‘the eyelids of the dawn,’” he finally replied. “Which I think works well in English, but I’m not entirely sure. Again, modern translators have felt, Well, we have to make that clearer, so they say something like ‘the first gleaming of dawn.’”

While lovely, “the first gleaming” erases the embodied aspect of “the eyelids of the dawn”—and embodiment came up repeatedly as we talked. “An awful lot of biblical language is embodied,” he said. “The spirituality of Psalms is very resonant. All of us who read Psalms feel at times that it speaks to our own inner condition, whether we’re struggling with grief or in exultation. And it is an embodied spirituality. It speaks through metaphors of the body and feels that the Spirit is here, inhabiting the body.”

Body language seemed to give some translators pause, though, and Alter corrects the prudishness of recent English translations by restoring the Hebrew’s visceral bluntness. For instance, in the story of Abigail and David, from 1 Samuel 25, the NRSV quotes David as vowing not to “leave so much as one male” alive. That’s not what the Hebrew says. Incandescently angry at Abigail’s husband, Nabal, David harshly pledges not to let even “a single pisser against the wall” survive. “There’s a lot of vigor in the Hebrew that modern translators are afraid of,” Alter said. “They try to bleach it.”

Another example: In Genesis 21, after Abraham banishes Hagar and Ishmael, Alter said, Hagar “does something to her son under one of the bushes.” But what exactly? In the NRSV, she “cast” Ishmael under a bush; the NIV and ESV say she “put” him there; the NASB “left.” All so gentle! But again, that’s not what the Hebrew says.

“The verb is unambiguous,” Alter said. “The Hebrew actually says ‘flings.’” It’s the same word in Pharaoh’s death sentence on firstborn Hebrew sons: “Every child you shall fling in the Nile.” “All the modern translators say, A mother isn’t going to fling her child down. Presumably she didn’t fling him too hard,” he explained. “It was a bold choice on the part of the Hebrew writer. He understands this woman is absolutely desperate and understands her child is about to die, and in a paroxysm of maternal grief, she flings him down and runs away. Which you lose when you choose one of these pallid verbs.”

Alter didn’t always have a nuanced appreciation for Hebrew. He learned Hebrew because he had to, in preparation for his bar mitzvah. “I didn’t have much use for Hebrew school. I saw it mostly as wasted time,” he told me. After his bar mitzvah, for some still-mysterious reason, he registered when his community, in Albany, New York, offered a small class for boys. When he was 14, a new teacher arrived from London, armed with a PhD, a commitment to rigorous classical grammar, and enough youthful enthusiasm to persuade his young charges. “He was terrific,” Alter said. “He showed all kinds of connections between Hebrew and other Northwest Semitic languages. It was at that point that I really got into it and began to develop my love for Hebrew.”

Much of Alter’s work is akin to that of a skilled art conservator who strips centuries of accumulated grime and added paint and varnish from an ancient work. Translation is also interpretation—his extensive footnotes explain many of his choices—and many modern translators imposed post-biblical interpretations onto the text. Alter’s favorite example: Psalm 23:5, where the psalmist says to God, “You anoint my head with oil.” According to Alter, “the verb that’s used does not mean ‘anoint.’” Mashach, Hebrew for “anoint,” is a cognate of mashiach—messiah. “That verb and that action are used in only two contexts,” he said. “One is the consecration of the high priest and the other is for the confirmation in office of a new king.”

The verb in Psalm 23:5 isn’t mashach; it’s dashen. “That verb means something like ‘to make luxuriant.’ I couldn’t quite come up with an English equivalent, so I opted for something neutral: ‘You moisten my head with oil.’ The point is that it’s neither sacerdotal nor political nor messianic. It’s part of the good life,” Alter explained. “You rub good virgin olive oil onto your head, like in The Odyssey, when a stranger arrives from a journey, and they bathe him and they rub him with oil. But those translations introduce a whole post-biblical register of meaning that is kind of a messianic view.”

I understand the desire to read additional meaning into the text. Every reader comes with his own context, her own perspective, their own hope of being seen and known. And part of the Bible’s power derives from its ability to touch a wide audience—and, in some sense, to unite it. Alter has found great personal hope in Job, because of “the way the book wrestles so honestly with unjust suffering. That really speaks to me.” He also mentioned the psalms of lament in this regard. “Grief is a fundamental part of all our experience as human beings,” he said. “We’re all mortal. People whom we cling to dearly are at some point going to be taken away from us, or we ourselves may feel stricken.” The psalms of personal lament meet us there. “They give a voice, a very eloquent voice, to our grieving. We feel, Well, somebody else has gone through this.”

Yet note how he says, “Somebody else has gone through this,” not “This is about me.” Faithful reading ought to involve a particular kind of empathy that moves us not to imagine what we want the text to say or that the story somehow centers us but instead to discern what its original writers intended.

For Alter, ever the literary scholar, faithful translating was informed by a similar empathy, which demanded fidelity to the text and to a language that he loves. He’s also not shy about naming his limitations. “There are places where I couldn’t quite figure out an absolutely apt English equivalent, and I made a compromise, and some of those compromises might be slightly unfortunate,” he said. He tells his students that all translations, even published ones, are works in progress. “There are always ways here and there that you could make them better,” he said. “When you translate great works, unless you have delusions of grandeur, you should always have a sense of humility.”

Alter is now working on two other projects. One is an autobiography “about how I came to be the kind of writer that I am.” There’s an entire chapter about his wife, who recently passed away. “It includes our love story,” Alter said. “It was a great love story.” The other is a biography of the late Israeli scholar and author Amos Oz.

I suspect it will be his work on the Bible that leaves the greatest mark. The reach of the project has surprised Alter. He thought it would mainly draw “people who have a literary interest in the Bible and might want to get a better handle on it,” he said. His inbox has told a different story, bursting with notes from “people of faith—all different kinds of faith: a Presbyterian organist. An Episcopalian nun. A Modern Orthodox teenager,” Alter said. As he has considered why, he has realized: “You can’t really separate the literary from the spiritual in the Bible. I think that many readers seem to feel that my translation, which focuses so relentlessly on the literary vehicle of the Bible, brings them closer to what the biblical writers want to say to them spiritually. And I feel good about that.”

What I’m Cooking: Today is the seventh day of the Chinese New Year, known as 人日. People’s Day, a.k.a. “Everybody’s Birthday,” marks humanity’s creation. Historically, it wasn’t my people’s practice to mark individual birthdays; in our collectivist culture, everyone added a year to their ages on this day. In some parts of Chinese diaspora, particularly Southeast Asia, 人日 is celebrated by eating a raw-fish dish called 撈生, a distant cousin of the poke bowl. It’s not customary among Hong Kong people, but still, maybe I’ll use this as an excuse to ask Tristan if we can order sushi tonight.

We still have New Year leftovers in the fridge; I’m planning to have poached chicken over rice for lunch today. Someone asked for my fried wonton recipe. It’s pretty simple.

You want to get Hong Kong-style wonton wrappers, which are thin, from the Asian grocery store. Sometimes they come frozen; if so, just leave it on the kitchen counter for an hour and they should be good to go. The ones I use are “Twin Marquis” brand.

In a mixing bowl, combine a pound of ground pork (ground beef works too, if you don’t like pork, and vegetarians could use shiitake mushrooms); two or three slices of ginger, finely minced; a scallion, finely minced; 2 T of soy sauce; 2 T of Shaoxing wine (or sherry, or don’t worry about it if you don’t have either); 1 T of sesame oil; 1 t of white pepper (black is fine too); and half a teaspoon of salt. Mix well.

In a separate bowl, beat an egg; you’ll use that as the glue to seal your wontons.

In the center of a wonton wrapper, place about a teaspoon, maybe two of filling. (Too much, and the wonton will burst when frying. Too little and it’s all wrapper, no meat—but really, the fried wrappers are pretty delicious.) Dip your finger into the beaten egg and run it along two sides of the square wrapper. Fold the wrapper over the filling diagonally to make a triangle, and press the edges together to seal well.

When the wonton are all wrapped: In a small pot, heat three inches of oil (not olive, something neutral like canola or avocado) on the stove to 350 degrees. I usually don’t take the temperature; I just break off a tiny corner of wrapper and toss it in; if it floats and bubbles, the oil is ready, but if it sinks, it’s not. Don’t crowd the pot; I fry two or three at a time. They’re ready when golden—maybe 30-45 seconds on each side?

Good dipping sauces: Thai sweet-chili sauce (you can buy it in any Asian grocery). Or sriracha, with a touch of honey or maple syrup.

If you end up with extra filling, just stir-fry it in a pan. Tastes great over rice, with a fried egg on top.

What I’m Listening to: My friend Noah created a lovely lyric video for Sandra McCracken’s modern, winsome psalm, “Wisdom and Grace.” If you’re marking Lent, I commend it to you.

Well, that was a lot of words. Thanks for reading. Questions? Reactions? Thoughts? Know that I’m always glad to hear from you and to learn what’s on your heart.

I’m so glad we can stumble through all this together, and I’ll try to write again soon.

With gratitude and hope,

Jeff

I found this description of Alter's work so fascinating. Thanks, as always, for such an interesting and thought-provoking read.

What translation of bible do you use Jeff. ?thank you